At critical junctures, the personality and vision of a powerful figure may shape the direction of history. One such period was 1945-46, when the onset of the Cold War froze links that had been forged during World War II between the Soviet Union and the West.

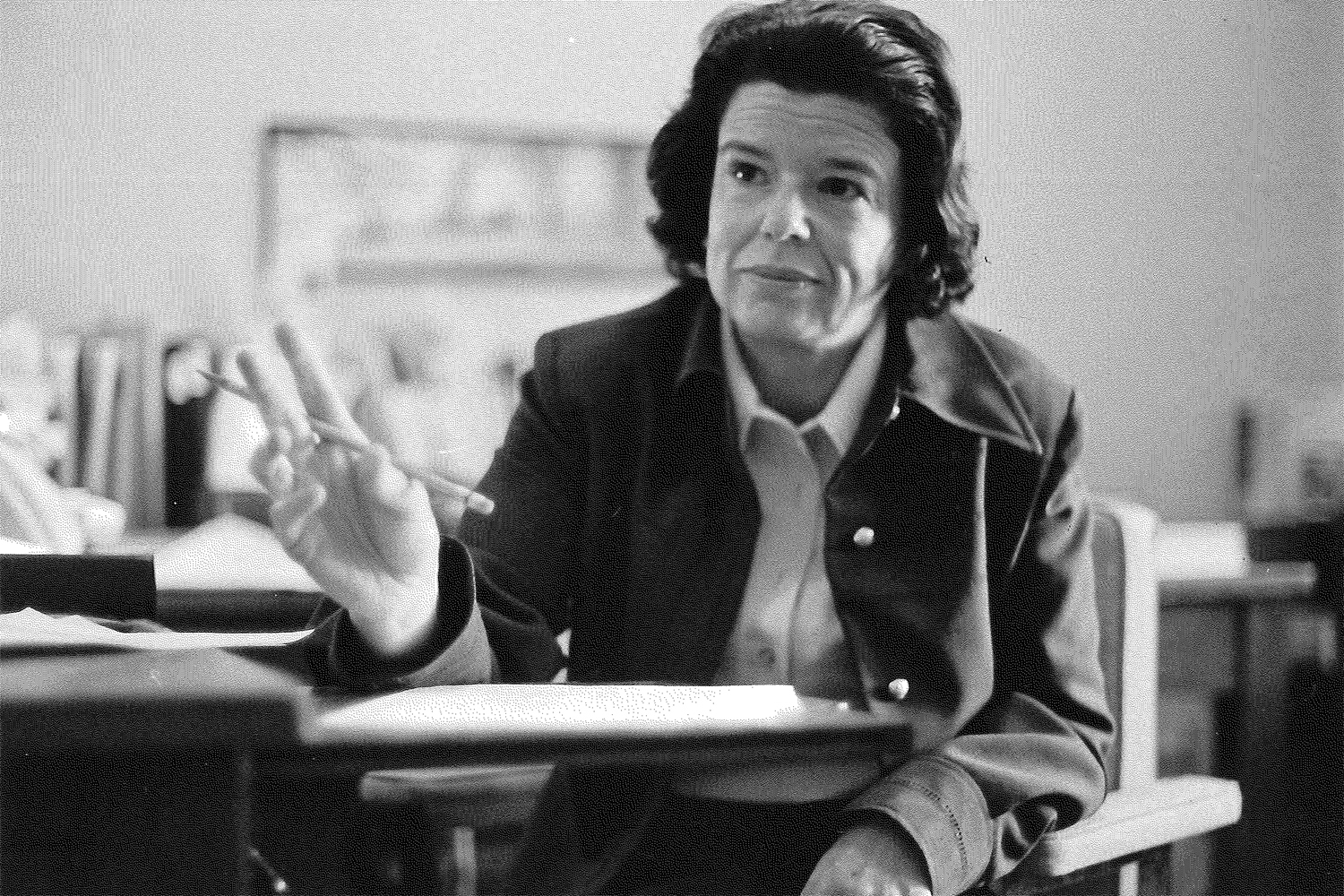

That is the thesis of a new book by history professor Frank Costigliola, Roosevelt’s Lost Alliances: How Personal Politics Helped Start the Cold War (Princeton University Press).

“History is more contingent than we think,” says Costigliola. We tend to underestimate how events are shaped by the personality, emotions, and cultural assumptions of key figures. Things are more malleable at certain turning points.”

Far from being inevitable, he contends, the Cold War settled in after the sudden death of a key player – Franklin Roosevelt, whose personal relationship with Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill had strengthened the Big Three alliance against the Axis powers in World War II and whose political skills might well have kept the alliance going after the war.

During the war, Roosevelt overcame the prevailing cultural prejudices of Americans, who saw Russia as a primitive, backward country, and of Russians, who felt insecure and that other powers were condescending toward them. He gained significant support from Stalin by showing him respect, says Costigliola.

As the war wound down, Stalin, concerned about Japan and Germany quickly regaining power and seeking revenge, wanted to keep the Big Three alliance going. Churchill, worried about his own reelection, played a double game, telling Stalin that his public anti-Soviet stance was merely an election strategy but also using it to bolster the U.S.-British alliance. Roosevelt had to contend with growing anti-Soviet factions in his own State Department and in the political arena.

Roosevelt was laying the groundwork to continue the Big Three alliance after the war, but his death in April 1945 from a brain aneurysm changed things in a day, Costigliola says. Harry Truman, who had been vice president for only three months and had been kept in the dark about Roosevelt’s plans, soon took a hard line against the Soviet Union.

Churchill lost when the Labour Party won parliamentary elections in Great Britain in July 1945. Labour leaders had little sophistication in foreign affairs, and Truman (“the buck stops here”) also liked simplicity and unambiguous solutions, Costigliola says. That year saw dramatic changes – Roosevelt died, the war ended, Churchill was defeated, the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Japan, and Japan surrendered.

In a time of drastic, turbulent change, says Costigliola, “you saw people in both Russia and the West grasping at ideology as a means toward certainty.”

Anti-Communism took hold in the West. By March 1946, Churchill, now out of power, regained the headlines by warning of a new conflict, which he later named “the Cold War.”

“I don’t mean to whitewash Stalin,” Costigliola says. “He was a cruel and murderous dictator. But Cold War was not what he preferred.”

While Roosevelt had planned to aid Russia after the war, and polls showed that stance was supported by 80 per cent of Americans, Truman took the State Department’s advice and decided to rebuild Germany instead. Stalin turned to the Eastern European countries that Russia controlled, dismantling their factories and using the equipment to rebuild a shattered Russia, Costigliola says.

While Roosevelt had planned to tell Russia that the U.S. had made an atomic bomb, and top American generals even favored having Russian observers at the Los Alamos bomb test, Truman determined to hold onto the “secret.” The Russians already knew much of the physics involved, and their spies were stealing many of the engineering secrets. Truman, however, clung to his belief in American exceptionalism – that only “Yankee ingenuity” could produce a bomb, Costigliola says.

He was wrong. The Cold War and the atomic arms race soon eliminated any chance that history might have gone in a different direction.

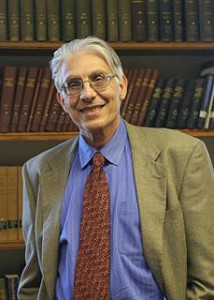

Costigliola is now on sabbatical leave at Princeton, where he is editing the diaries of George F. Kennan, one of the State Department experts whose anti-Communist views persuaded Truman. Costigliola has taught at UConn since 1998 and has held fellowships from the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Guggenheim Foundation. In 2009, he was president of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations.

Read Costigliola’s recent New York Review of Books article about John Lewis Gaddis’s new biography of Kennan.