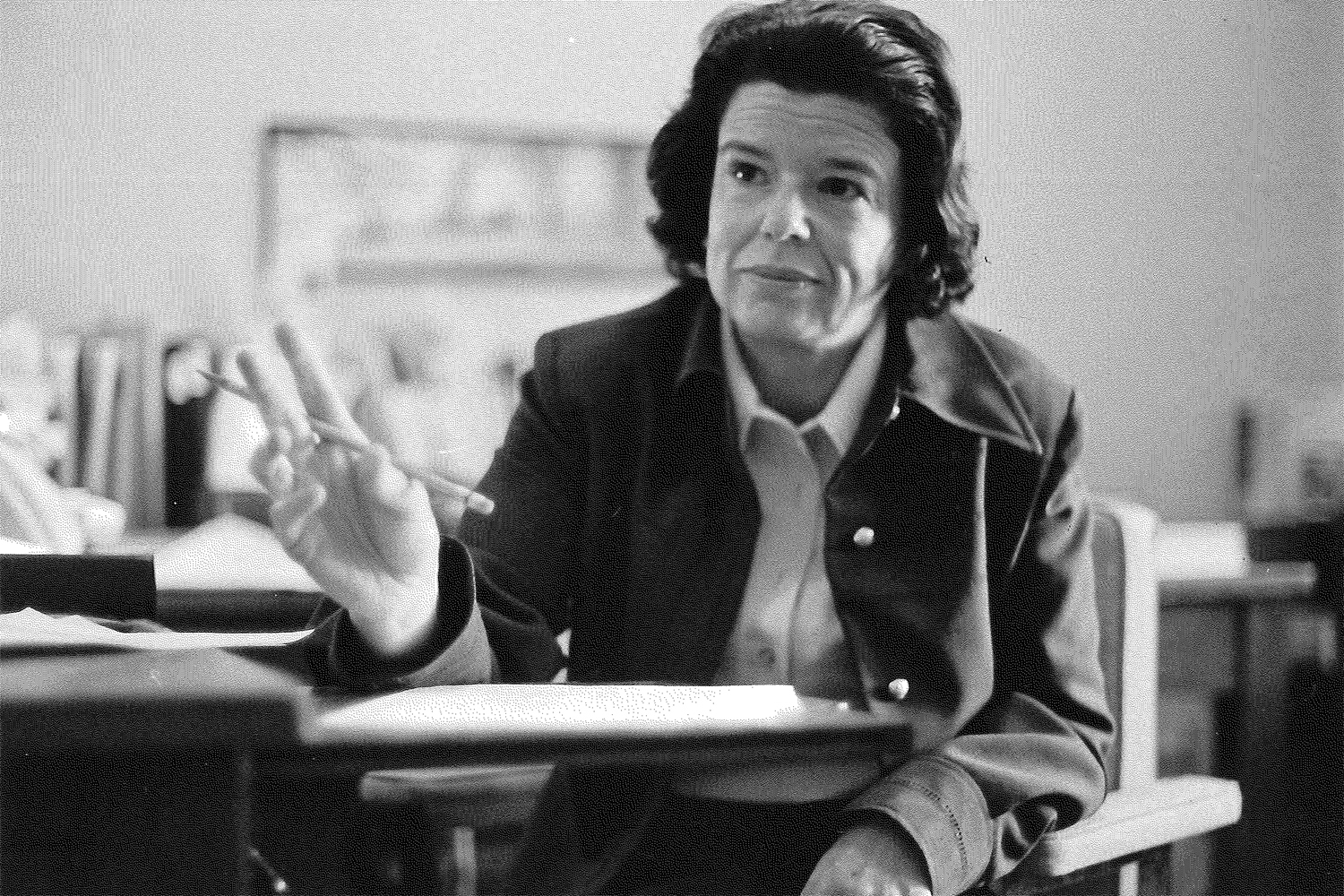

In these lean economic times, when state funding is being reduced for a broad range of projects and needs, one area where Gov. Dannel P. Malloy wants to significantly increase funding is linked to the research of Julie Robison, associate professor of medicine at the UConn Center on Aging.

The governor has proposed increasing funding for the Money Follows the Person Demonstration, a program that helps Medicaid recipients transition from institutional to community settings. Malloy’s proposal would provide $28.1 million in fiscal year 2012 and $57.7 million in fiscal year 2013 to transition more than 2,200 Medicaid clients from nursing homes to their own homes or other community settings.

Some of the most compelling evidence in support of community-based care comes from studies and quality of life surveys conducted by Robison and her research team. In the surveys, individuals moving from nursing homes to non-institutional settings are asked various lifestyle questions, such as how they like where they live, if they are treated the way they’d like, and how much choice and control they have over certain aspects of their lives.

Individuals are surveyed just before they move out of a nursing home, then again six months later, then again a year later. In the vast majority of areas surveyed, people indicated that they were more content outside of the nursing-home setting. They generally had fewer symptoms of depression and said they were happy with the help they were getting and the way they were living their life.

Because the individuals surveyed had willingly moved to a community setting, the results may be slanted toward non-institutional living, Robison says. Still, some of the statistics are striking. When asked if they liked where they lived, 25 percent of people questioned just while they were still in a nursing home said yes, compared to 85 percent questioned six months after they moved out of the nursing home.

Under Money Follows the Person, Connecticut receives an enhanced Medicaid match for individuals transitioning back to the community – reimbursement for 75 to 80 percent of costs for the first year back instead of the customary 50 percent. This federal support is a financial incentive to reduce the use of more expensive institutional care for Medicaid recipients. The approach is more cost-effective for taxpayers and is expected to lead to improved quality of life for older adults and people with physical and developmental disabilities and mental illness.

“The goal of Money Follows the Person is to rebalance the long-term care system,” Robison says. “The governor’s budget embraces this initiative. And our research shows that overall it looks like people are doing well in the community.”

In Connecticut, Medicaid long-term care expenses total almost $2.7 billion and represent the second largest item in the state budget, after education spending. Connecticut is joining other states in developing more programs that favor life in the community as opposed to nursing home placement.

Many people equate long-term care with nursing-home care, but it actually involves much more. Long-term care includes a wide variety of services that people may need because of an illness or disability, such as home health aides, visiting nurses, housekeepers, shoppers, meal services, and more.

One obstacle to this initiative, however, is finding people to work in the types of caregiving jobs needed by aging individuals and those with health needs. According to the Department of Labor, home-care jobs are the fastest growing in the field – but there are not enough workers to fill them.

Connecticut has established three regional Aging and Disability Resource Centers to help individuals and families navigate the system to find the best care option for their situation. For people who receive long-term care in the community, a care plan is built around the family’s availability and supports the family as caregiver. Services are added or modified depending on need.

This is not to say that nursing homes should be closing their doors. They are very much still needed for individuals with certain health needs as well as individuals with severe physical, intellectual, or mental disabilities. And many others may still choose to receive long-term care in a nursing home if they will feel it is the best option for them. But in order to adapt to the new transition initiatives, nursing homes might use their considerable expertise in eldercare to expand community-based programs, such as adult daycare programs or assisted living.

Long-term care is an important issue to older baby boomers as well as those taking care of elderly parents. “There are one million baby boomers – one-third of the population – and the oldest baby boomers just turned 65,” Robison says. “We’re seeing a big increase in the need for long-term care. The Money Follows the Person program has an opportunity in Connecticut to make some really good strides in rebalancing the system from institutional to community-based supports and services.”