To break the ice in his Journalism Ethics class, Marcel Dufresne presents students with a list of buzzwords to consider and discuss. So many new ones have emerged in the months before and since the 2016 election that Dufresne recently updated his syllabus to include the terms “Post-truth,” “Alt-Right Media,” and “Fake News” among others.

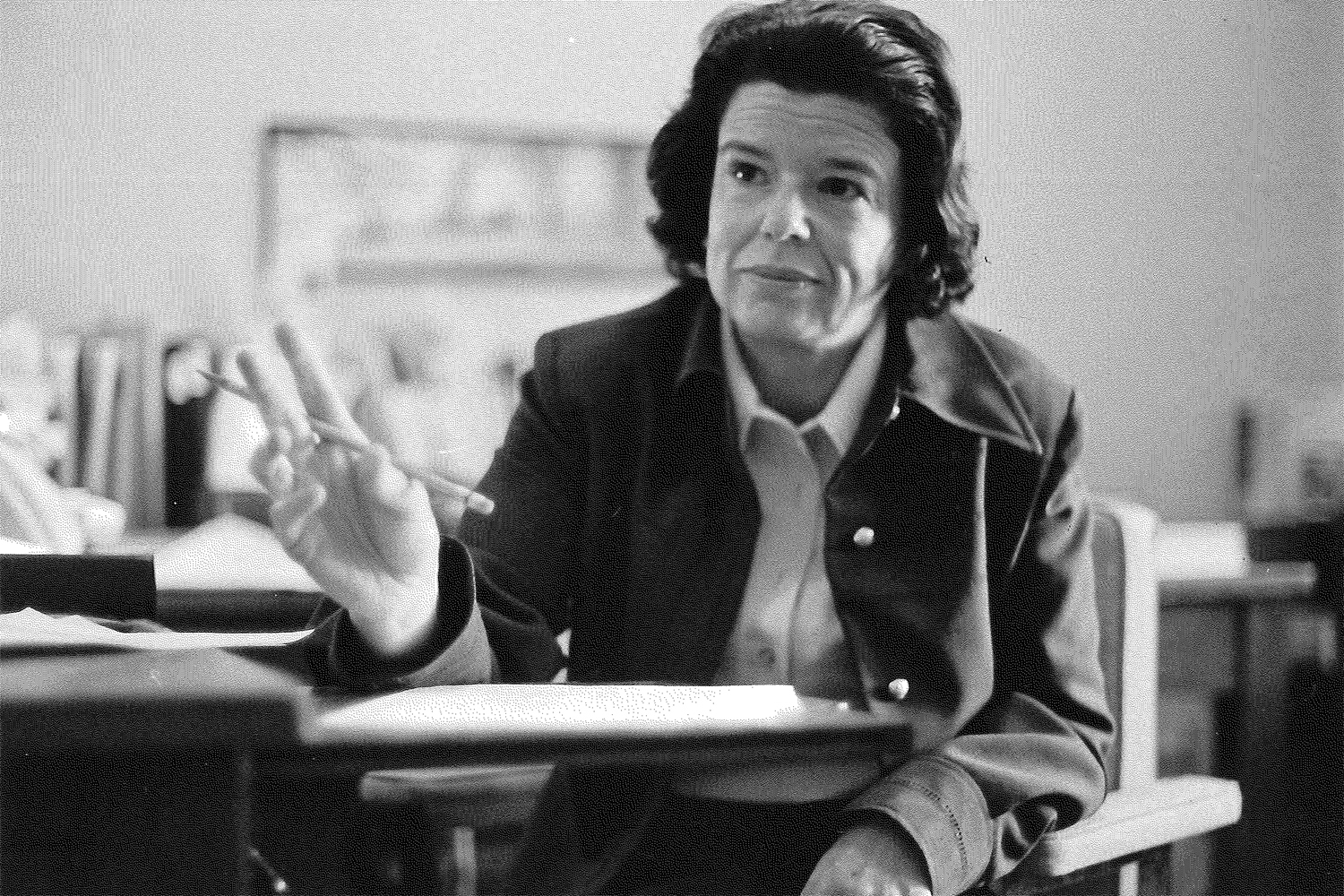

“I say [to my students], ‘OK, these are the buzzwords from our time and we have to grapple with these as we look at traditional ethics,’” says Dufresne, an associate professor who also teaches investigative journalism. “’How relevant are they in relation to what’s going on?’”

I think [students now are] engaged in ways that we haven’t seen in quite some time. — Marcel Dufresne

The question is a rhetorical one, because Dufresne knows that students can hardly see the news or be on Twitter without encountering at least one of those terms daily. The real question for him and other journalism faculty is how to prepare students for the realities of covering news at a time when hostility toward the press is so high and public trust in the media so low?

For Dufresne and his colleagues, it’s an exciting prospect.

The polarized political climate and intrigue swirling around the Trump Administration over questions about Russian involvement in the election, conflicts of interest, and more, has produced a buzz about journalism and a flood of investigative stories not seen since the Watergate era – stories that Mike Stanton, who teaches news writing and a journalism history course, is now weaving into his lessons.

“Today I’m going to talk about libel and the New York Times story about [the harassment suits against Fox News commentator] Bill O’Reilly,” Stanton says. “I ask [my students], ‘How do you handle a story like that and what can you say? How do you deal with that and get it in the paper, and not get sued?’”

Marie Shanahan, an assistant professor of online journalism, has been focusing on the issue of lack of trust in the media and what individual reporters can do to turn that around. One way she does that is to teach students the importance of online reputation and the impact that using social media as a playground can have on their credibility.

“I think that is even more important in this environment,” says Shanahan. “Trust in the media is continuing to erode in general, but also in practitioners and purveyors of the news.”

Shanahan tells her students to Google themselves to find out what kind of personal information about them is already out there – information someone could easily find on them. Since there’s no way they can take back whatever is out there, Shanahan encourages students to publish content they do want to be known for, which will push the other information further down in a search. Her other tips: develop a thick skin when it comes to vitriolic online comments, and spend the $10 or so a year to buy their domain names so others can’t do so to harass them – a retaliatory tactic that the subjects of news stories have been known to employ.

“You are going to be challenged by a segment of the public that doesn’t like what you have to say,” Shanahan tells students. That segment doesn’t want “to believe the facts, including individuals at the highest levels who are calling it fake news. What does that mean?”

Stanton adds that students tend to be respectful of authority, and it may not be in their DNA to challenge or push back.

“I tell them you don’t have to do it rudely, but you have to be firm about it and be firm about your rights,” he says.

Dufresne has been showing the movies All the Presidents Men and Spotlight to get students thinking about how investigative reporters overcome obstacles when gathering information. Earlier this month, Stanton invited Washington Post investigative reporter, Tom Hamburger, to campus to speak to students. Stanton says he is also incorporating the musical “Hamilton” into a unit on the colonial press in his journalism history class, The Press in America.

“When you talk about colonial America – essentially dead white guys – that’s when a lot of eyes start to glaze over,” he says. “But when you can show a clip from the Broadway show ‘Hamilton’ and it’s central to the core debate, or you can talk about how the stuff going on in current politics ties back to those days, it makes students wake up a little bit and get more interested and engaged.”

Dufresne remembers being a college student during the Vietnam era, when the Pentagon Papers came out and enveloped the New York Times in a Supreme Court case that established a new standard in First Amendment law.

“All the stuff we were talking about that was going in the world, it got me interested in politics and current events,” he says. “I honestly see the same thing happening with students now.

“What’s happening in the outside world is immensely relevant to what they are studying in ways that you can’t manufacture. You can’t create that. They are concerned, but they understand what the stakes are, so they are really following the news … I think they’re engaged in ways that we haven’t seen in quite some time.”