The 16th century was a tumultuous time for religion in Europe. The Reformation divided nations, with Catholics and Protestants each pressing their desire for national dominance, and was further complicated by the rise of Calvinism in Switzerland and Lutheranism in Germany. Nowhere was the ideological divide more conflicted than England, where the nation’s religious identity changed three times within 25 years.

Religious conversion in England was by no means stable, with family histories dotted with differing religious affiliations through succeeding generations and questions about so-called “false conversion” – particularly about the Jews, who had been banished from the island nation – looming in the background of that time.

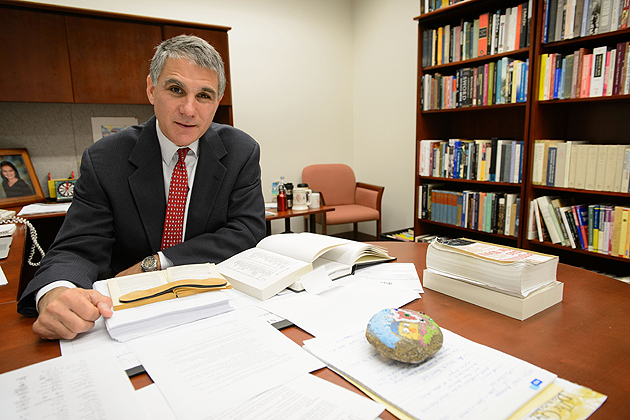

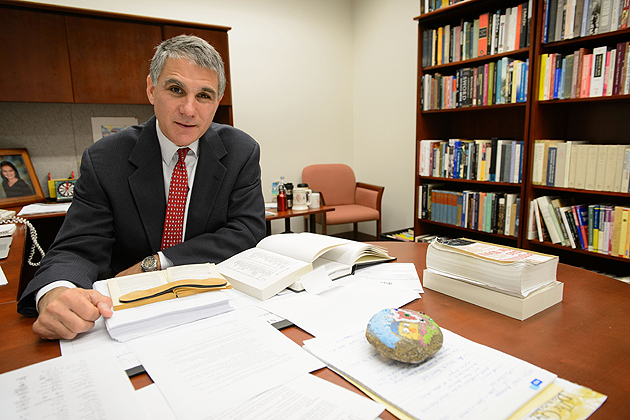

The idea of false conversion and accompanying concerns, which remained a threat to the desire for national unity in England through a common religion, is examined in a new book by Jeffrey S. Shoulson, director of the Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life and Doris and Simon Konover Chair of Judaic Studies, titled Fictions of Conversion: Jews, Christian, and Cultures of Change in Early Modern England (University of Pennsylvania Press 2013).

Shoulson, who is also professor of Literatures, Cultures and Languages and professor of English in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, says English uncertainties about authentic religious identity following conversion are reflected in 16th and 17th-century writings that reference the Jews, who had been expelled by King Edward I in 1290.

“The degree to which writers in 16th and 17th-century England give attention to Jews in that period, when no Jews were living in England, raises questions,” Shoulson says. “I was asking, why is there continued interest in Jews and Judaism, and is this interest related to how one defines a particular Christian identity?”

Religious identity and conversion

In Fictions of Conversion, Shoulson looks at John Donne’s poem “Satire III,” in which the poet struggles over his own conversion from Catholicism to the Church of England; and examines how issues over conversion were influenced through translations from the Old Testament to the New Testament and later, in 1611, the King James Bible; the resurgent interest in alchemy – the turning of base metal into gold – that was linked to Jews and their image, as reflected in writings such as Ben Jonson’s “The Alchemist” in 1610 and Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice,” circa 1597; and the nature of religious transformation in a period that was witness to the proliferation of numerous radical Christian sects.

Shoulson says religion finds its way into the writing of the time, even when it is not the main focus of the writing. “Religion is everywhere in this period. It kind of comes out in however different writers express themselves, even if they don’t necessarily set out to address a specific religious question,” he says. “For most of the early modern period [in England] the greatest art – whether poetry, painting, or music – was inspired or written within a particular kind of religious context. So much of that is grounded in some effort to express something about belief or religion, and to explore some of the larger meanings within those experiences.”

Throughout the Middle Ages, Jews were expelled from many nations, but eventually returned. In Spain and Portugal, for example, Iberian Jews who had previously lived under Islamic rule were forced to convert to Christianity when the region was gradually conquered by Christian forces, Shoulson says, noting that some Jews pretended to convert; doubts about false conversion ultimately led to the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 and the establishment of the Inquisition to root out these false conversions. The Jewish population became associated with religious deception and secrecy. When England expanded its mercantile interests and battled Spain over economic issues and naval supremacy, the English perception of Spain also became linked to its perception of Jews.

Cultural anxieties were projected onto the Jews as a scapegoat, Shoulson says: “We can look at all kinds of cultural anxieties emerging. One of the tendencies is to find some kind of scapegoated group in the community that cannot answer back. We see that today in the way American culture regards Islam as a kind of blank slate to project all kinds of anxieties. That happened during this period with Jews in England.”

The long history of Jewish exile and the later instances of forced conversion resulted during the Middle Ages in the emergence of rabbinical writings that raised new questions about the status of exiled Jews who converted, Shoulson says.

“You did have Jews who retained their sense of Jewishness. Many immigrated to the Netherlands,” he says. “A whole body of rabbinic literature emerges from that period about what the status of those people is, asking: When someone converts from Judaism to Christianity does it require that he reconvert back to Judaism, or is it as some insist, once a Jew, always a Jew? It produces a particularly intensive investigation into the question of Jewish identity within the Jewish community and outside of it. These are questions that have never left us.”