If you know one thing about Irish-English relations, it’s that their story is rife with conflict.

The turn of the 17th century saw the complete conquest of Ireland by Britain, resulting in a mainland-colonial government, dispossession and oppression of the Irish people, and the ever-growing struggle between Catholics and Protestants. You might say the two nations have been at it ever since.

But perhaps there’s more to these early modern Irish-English relations than we think.

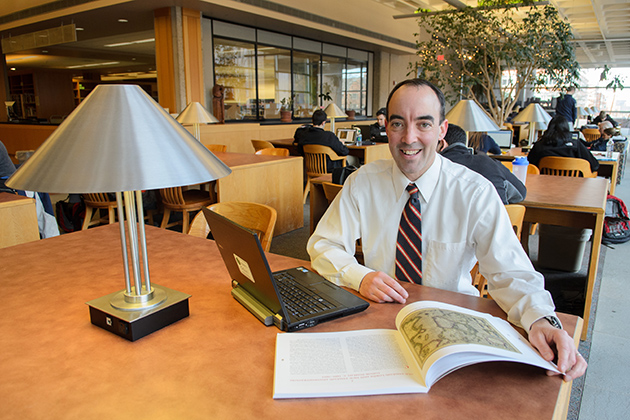

Irish-American Brendan Kane, associate professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, affirms that the history of these nations has been bloody.

“But, it’s not ‘Ne’er the twain shall meet!’ and ‘A pox on all their houses!’ as many think,” Kane says. “I want to remind people that there’s a whole other realm here.”

Evidence that some Irish and English actually liked and cooperated with – as well as fought – each other has inspired a new exhibit that Kane, with colleague Thomas Herron of East Carolina University, has curated at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

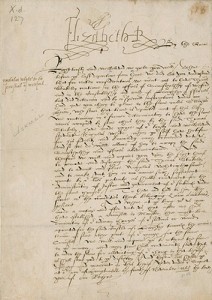

The exhibit, whose opening reception on Feb. 4 was sponsored by the Irish Embassy, uses paintings, maps, correspondences, books, photographs, and spoken word recordings to show the cultural influences between Ireland and England during the reigns of monarchs like Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

The exhibit’s title, “Nobility and Newcomers in Renaissance Ireland,” points to the fact that there were Irish and Norman-descended nobility established in Ireland before the island was made a kingdom under the English crown in 1541. The English, under the reign of the Tudors, then came to the island to govern it.

“The exhibit focuses on the nobility, as those are the people that have left the best records,” says Kane. “Their lives demonstrate the interaction, as well as the conflict, between these realms.”

In those days, noble families created pedigrees, so their family history was easy to trace. And often the family crests evolved along with them. The exhibition shows several examples of Irish-English families whose coats of arms meshed with one another over time.

The exhibit also explores the Irish, or Gaelic, language. On display is an Irish language primer given to Elizabeth I during her reign by a nobleman of the Nugent family. The exhibit has a mobile device app that lets visitors to the exhibit and its website listen to bits of the spoken Irish and English translations.

Having lived in rural Galway for two years, Kane is fluent in Irish and especially excited to illustrate the language .

“Lots of people don’t think Irish is a real language – they just think it’s an accent,” Kane says.

Early in his life, Kane thought he wanted to be an astrophysicist. He studied the subject at the University of Rochester, but in the end, his heart wasn’t in it and he found his real passion in history.

Kane grew up in an Irish-American family, so bits of the Irish culture had worked their way into his childhood. When he moved to Philadelphia, he discovered a Penn night class in Irish, and decided to “give it a go.”

Eventually he moved to Galway, where he attended the National University of Ireland and worked in a bar. The latter, he says, is where he really got his education.

“Sometimes new people would talk about me in Irish, not realizing I could speak it,” he says wryly.

Now the associate director of UConn’s Humanities Institute, he’s not sorry about his circuitous route to what really enthuses him: the history of his own heritage.

“I didn’t take a straight line to where I am now,” he says. “But doing this is not just for historical purposes: it helps me and hopefully the people who see the exhibit think differently about contemporary Ireland.”

Take an online tour of the exhibition, complete with audio, at the exhibit’s web site.