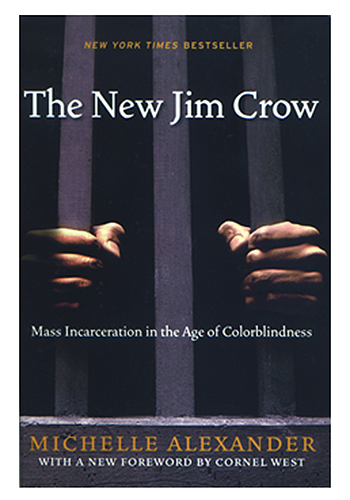

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010) does what all great works of non-fiction should do: it forces us to think about old problems and recurring issues in new and interesting ways.

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010) does what all great works of non-fiction should do: it forces us to think about old problems and recurring issues in new and interesting ways.

When I think about the relationship between legal structures and race relations in this country, my gut reaction is to fall back on a simple and easy-to-understand narrative: that every systemic problem lends itself to a grand legal solution, so long as the motives of those in power are in the right place. By falling back on that assumption, I effectively sidestep many hard truths about how race discrimination and the law actually interact in 21st-century America.

As a child growing up in New York City during the mid-to-late 1970s, I knew that all was not right in American race relations. Nightly newscasts featured troubling reports of protests against controversial busing decrees in northern cities, as well as coverage of urban race riots. Yet I believed (perhaps hoped) that these events would have little or no impact on me personally.

One hundred and twenty years after the Supreme Court upheld the doctrine of ‘separate but equal,’ the final nail for the coffin of Jim Crow has not yet been found.

Though I was one of only two Caucasians in my first and second grade classes at the local elementary school, it never occurred to me that there was something unfortunate about an arrangement that based individual schools’ enrollments on residential housing patterns that were themselves steeped in a legacy of overt racism.

In the early 1980s, I attended a magnet high school in the Bronx that was extremely diverse – perhaps the most diverse high school in the entire city. If the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) had failed to achieve the ideal of fully integrated schools, the troublesome legacy of that landmark opinion failed to make a mark on my own personal experience in the New York City public schools.

When I first embarked on the law as my chosen profession, I believed that if legal advocates and the courts could just get the law right, the rest would take care of itself. The first book that inspired me along these lines was Richard Kluger’s Simple Justice (1975), which offered a painstaking description of the epic struggle for racial equality in America, as conducted by the NAACP in its legal assault on segregation.

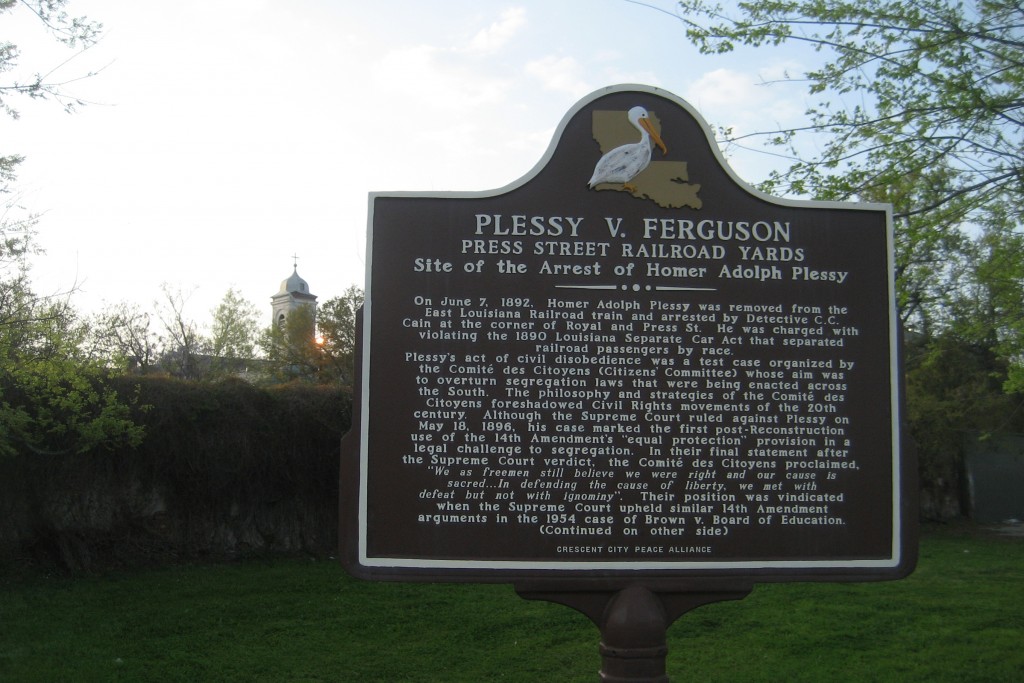

Slowly but surely, Thurgood Marshall, Walter White, and the NAACP’s legal advocates moved the high court from its acceptance of “separate but equal” schools and public accommodations in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) to a full-scale rejection of state-sponsored segregation in Brown. That Marshall was eventually rewarded for his efforts with a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court as the first African-American Justice only confirmed for me that these legal struggles had culminated in the happy ending so many longed for. Ruth Bader Ginsberg was the ACLU attorney who led a similar struggle against legally imposed gender discrimination, and she too was awarded with Supreme Court victories and her own seat on the Supreme Court.

Unfortunately, the nation’s struggle with race relations was too deep and entrenched to give way. As Professor Alexander so eloquently argues, a racial caste system remains in the United States today; it exists in the form of a criminal justice system that targets black men while hiding behind legal formalities that celebrate “colorblindness” and “due process of law.”

No matter how many times we elect an African-American president or eliminate the remaining laws and statutes that explicitly subordinate African Americans, it simply won’t make any difference. One hundred and twenty years after the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, upholding the doctrine of “separate but equal,” the final nail for the coffin of Jim Crow has not yet been found.

Professor Alexander wrote this book for those who “do not yet appreciate the magnitude of the crisis faced by communities of color.” I suspect that makes the audience for her book as wide as the eye can see.

Building on the success of this year’s “Race in America” focus, the UConn Reads Steering Committee has selected next year’s theme: “Religion in America.”

Founded as a haven from religious persecution and envisioned as an asylum of spiritual tolerance, the United States is not surprisingly home to a number of different faiths and diverse denominations; nevertheless, as the increase in anti-Semitic and Islamophobic crimes makes clear, religion remains a contested and central issue in contemporary American life.

The UConn Reads Selection Committee seeks nominations that reflect this upcoming year’s focus; while remaining open to multiple types of nominations, the Committee will not consider specific religious texts (e.g., the Bible or the Quran). Instead, the Committee will consider novels, non-fiction, poetry, and graphic novels. Please watch the Daily Digest for more information about the nomination process.