The first doctor we get to know, the doctor who treats the whole family, and the one we want to be like is our PCP (primary care provider). The current generation of residents can relate to the family doctor who always answered our phone calls day or night, patiently addressed our concerns, greeted us warmly during our clinic visits, and attended our major family events.

That’s why a good percentage of medical students and residents aspire to becoming primary care providers in the beginning of their training. But by the end of their education, many decide instead to specialize. Why do so many aspiring family doctors change their mind? Especially now, when so many PCPs are retiring and health care reform has prompted an even greater need for PCPs?

The answer lies in addressing the core issues of the problem. Even the recent proposals about salary hikes for PCPs have not yet provided enough incentive for young medical trainees to change their career path. Interestingly, many specialties are under-paid or paid at par with primary care. Why do we still lack the flow of qualified personnel in that direction? This is mostly because, at the bottom of our hearts, we all want to practice medicine – real medicine. Once medical residents start training, we realize that being a PCP is spending around 10 percent of our time with patients and 90 percent with papers and electronics.

Every clinic day, a pile of forms that we fill and refill, send and resend, will be waiting on our desk, even before the first patient arrives. After the initial battle of sorting them out, we are called in for some real action – providing care to our patients. After about 10 minutes with each patient, it’s paper time again. It is all about documentation. The golden rule is that “if something was not written down, it was never done.” Toward the end of the clinic, the residents and supervisors are buried in piles of paper – editing notes, filling out disability forms and a multitude of other documents.

The case is the same for hospitalists. No matter how glorified hospital medicine is, there is still a lot of paper work to be done. The focus is mostly on filling out the right forms, following the proper protocols and writing detailed notes to describe to case managers and insurance providers every hospital event related to the care of a particular patient.

This is in stark contrast with what is required of specialists. Whether it is an inpatient or outpatient scenario, almost every paper except those regarding their specific area of expertise, can be sent to the patient’s PCP. That’s why the specialist has more time for patient care and academic activities. Needless to say, the residents and medical students learn more medicine from the specialists and more clerical work from the hospitalists. No wonder they choose to practice real medicine by becoming a specialist and not a clerk by practicing primary care or hospital medicine.

The other reason so many of us are choosing specialties involves playing the game of defensive medicine. Gone are the days when the PCP was our best family friend and nobody would think of questioning his or her decisions. Malpractice cases are highlighted by the media, and attorneys encourage a hostile and defensive barrier between the PCP and patients. Patients are now viewed as potential malpractice cases and physicians are not confident enough to treat a patient without the necessary, and many unnecessary, diagnostic tests and evaluations. Primary care is one of the most sued sections in medicine due to the multitude of medical conditions they have to deal with.

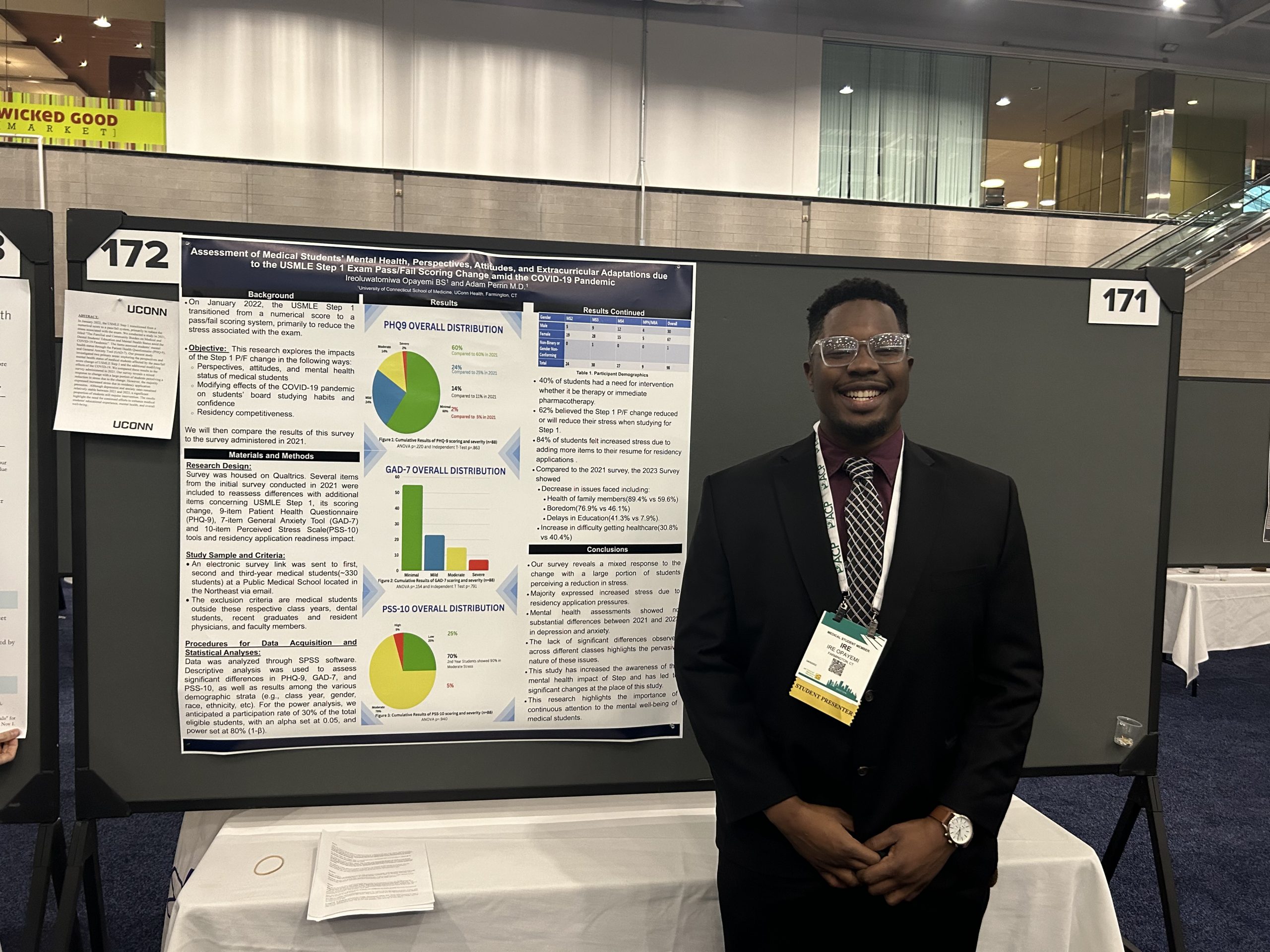

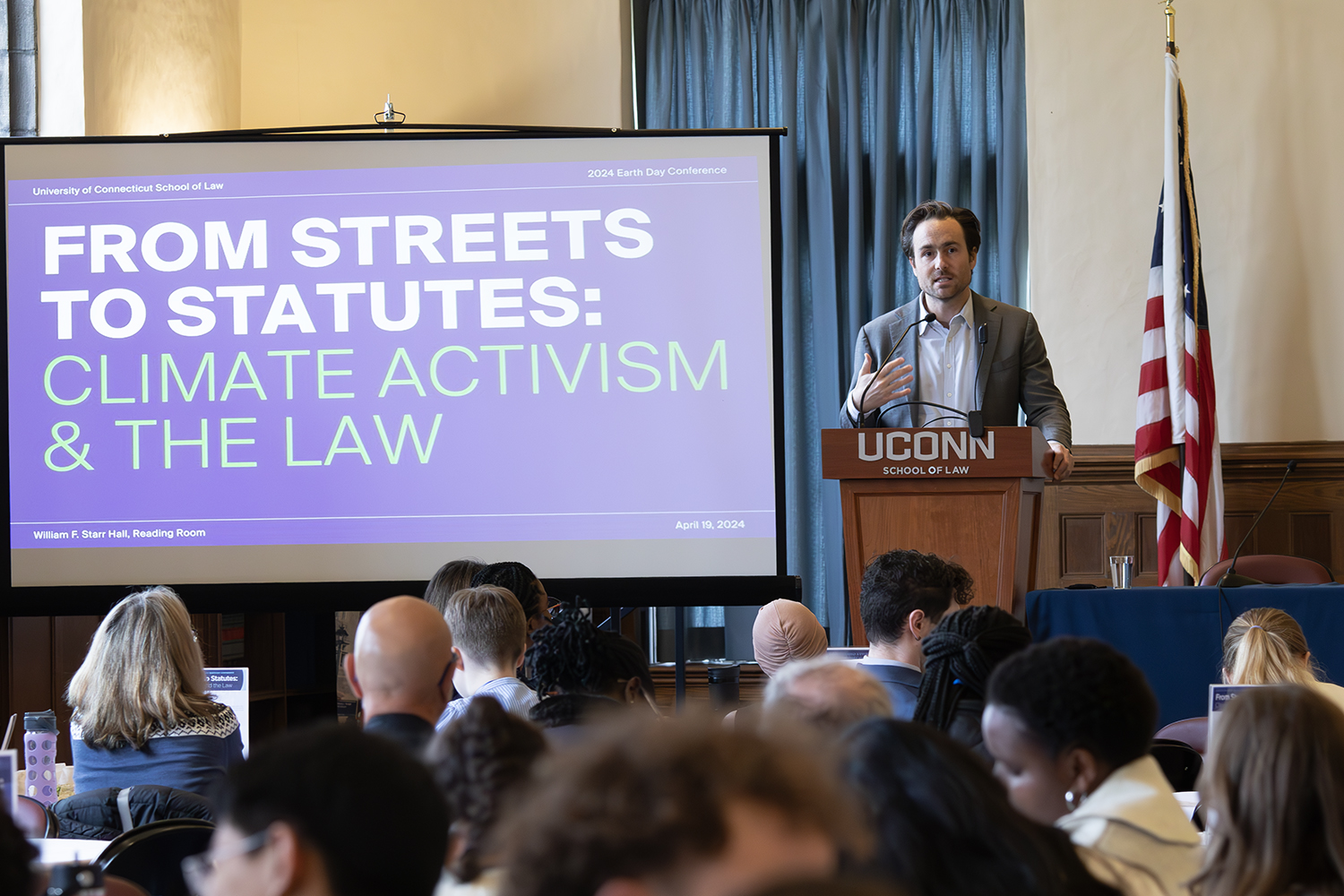

The need of the hour is for the emergence of residency programs emphasizing primary care medicine, like the one at the University of Connecticut. A healthier approach to practicing medicine, in terms of reducing the clerical aspects of the job, is expected to make a major difference. This would provide more quality time for patient care and building a strong physician-patient relationship, which is key to the success of any primary care provider. Above all, we need to approach the issue through the eyes of a young medical trainee aspiring to practice real medicine.

Follow the UConn Health Center on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.