In Hot Topics posts, UConn experts comment on current events and issues unfolding in the news.

The recent arrest of Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky and the dismissal of Syracuse assistant basketball coach Bernie Fine following allegations that they sexually abused young boys has some people questioning whether existing laws for the mandated reporting of suspected child abuse need to change.

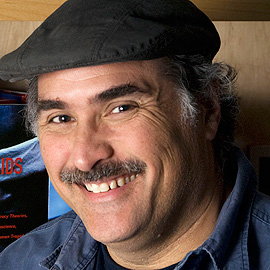

Seth Kalichman, a social psychology professor with UConn’s Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention (CHIP) and author of Mandated Reporting of Suspected Child Abuse: Ethics, Law & Policy, weighs in on the effectiveness of mandated reporting laws and what factors may cause some people to be hesitant to report their suspicions of child abuse or neglect.

Q: Mandated reporting laws for suspected child abuse vary among states; 18 states currently mandate anyone who suspects child abuse to report it. But other states, including Connecticut, have established a selective list of individuals – mostly professionals who work directly with children – as being mandated reporters. In the wake of recent child abuse allegations involving figures at prominent universities, should coaches, university professors, and other professionals in higher education be included as mandated reporters?

A: The answer is yes and no. It depends on whether or not that professor or coach has any interaction with kids. Jerry Sandusky is an example. UConn men’s basketball coach Jim Calhoun is also an example. During the academic year, university professors, as well as coaches like Sandusky and Calhoun, work with college students. But during the summer, they and their staff have these summer camps for such things as chemistry or basketball or soccer, and the focus of their job can change. Sandusky, for instance, had his organization, Second Mile, a Pennsylvania-based youth charity. During the summer, kids of all ages come to these camps for a variety of programs. In instances where minor children are being professionally served by professors, coaches, or other University employees, those professionals should be included as mandated reporters. College professors are functionally teachers in this capacity, and teachers are included on the list. If they’re working with children, they’re mandated reporters. There are states now that require that everyone be a mandated reporter. I think you’re going to see more of that. In the 60’s, pediatricians and emergency room physicians were the only mandated reporters. What’s happened over the decades since then is a broadening of the laws. In most states, there’s a long list of professionals. Don’t be too surprised if college professors and coaches are included in the list explicitly within the next year.

Q: Due to the wide differences between states’ mandatory reporting laws, is it time for the federal government to step in and pass a more comprehensive mandatory child abuse reporting law that all states must abide by?

A: No, and I’m not a big states’ rights guy. In this case, though, I think the federal government should stay out of it. The state laws have to take into consideration the resources of local police and child protective services. The reporting laws should be at a state level. There is a federal law that requires reporting: states can’t get federal funding for their child abuse prevention agencies if they don’t have a reporting law in place. The federal government doesn’t specify what the law has to say, it just says you have to have a law. And I think that’s probably what they should do at the federal level.

Q: The heightened awareness about reporting suspected child abuse brought on by these recent high-profile cases will likely increase the number of reports, and strain the resources of police and child welfare agencies that must investigate every claim. This could cause those agencies, potentially, to spend less time on or miss more serious cases of abuse. Is expanding mandatory reporting laws the best solution to preventing child abuse? Are there other alternatives that might be more successful than passing or expanding mandated reporter laws that are rarely enforced?

A: What will happen in the next year is a broadening of the statutes, and yet states will not increase resources going toward police and child protective services for these laws. The child protection system is basically broken; there’s going to be an influx in cases, with no real resources to support them. Strengthening the mandated reporting laws is not the answer. Mandatory reporting laws are not as important as intervening when families are dealing with such things as substance abuse and poverty, which can contribute directly to child abuse and neglect. I don’t think it’s an either/or situation. Mandated reporting laws are important. But I think what we need to do nationally is to think more about how we are and how we are not protecting children from abuse and neglect. There’s no reason to believe that child abuse is getting any less prevalent and any less common.

Q: There are laws that clearly outline the proper steps for reporting suspected child abuse. Yet, sometimes these steps are not followed. What sort of psychological barriers or other factors exist that might cause someone not to report suspected child abuse?

A: The laws are designed to remove a lot of those barriers. As far as reporting laws, if you file a report and it turns out not to be abuse, you’re protected from being sued unless it can be proven that you filed a report maliciously. Reporters are generally protected; their anonymity is generally protected. Some of the factors that may contribute to delays in filing a report are denial and institutional barriers. The notion of a graduate student blowing the whistle on an assistant coach or head coach at an institution puts the student in a tricky situation. The laws, as written, remove some of the repercussions, but they miss the more subtle things. They don’t protect you from everyone at work hating you, or you becoming the least popular guy on campus. There are reasons some people fear the repercussions of reporting. Another thing that would halt their reporting is if they don’t suspect enough. They may say to themselves, “I’m suspicious of abuse happening, but not suspicious enough.” The threshold for what is fair to report is very low. But as an individual, people want to be certain. No one wants to get anyone in trouble if they’re not sure. People try to become investigators, and that’s not what the law tells them to do. The law just says report. The laws are different in different states, but when you think about the bigger issues such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, and neglect, the laws are pretty clear. It becomes trickier when it comes to suspected emotional abuse.

Contact information for members of the media:

Seth Kalichman, Ph.D.

Professor, Department of Psychology, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

Center for Health, Intervention & Prevention

University of Connecticut

Phone: 860-486-4042 or 860-208-3706

Website: http://denyingaids.blogspot.com

Email: seth.k@uconn.edu