The stress of prolonged exposure to painful medical procedures can have lasting negative impacts on the brains of a hospital’s tiniest patients – infants born prematurely.

A team of UConn researchers is now working to find ways to minimize or prevent this stress and improve the overall outcome for Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) patients by analyzing one of the most extensive sources of information those patients provide: poop.

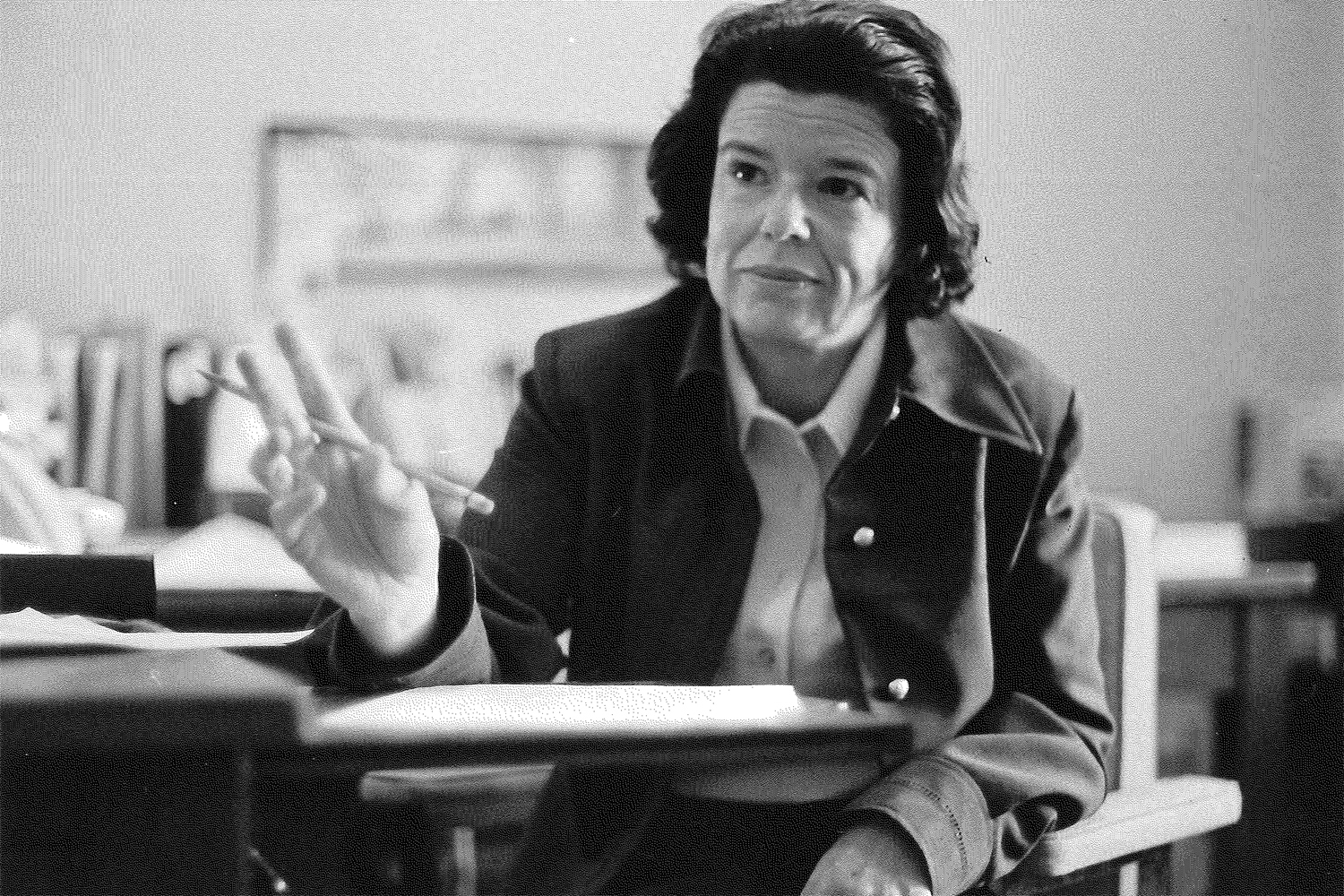

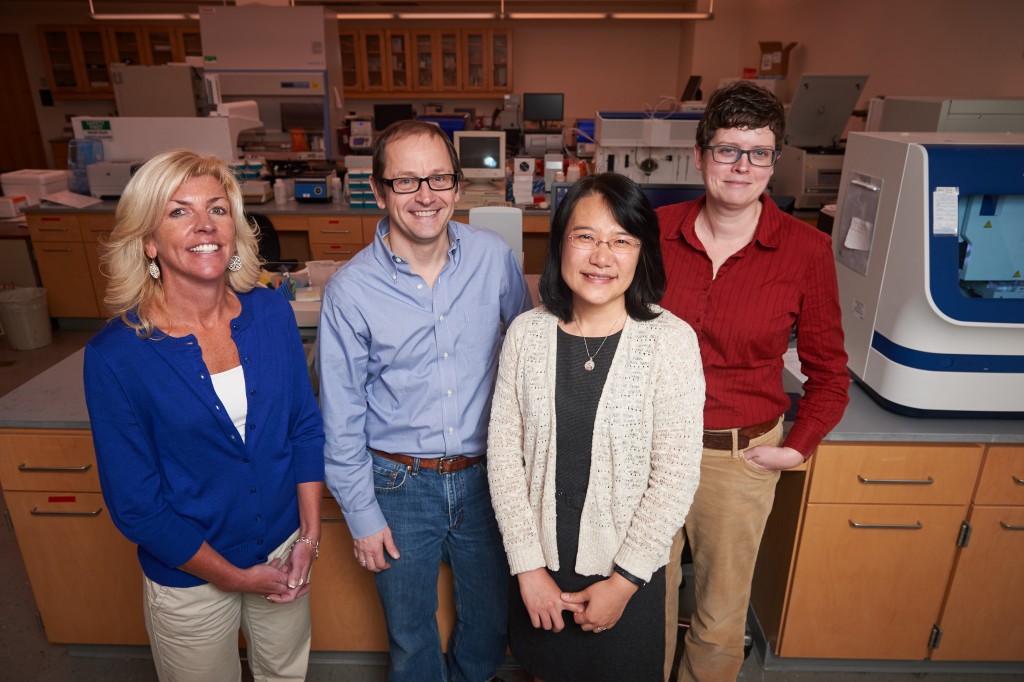

In the new study by Xiaomei Cong, associate professor or nursing, and Joerg Graf, professor of molecular and cell biology, fecal samples are collected to study the patient’s microbiome, which may help communicate details that the babies are unable to.

“Babies can’t use the 0-10 pain scale like adults can. We can only tell their pain by looking at vitals or expression, perhaps by measuring cortisol and other stress responses,” says Cong. “We hope to look at gut microbiome patterns and the bi-directional communication between the gut and the brain.”

This constant communication, which scientists are only just beginning to understand, may help improve the care of these tiny patients, which affects a surprising number of families.

Fully one in nine babies born today arrive prematurely, and the measures necessary to keep them alive are numerous, often painful, and may have long-term effects. The stress can affect neurological development, resulting in lower IQs and neurodevelopmental challenges.

“The overall goal of this work is to see if we can pick up microbial signals that will allow us to make predictions about neurobehavioral development,” says Graf.

Cong’s tone is empathetic as she describes the difficulties NICU babies endure each day: “Cumulatively they may encounter over 100 painful procedures in their stay,” she says. “These include heel sticks and other blood draws, IV line placements, and central line placements, all of which are very painful.”

Searching for clues in the gut microbiome

Our microbiome is essentially everything that resides within us that is not “us,” including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Members of our microbiome are so numerous they outnumber our own cells 10 to 1 and are proving to have huge impacts on our health and physiology.

The organisms composing our microbiome are not freeloaders – they are quite the opposite. A healthy microbiome’s important roles include helping to prevent serious infections, keeping our organs functioning normally, processing vitamins, and helping regulate stress and neurological function.

The study involves collaborating with the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center NICU to recruit babies. Researchers carefully track their daily treatments, charting procedures, medications, feeding type and parental contact over a three-week period. Procedures are ranked based on their pain level in order to track the babies’ accumulated stress. Over these three weeks, fecal samples are collected, frozen, and sent to the UConn Microbial Analysis, Resources, and Services or MARS facility.

“That is why we sometimes call this ‘the baby poop-sicle project’,” jokes Cong, whose work in this area earned her the young investigator poster award from the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Researcher Susan Janton extracts the microbial DNA from the samples, and the DNA is analyzed and compared to the babies’ daily routine and neurodevelopment to see if there is any correlation between changes in the microbiome and procedures the babies have undergone.

Colorful, dazzlingly complex charts are the result of compiling the data, giving insights into the delicate interplay of microbiome population dynamics and the stresses of patient care.

“There are so many variables to consider,” notes Graf.

Teasing out the trends is key for determining whether the microbiome can predict neurodevelopmental outcome for NICU patients. Clues about how to promote a normal healthy microbiome may also improve the patients’ outcomes.

A pilot analysis has yielded promising results, says Cong. “In the NICU, we can supplement with mother’s own milk. This has already shown to promote more diversity and evenness of the microbiome. Those who are formula fed or have been fed pasteurized donor milk have uneven microbiomes, often with an imbalance resulting in more pathogenic bacteria.”

Considering the importance of a balanced microbiome, Graf adds, “there is a healthy microbial community that an individual can have. There is such great variability between individuals even. These kids have really underdeveloped intestines, which makes them more susceptible to infections.”

This research, funded by an Affinity Research Collaborative award through UConn’s Institute for Systems Genomics, has potential to be translational to NICU care. Other interventions shown to decrease stress and improve neurodevelopmental outcome include increasing parental contact, changing the care routine, and delaying painful procedures for as long as possible.

“When babies are exposed to fewer painful procedures during the first three weeks, they have better neurodevelopment,” says Cong. “We have to try to really limit the procedures, maybe change policies, and educate healthcare providers.”

Although these are early days and the results are preliminary, it is important to communicate the data to other researchers and clinicians, says Cong, “and try to say something on behalf of our smallest patients.”