David Butler, a recent graduate of the School of Pharmacy’s neurosciences doctoral program in pharmacology and toxicology, is one of five researchers in the country to be recognized as an outstanding young investigator by the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation.

The Foundation is the only public charity solely dedicated to accelerating the discovery and development of drugs to prevent, treat, and cure Alzheimer’s disease.

The young investigator award recognizes the achievements of talented young researchers and seeks to encourage the career development of the next generation of research scientists. Butler receives his award at a Washington, D.C. conference on Feb. 2.

While the award is a substantial achievement for any young researcher, in Butler’s case it is particularly significant. Butler, 49, conducted all of his laboratory tests and wrote all of his research reports using only one hand.

A cranial aneurysm and stroke 12 years ago left him without the functional use of his left hand, arm, and leg. But rather than be overwhelmed by his disability, he worked through it.

Building a Career Path

Once an industrial mechanic, Butler turned his talents and determination to academic study and research.

Besides his new doctoral degree, Butler holds a bachelor of arts degree in psychology from Salisbury University in Maryland and a master’s degree in neuroscience from the University of Hartford.

It has been quite a career path for the New Jersey native, who once was told his most probable occupation after his stroke would be as a shipping clerk.

“The key is not to focus on what you lost, but to build on what’s left,” Butler says. “I want people to realize there are support systems out there, and if you have any desire to improve your existing condition, there are resources available.”

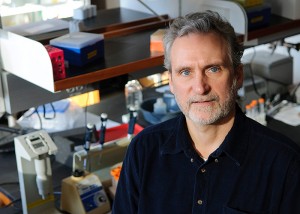

Butler credits his faculty advisor, Ben Bahr, an associate professor of pharmacology and neurotoxicology, with giving him a chance to prove himself.

Butler said it was not so much what Bahr did – although his help and guidance was clearly invaluable in the research – but what Bahr didn’t do that impressed him most.

“When he first met me, he saw I was disabled but didn’t hesitate for a minute,” Butler recalls. “He was amazing in that response. His confidence and courage really impressed me a lot and allowed me to challenge myself.”

Bahr recalls his first impression of Butler. “It was his enthusiasm,” he says. “I always look for a challenge. If he was looking for a challenge too, well, then I was all for it. But I told him, ‘We need to find a way for this to work.’”

With the help of Donna Korbel and her staff at the Center for Students with Disabilities, Butler and Bahr developed a plan that allowed undergraduate students to assist Butler with some of the more intricate testing procedures, while he closely supervised and monitored their every move.

Prototype Drug

Bahr and Butler, along with other researchers including Dennis Wright, an associate professor of medicinal chemistry, have spent the past three years developing a prototype drug they believe has the potential to improve the minds of Alzheimer’s patients whose thought processes often get lost in a tangled mass of excess protein deposits in the brain.

While other researchers have tried to develop drugs that reduce the production of the protein deposits at the core of Alzheimer’s disease, Bahr took a different route.

He developed a drug that makes lysosomes in brain cells more potent.

This causes them to act as aggressive garbage disposals of sorts inside nerve cells, flushing out the clogged masses of protein deposits that cloud the minds of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

The drug’s potential had already been demonstrated in cells in the lab, but Butler helped Bahr confirm its benefits in laboratory tests on mice.

Mice raised with genetic Alzheimer’s defects were able to find food hidden in a maze after being injected with Bahr’s drug, whereas similar mice not exposed to the drug often lost their way. The research results are currently under peer review.

“We changed experimental parameters at least 15 different times and Dave never lost confidence that something was going on here,” says Bahr. “Some people see strange data and if it happens twice, they never do it again. But Dave kept at it.”

Robert McCarthy, dean of the School of Pharmacy, says Butler has been an inspiration.

“The partnership between him and Ben represents the best we have here at UConn in terms of cutting-edge research and dedicated, hard-working individuals.”

Butler completed a doctoral thesis based on his Alzheimer’s research last fall and officially graduated in December. He will participate in commencement exercises in May. He has applied for a grant that would allow him to continue his research at UConn in the coming year.

“My interest is in fixing things,” Butler says. “I’m still a mechanic at heart. If there is a problem, I have to try and fix it. With Alzheimer’s, I knew the end point of the research was to make it better for someone with a horrible disease. Not only does Alzheimer’s affect individuals, it can last for 20 years and it destroys loved ones too.”