UConn researchers, backed by a $3 million federal grant, are beginning an ambitious project aimed at understanding why some urban schools are excelling in science education, research that could ultimately change the way the subject is taught around the country.

The five-year School Organization and Science Achievement Project, funded by the National Science Foundation, will examine science education not only in the classroom, but in terms of the entire educational environment.

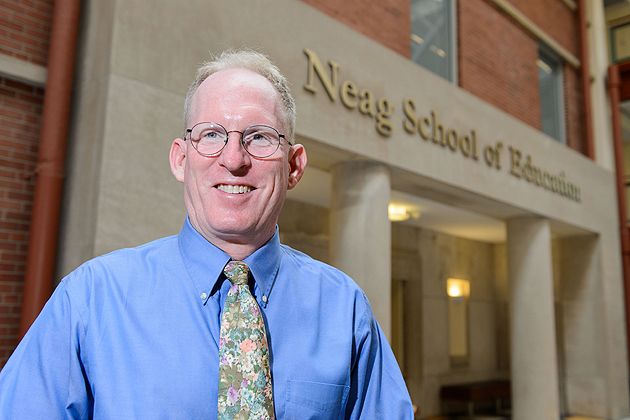

John Settlage, an associate professor of curriculum and instruction at the Neag School of Education and the principal investigator, says the idea for the project came from studying elementary science test scores. What was surprising was that certain urban schools in Connecticut were outperforming not only their city peers, but also many suburban schools.

That prompted researchers to look beyond what happens in classrooms to learn how successful science performance arises from systems of relationships. This includes examining all stakeholders, from the school principal to the lead science teacher, and even parents and volunteers who partner with the school.

“We’re taking an ecological view of science education,” Settlage says. “How we teach science is obviously important, but we should not ignore the bigger picture. The interactions among people throughout the school, including with the surrounding community, all contribute to children’s science learning.”

You can be the best science teacher in the world, but if you’re not in the right environment and there is not solid leadership, then those problems will show on the science test.

Settlage and his fellow researchers know many outstanding teachers and administrators. But they say that beyond personal traits, institutional factors are also influential in shaping a school’s science program. Once those factors for success can be identified, the information can benefit other schools seeking to improve.

“This is a solvable problem,” he says. “The superhero teachers and administrators don’t come from other planets. They came up through the system.”

Science has moved to the forefront of the public conversation on education. President Barack Obama, in his State of the Union address, emphasized the need to hire thousands more science teachers over the coming decade. At the state level, the economic vitality of Connecticut requires developing scientific literacy beyond just future engineers and scientists. Otherwise, if uneven success in schools continues, it will translate into unequal access to college and career options for some students. Settlage’s study promises to shed light on improving the quality of all children’s science experiences.

A multidisciplinary project, UConn researchers joining Settlage are educational statistics specialist Betsy McCoach; educational leadership experts Morgaen Donaldson and Anysia Mayer; and post-doctoral fellow Regina Suriel. The researchers are currently working to firm up arrangements with school districts, including Hartford, New Haven, and Bridgeport. In total, the School Organization and Science Achievement Project will involve 150 schools in Connecticut and Florida, where researchers at the University of Central Florida are collaborating with the UConn team.

Ultimately, the goal is to craft a set of recommendations about school leadership and organization practices that can be used by educators around the country, to help provide the kinds of school environment where science teachers and science students can thrive. These efforts will also inform UConn’s science teacher and school administrator preparation programs.

“You can be the best science teacher in the world,” Settlage says, “but if you’re not in the right environment and there is not solid leadership, then those problems will show on the science test.”