[flickr-gallery id=”72157627286622437″]

When a 200 year-old German playbook is damaged by centuries of use, handling, and storage, it can spell the demise of a priceless cultural and historical artifact.

“This playbook is falling apart, crumbling,” says Carole Dyal, the head conservator of the University Libraries’ Preservation Services program, as she gently picks up the 18th-century tome with a look of what can only be described as pain. “And, according to international records, we are the only library in the world with a copy of this text. As far as we know, another copy doesn’t exist. To lose it would be a tragedy.”

That this text had once been in general circulation within the library is shocking. It had survived storms, floods, two World Wars, Hitler’s book-burning campaign—and somehow made it across the Atlantic to the Archives and Special Collections located in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. And now it was on the verge of being lost forever.

“Thankfully,” says Dyal, allowing a smile to spread across her face, “we can fix this.”

Something old, something new

The University’s Preservation Services program is responsible for monitoring and repairing texts housed at both the Homer Babbidge Library and the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center.

This means that conservators handle books from general circulation as well as from archives and special collections, a fact that translates into a constant supply of work: at any one time, Preservation Services has around 3,000 titles checked out to it and in the process of being repaired. In recent years, the average number of books being repaired in-house each year has been between 8,000 and 9,000, with a turn-around time of about two months.

“You know, libraries are extraordinary things,” says Dyal, “and we want to see materials being used, because we believe in public access, and we believe in democracy, and we believe that we are a part of democracy because we are a part of education. But on the other hand you don’t want materials being destroyed. Here in Preservation Services we tend to see the dark side of library use.”

Spilled coffee, torn or missing pages, mishandling and misuse, and the general wear-and-tear of time all require their own techniques in order to be corrected—especially in the case of older texts. And that can lead to a pretty interesting work day for the staff of Preservation Services.

“One of the things I love about book conservation is the fact that we have super, super old equipment being used alongside super, super new equipment,” says Dyal, motioning to the lab behind her.

In many aspects, book conservation is a practice stemming back all the way to the advent of books, and many of the techniques and technologies still in use by book conservators today pay homage to that fact.

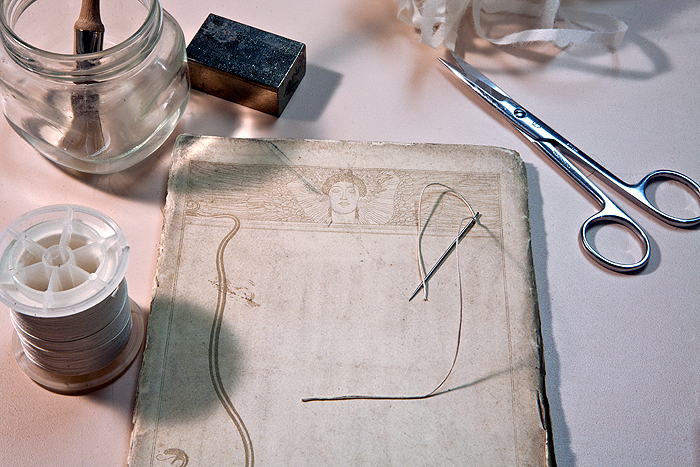

Throughout the lab are workbenches stocked with basic supplies needed to carry out book repair: Japanese paper to fix rips, wheat paste to adhere the Japanese paper to the page, cloth to create new covers.

These are all new twists on age-old practices, designed to be less invasive and less damaging in the long run to the books being repaired. But, despite slight swaps—the long fibers of Japanese paper for the short fibers of wood-pulp, reversible and chemically stable wheat paste for permanent and damaging glue—the techniques have remained the same.

And then there’s equipment that looks like it’s straight out of the history books—mallets and detailers and even human sized screw-presses that haven’t changed for centuries.

“At their best, those presses resemble something the Spanish Inquisition would have used to pry confessions out of victims,” says Dyal with a laugh. “But they get the job done—which is to force warped books back into shape—and there’s no reason to change them.”

And yet those presses sit side by side with some of the most state-of-the-art equipment you can get, like the suction table, which uses low suction to hold delicate and crumbled papers in place while they are being worked on and which Dyal affectionately terms the “alien incubator.” It can even be used as a humidifier, to restore moisture to books that have become so dry they would otherwise turn to dust. It is, Dyal attests, one of the most useful pieces of equipment in the lab.

“One of the things we have in Special Collections are Latin American newspapers from the 1800s and 1900s that are so completely dry and broken into bits that we call them cornflakes. They look like cornflakes,” says Dyal.

“Before we had this table to hold the bits in place it would take us hours—four or five or six hours—to get these piles of crumples into order. And can you imagine sneezing!”

Training the conservators of tomorrow

While Dyal is the head conservator in the Preservation Services program, alongside assistant conservator Xiaolin ‘Charlie’ Pei, a lot of the repair that goes on in-house is actually done by student workers.

Starting out with basic techniques and repairs, students move on to more complicated procedures as they gain experience. And, while Dyal and Pei may be the people working on the rare and valuable books from Archives and Special Collections that require special expertise to repair, some of the students who work in the program get so good at the job that they choose to pursue it professionally.

“I’ve had five or six students go on to professionalize within the field,” says Dyal. “One is now the rare books conservator at Princeton. One is the collections conservator at the New York Public Library. One is working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Another is the collections conservator at Berkeley. They fill a very important need in our society.”

Motioning once more to the German playbook from 1802, Dyal explains that it was actually a student worker who first discovered the value of the texts, which were a part of a large donation to the University in the first half of the 20th century. After spending hours scouring international databases, this student slowly came to realize that the copies available in Storrs were the only copies known to exist.

Says Dyal, “To lose these texts when we have the ability to save them would be unforgiveable.”