“I’m interested in the intersection of the historical and the personal,” says Ellen Litman, a Russian-born novelist, short story writer, and associate professor and associate director of creative writing in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. No wonder she’s interested in that intersection: she’s sitting here in a Starbucks in Storrs instead of heating up a samovar in a Soviet-style flat in Moscow.

And all because of one historical moment that changed her life forever.

It was 1990, and the heady reforms of Perestroika had begun to brew up a backlash. One night, a prominent general went on state television to call for new pogroms against Soviet Jews, darkly insisting that Russia should be for Russians only. “The Chechen war hadn’t started yet,” recalls Litman, who is Jewish. “The Chechens would soon replace Jews as the main enemy. But at the time, Jews were still being watched.”

Her parents decided it was no longer safe to stay, and began the arduous process of applying to emigrate. In 1992, when Litman was 19, her family of four finally arrived in Pittsburgh, where an aunt already had settled. That raw, traumatic, sometimes bleakly funny adjustment period informs Litman’s debut book, The Last Chicken in America: A Novel in Stories (Norton, 2007).

The book’s linked stories thread through one main character, teenage Masha, and those who share her Squirrel Hill neighborhood in Pittsburgh. The New York Times Book Review positively clucked about Chicken: “It’s warm, true and original, and packed with incisive, subtle one-liners.” In 2008, Litman was a finalist for the New York Public Library Young Lions Award, given to promising writers under age 35.

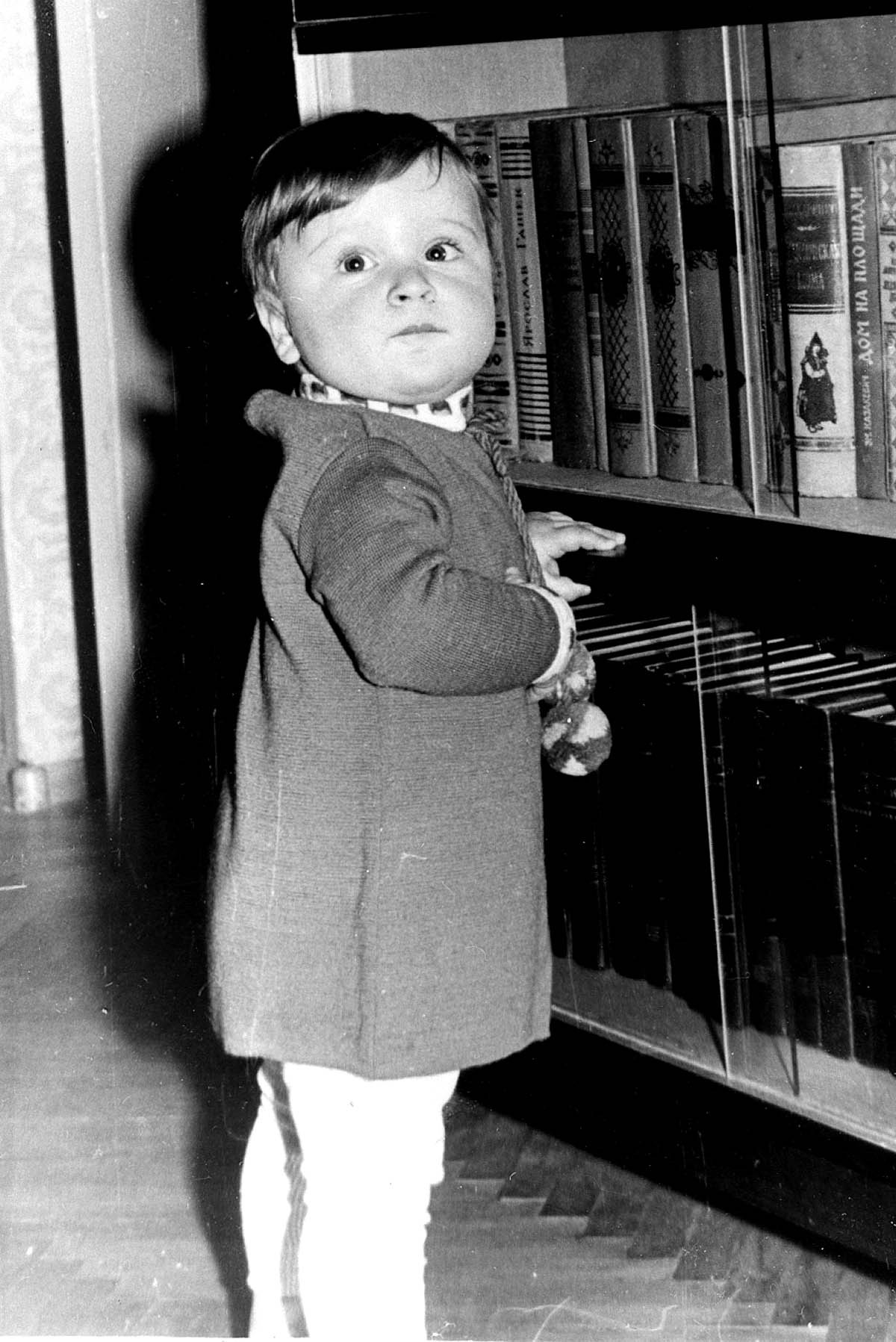

In 2014, her second book came out, also from Norton: Mannequin Girl, a sharp, poignant coming-of-age novel that reads uncannily like a memoir, since it’s about a young Russian Jewish girl who has scoliosis (or curvature of the spine, as Litman has) and must attend a government boarding school for others similarly afflicted (as Litman did).

Several novelists showered praise on it: Margot Livesey called it “entrancing and evocative” and Lara Vanpyar called it “beautiful and tender.” Wally Lamb ’72 (CLAS), ’77 MA called Kat, the protagonist, “the kind of character I love: an endearing, flawed, vulnerable young person who can be cruel one moment, compassionate the next, haughty in her insecurity; hormonal and humane in equal measures.”

Today, Litman lives with her husband and two young daughters in Mansfield. Last semester, she taught two classes in Storrs: Graduate Creative Writing, which studies works that overlap in genre, such as graphic novels or prose laced with poetry, and Honors I: Literary Study Through Reading and Research on immigrant narratives. That second one, of course, hits close to home.

We caught up with Litman one snowy day this past winter at the Starbucks on Storrs Road, chatting against the din of competing student conversations and coffee beans in mid-grind. She wore a quintessentially American fleece jacket but also fur-lined boots right out of “Doctor Zhivago.” The sun streamed over her wheat-colored hair as she sketched out, in a lyrical Russian accent, her personal history.

Q: Let’s start with your neighborhood in Moscow. Was your world “orderly, like a sheet of ruled paper, like hopscotch squares,” as you write in Mannequin Girl?

Litman: All the apartment buildings were identical. Tall cement boxes, light gray, built in the ’60s and ’70s. We lived in the northwest of Moscow in one of the new neighborhoods. Outside every apartment building entrance, a group of grandmothers would sit, socializing. They minded your business and always told you what you were doing wrong!

Q: Your father was a chemical engineer and your mother taught math. Your sister has worked in IT for Amazon and Microsoft. You went to the Moscow Institute of Electronics and Mathematics, got a B.S. in information science from the University of Pittsburgh, and had a career in IT in the U.S., too. Your whole family was good with numbers – but you ended up making a living from words. How did that happen?

Litman: In Russia, you simply couldn’t be a writer if you were Jewish. You couldn’t aspire to certain things. We were taught very early that you have to work twice as hard as others to get things. I kept a journal and wrote poetry, but there was no way to “be a writer.”

You have to understand that Russian Jews were never considered Russians. On my passport under nationality, it said “Jewish,” not “Russian.” Being Jewish affects a lot of things, unofficially and officially. Which college you can attend, which job you can get. Some colleges won’t accept Jews because “they have bad vision.” Others admit under a quota from the local party district.

Q: In Mannequin Girl, you write this of Kat: “She’s scared of changes … they’re almost never good. They start with this thinly veiled secrecy – a dismissal, a smile, a cryptic hint – only to explode in your face, breaking your life into bits, scattering them without a second thought.” Like Kat, you were diagnosed with scoliosis as a little girl, had to wear a brace until you were a teen, and had to go to a special school. How did the diagnosis change your family’s story?

Litman: It transformed our whole life. I was 3, and would start school when I turned 5. We had to move to a new neighborhood closer to the Number 76 School, which treated children with scoliosis. In Russia then, you couldn’t just move and buy or rent another place. You had to go to an exchange bureau and organize a swap, our apartment in our neighborhood for someone else’s apartment in another neighborhood. My mother quit her job in order to work at my school.

In the world we lived in, we did not know about bad illnesses or situations, so we didn’t know what to do when we learned I had scoliosis. A lot of things were kept out of the society. If a child had limitations, that child was hidden from the world, sent to a special school.

When we first immigrated to Pittsburgh, I wondered why there were so many disabled people on the streets, on the bus. Then I realized that it wasn’t that there were no disabled people in Russia. They were just hidden away. In America, they were visible.

Q: Was it hard to leave Russia?

Litman: When we decided to go, I was destroyed. In Russia, you never expect to move. There are not equal opportunities in other cities within Russia, so hardly anyone leaves the place where they were born. You expect to stay in the same neighborhood and have the same friends forever. Everything my life was built on was disappearing. It felt unimaginable to leave.

Q: How does your scoliosis affect you now?

Litman: It doesn’t affect me too much. Oh, it can be hard to find clothes that fit properly. There’s on and off pain, especially in winter, and if I stand on my feet more than 20 minutes, it takes its toll. I don’t do physical therapy any more, but I do a lot of swimming.

Q: Growing up in Russia, what was your impression of America?

Litman: In the early ’90s, they allowed one week of American TV per year. You could see “The Flintstones” and “Beverly Hills, 90210” and “Dallas.” It was kind of like, wow, there was this bright and shiny gloss on everything in that world. I was very much aware I cannot have that gloss, and did not know how to get that gloss.

I realized that it wasn’t that there were no disabled people in Russia. They were just hidden away. In America, they were visible. — Ellen Litman

Q: What was it like to be an immigrant, and start over in a new country?

Litman: The Last Chicken in America was about the initial immigrant experience. Immigration is really hard on your ego. Even the simplest conversation is hard. My English was barely serviceable, but it was the best in the family, so I had to make appointments and ask directions. Your whole sense of self and identity changes. It was incredibly hard on my parents. It felt like everything was breaking apart in various ways. Nothing felt normal.

Q: After college, you worked a number of IT jobs, in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and Boston. Were you also doing creative writing on the side?

Litman: Not at first, but I started taking writing classes at night at Cambridge Adult Education and then GrubStreet [a 20-year-old Boston-based creative writing center]. Julie Rold [a fiction writer and liberal arts professor at the Berklee School of Music] was the first person to say I had real talent. It was one of those moments that changes everything.

But writing was always a spare-time thing. I thought that maybe, if I got lucky, I could write part-time and do computer work part-time – but the value of what I was doing was edging out the computer stuff. And I was getting a lot of encouragement from teachers like Steve Almond [author of 10 books, including 2014’s Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto]. He’s wonderful. And so I decided to give myself a few years to really work on writing, and I applied to graduate programs.

Q: You attended the MFA program in creative writing at Syracuse University, studying with such luminaries as Gary Lutz, the poet and short story writer; and George Saunders, the MacArthur “Genius” Award winner and author of this year’s acclaimed Lincoln in the Bardo. How was that experience?

Litman: I got incredibly lucky! George Saunders became my thesis advisor, and he was generous to me, and to all his students. I learned a ton from his literature classes, and I learned how to teach creative writing classes too. He had a very intuitive approach to responding to students’ work, and to the energy of a class. He always talked about having respect for the reader. Think of your writing as if you’re driving a motorcycle, he’d say, and the reader is in the sidecar right next to you. You don’t want to condescend. The reader is an equal.

Half of us were doing traditional writing, half were more experimental. I’m more traditional. Gary Lutz approached language like a poet would. And the teachers all offered gentle encouragement if something could be improved in your writing, if each word was the best possible choice. I wrote the bulk of the stories for Last Chicken at Syracuse, and had the manuscript by the time I finished.

Q: How did you end up at UConn?

Litman: After I taught some workshops at Syracuse, I taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and also at Babson College in Wellesley, Massachusetts. After Norton published Last Chicken in America, I thought I’d see where it took me. The poet Penelope Pelizzon [associate professor, Department of English] was on the search committee at UConn. She was the one who really loved the book. She’s been my champion and mentor and supporter ever since. We went on to co-direct the Creative Writing Program in the English Department. It’s a really great program. It’s not a big program, but it’s found a lot of people whose work I admire.

I started here in 2007, before I had kids. And then when I had kids (Polina, 7, and Olwen, 3), I have found it to be a really supportive family-friendly environment. I love this place.

Q: Speaking of family, let me mention your husband, Ian Fraser. He’s a native of Johannesburg, South Africa, and was a playwright, fiction writer, and standup comedian there. How did you two meet?

Litman: On the T! We were on the Red Line in Boston. We both got on at Park Street and got off at Harvard Square. He was visiting America and asked if he was on the right platform, which started a conversation, and he asked if I’d like to go out on a coffee date. I said yes. He left for home the next day, but we emailed and Skyped, met in London, and were married six months later.

Q: In the book, Kat’s parents are dissidents. Were your parents dissidents, too?

Litman: No. My parents were part of a generation that had experienced many hard things, and they did not want to be involved. They were very cautious and needed to be cautious. It was ingrained in me, too, to be cautious.

But I did have these two charismatic literature teachers in my life, who I just adored. Anechka and Misha [Kat’s parents in the book] were a product of that. But once I had these characters, I couldn’t rely on my own experience so much. I was more well-behaved than Kat. My eldest daughter is very self-confident and will debate her teacher and ask for help. And I’m this mouse!

Part of it is that my daughter’s a product of where she was born, and I’m still a product of where I was born. In Russia, in my brace, I had to brace myself. I was pointed at. And anyone, at any time, a neighbor, a clerk, will yell at you for no good reason. In my day, rudeness was just part of the reality in Russia. Everything is state-run. There was no competition. Why be nice? It’s not like you’ll go to a different store.

Q: What are you working on now?

Litman: I’m in the middle of three different projects. One is a sequel to Mannequin Girl, with some of the same characters, set in the late perestroika years. Having lived with perestroika, I’m very much interested in how it shaped one’s political sensibilities.

But of course, corruption set in after perestroika, and eventually this led the way to Putin. In America, people may believe in a leader. I don’t think many Russians have that idealism.

In my Immigrant Narrative class now, we talk about how America is supposed to be the land of immigrants. But it’s never been equally accepting to immigrants, letting in European immigrants but not Asian immigrants in the past, for instance. My students can find this a revelation. With what’s going on in the news with immigration, every day, it all completely resonates with them now. And with me.