For the 2015-2016 academic year, the UConn Reads Steering Committee has selected the theme “Race in America.” The theme is both provocative and poignant, especially in juxtaposition to various current events (such as Ferguson, Baltimore, and #blacklivesmatter) and several significant anniversaries, including the 50th anniversaries of the March on Selma and the subsequent passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The year 2015 is also the 50th anniversary of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which removed – for the first time in U.S. history – race-based, nation-based quotas from immigration law.

The committee welcomes your nominations for the 2015-16 UConn Reads selection, which can be submitted online. The deadline for nominations is Aug. 1.

The weary expressions of the young, armed soldiers that boarded my bus in Chiapas, Mexico betrayed a fear of discovering the target of their search. It was early January 1994 and only a week earlier, at the turn of the New Year, two simultaneous events had changed the course of the country’s history and also my own relationship with Mexico. The military conscripts were searching for clandestine members of the newly formed Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), a group of indigenous campesinos (farm laborers) who had rallied under the banner of Emiliano Zapata, Mexico’s historical and mythologized agrarian revolutionary, to resist the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

That moment of potential violence was embedded in a long history of domestic state repression and foreign economic imperialism. Spanish colonial officials and then Mexican politicians had long since subordinated the country’s indigenous populations, while forging trade relations with foreign governments. The newly formed Zapatistas knew this history well, and understood that another “free” trade arrangement would create further disruption and dislocation in their communities, in some cases forcing the option of emigration to the United States. They also knew that leaving their homes behind for el Norte meant facing a new racial regime as immigrant outsiders.

NAFTA’s central focus on the unrestricted flow of goods through Canada, the United States, and Mexico ignored the protection of land and labor. As the government continued to erode the foundations of Mexico’s 1917 progressive constitution, communities like those in Chiapas lost their ability to compete with highly subsidized multinational corporations. Thousands lost their land and, once displaced, headed north to the border where they faced the treacherous choice of migration.

This was only the latest chapter of Mexican migration, a story advanced for decades by these kinds of (neo)liberal economic interventions. Mexican migration to the United States has comprised the world’s largest sustained movement of migratory workers in the 20th and 21st centuries. As part of the massive post-World War Two wave of migrants from across Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, in recent decades Mexicans have comprised by far the largest migrant group in the United States. Although frequently cast as peripheral to projects of nation-state formation and consolidation, over the past 160 years Mexican migrants and migration have played central roles in the economic and political development of both countries.

Throughout the 20th century, following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, and to the present day, U.S. immigrant legislation has consistently and strategically constructed the Mexican migrant first as a temporary and then as an illegal, unassimilable racialized other, a permanent outsider used to fill the critical labor demands of an expanding industrialized economy.

For its part, Mexico, always in an asymmetrical political and economic position vis-à-vis the United States, initially used a series of uncoordinated emigration policies to attempt to prevent the flight of its working citizens, and then during and following World War II changed its broad legislative priorities to facilitate an out-migration that yielded economic gains through remittances and relief from unemployment and rapid population growth.

Recently graduated from college, in 1994 I had crossed the border back to Mexico on a kind of historical pilgrimage to reconnect with my extended family there. Like thousands of other Mexicans, my mother and her family emigrated to the United States during the post-World War II period, a time when the two countries legislated a temporary worker or “bracero” program. They arrived in Chicago, where her father, my abuelito, labored as a janitor and night watchman in Wiebolt’s department store, her older brothers left to serve in the military and fight in the Korean War, and mi mamá learned English and three years later graduated from high school.

Years later she would meet my father, a Methodist minister from Ohio, at the Church Federation of Greater Chicago. There they worked with the city’s homeless, new immigrant and refugee communities, alongside Edgar Chandler, a champion of civil rights and close friend of Dr. Martin Luther King. Together, my parents crossed a different kind of border in 1965, when it was still illegal in some states to have a mixed-race marriage.

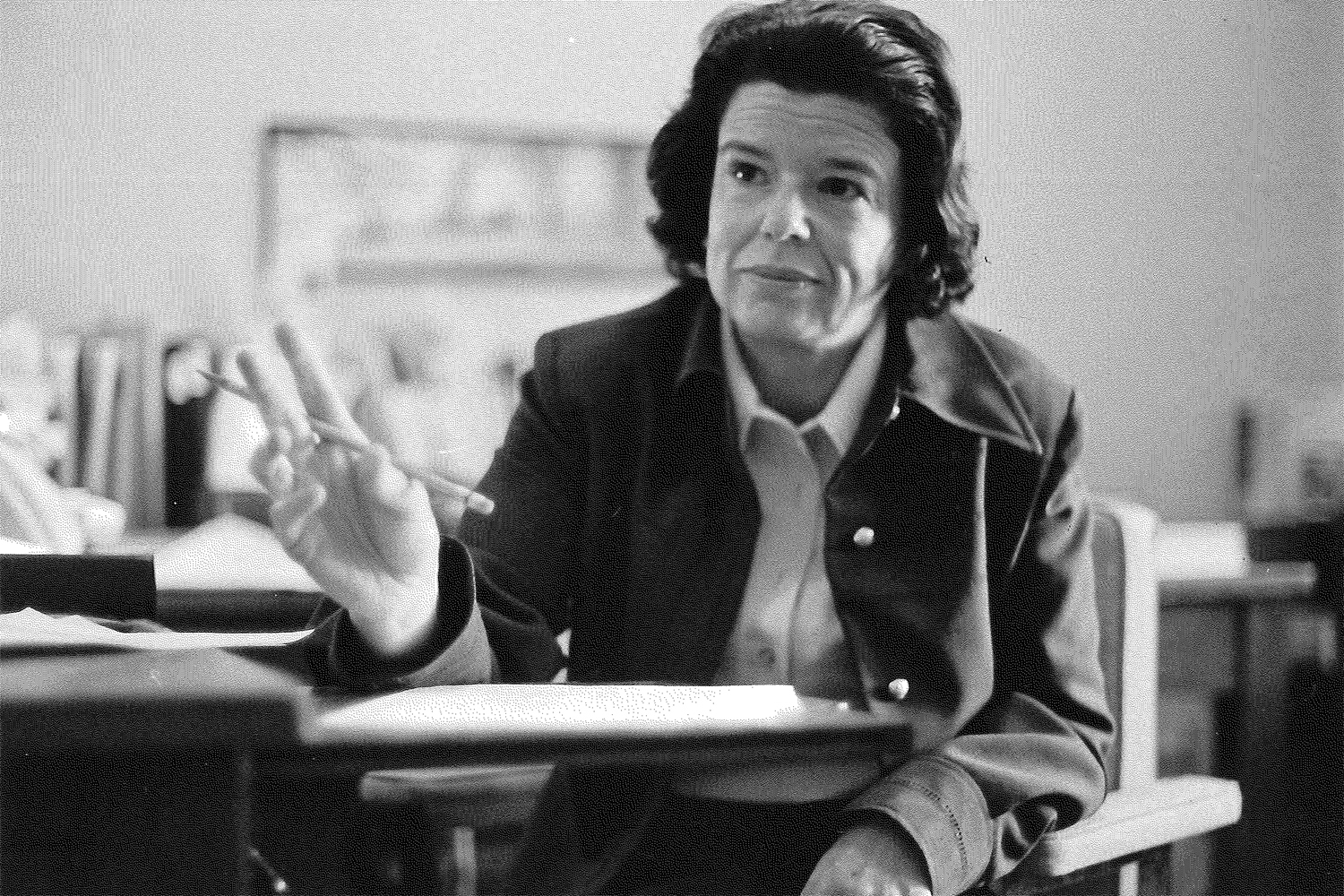

Guided by my parents’ personal experiences and struggles for racial justice in the U.S., my EZLN/NAFTA encounter in Mexico challenged me to question the relationship between these two countries and their relationship to my family’s history. Back in the U.S., while searching for some answers to these questions in graduate school and then as a history professor, I have always tried to integrate my research and teaching with solidarity work with migrants in both countries. My publications, teaching, and political activism were profoundly shaped by that moment on the bus in 1994.

I’ve turned to a wide range of books and other materials to better understand the broader contexts and contingencies of my Mexican family’s migration to the United States and, along the way, my own history of Race in America. My “reading” of migration is eclectic and includes written, aural, and visual materials. Here’s a sampling of “reads” roughly organized by discipline or genre. Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (Chicana/Queer Theory) and Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s The New World Border (Performance Art) have provided me powerful ways of theorizing and thinking about migration, race, and the nation-state.

Carlos Fuentes’ La frontera de cristal (The Crystal Frontier, Novel); Juan Felipe Herrera’s (2015 U.S. Poet Laureate) 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments 1971-2007; Lila Down’s Border/La linea (music); Lalo Alcaraz’s Migra Mouse: Political Cartoons on Immigration (Comics); and Ernesto Galarza’s Barrio Boy (Autobiography) all offered me insights from the perspective of the migrant him- or herself, giving details on the departure, crossing, arrival, and (often) return.

Pierrette Hondagneau-Sotelo’s Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning & Caring in the Shadows of Influence (Sociology); Seth Holmes’ Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States (Anthropology); and Aviva Chomsky’s‘They Take our Jobs!’ and 20 Other Myths about Immigration (History) helped me to situate the experience of Mexican migration in its complex historical and sociological contexts.

The UConn Reads program was created to bring together the University community – from students, faculty, and staff to alumni and friends of UConn, as well as citizens of Connecticut – for a far-reaching and engaging dialogue centered on a book suggested by the community.