The partisan battles that have embroiled Washington for many years are most often about the proper role of government in the nation. Government is criticized from both sides of the political aisle – fueled by ideological sound bites – even as most Americans do not fully understand what government is supposed do, let alone what it actually does.

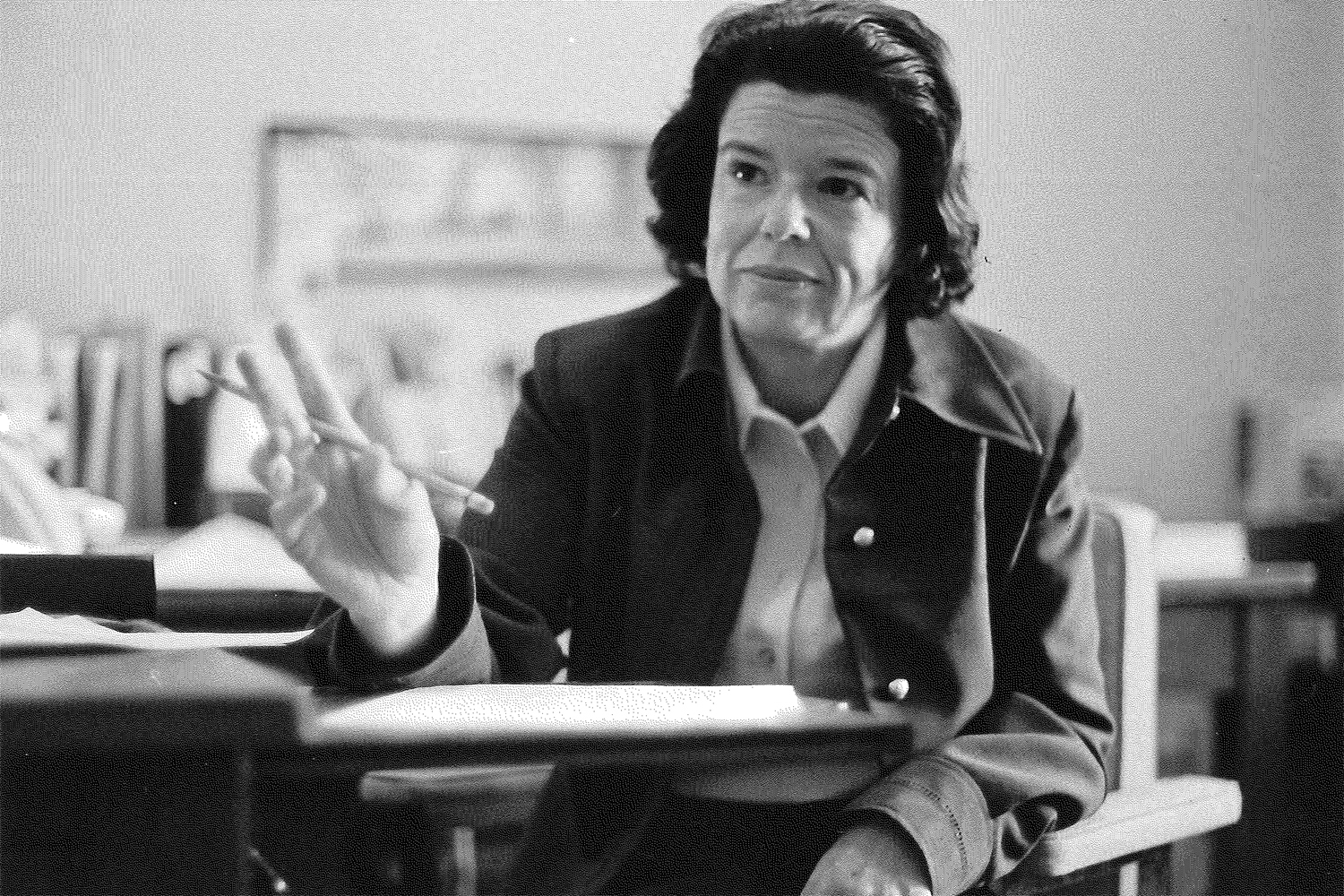

Brian Waddell, professor of political science at UConn’s Hartford Campus and co-author of What American Government Does (Johns Hopkins Press 2017), says if Americans better understood the function of their government the nation would benefit.

“I think this blunt fear of government doesn’t serve our nation well,” says Waddell. “Making Americans feel that their government is this enemy entity in their midst turns people away from politics, from wanting to engage in a progressive way with their government and get the government focused on things they want the government to do. We need to understand the positive and the negative parts of what government does, so we can act intelligently vis-a-vis the government.”

Waddell says most books about American government describe how it works rather than what it actually does. He and his co-author, Stan Luger, professor of political science and international affairs at the University of Northern Colorado, aimed to explain what government does.

Our government is a complex, multifaceted organization that engages in many different functions. Everyone can find something they like in what government does, and everyone can find something they don’t like. — Brian Waddell

The authors note that for nearly 40 years the political battle over the role of government has grown increasingly harsher largely based on a quotation taken out of context from Ronald Reagan’s 1981 Inaugural Address: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is our problem.”

In fact, Reagan was speaking about the lingering effects of the mid-1970s oil embargo by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Companies (OPEC), which caused gasoline and oil prices to skyrocket and led to a recession. These events led to high inflation and high unemployment, termed “stagflation,” and also increased federal debt. Later in the address, Reagan said: “Now, so there will be no misunderstanding, it’s not my intention to do away with government. It is rather to make it work – work with us, not over us; to stand by our side, not ride on our back. Government can and must provide opportunity, not smother it; foster productivity, not stifle it.”

Waddell says that while public opinion polls often show a mistrust in government, a 2015 survey by Pew Research Center found Americans think the government is doing a good job in several key areas of activity, such as responding to natural disasters, keeping the nation safe from terror, and ensuring safe food and medicine.

“Our government is a complex, multifaceted organization that engages in many different functions,” he says. “Everyone can find something they like in what government does, and everyone can find something they don’t like about what government does. Most people aren’t sure about what government does.”

According to Waddell and Luger, America moved from a nation that was largely managed through state and local government until the Civil War period in the mid-19th century. Later the economic devastation of the Great Depression in the early 1930s required the intervention of the Federal government, and resulted in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies that established an expanded welfare state. A decade later, World War II represented a national security crisis that brought about a re-orientation of the Federal government when the United States assumed global leadership in the post-war world, ushering in what the authors term “the national security state.” Although the military hero of the war, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, cautioned against establishing a “military-industrial complex,” the Cold War with the Soviet Union fueled just that, with the build-up of the defense industry. When the Berlin Wall fell, from the break-up of the Soviet Union, many thought there would be a standing down of the arms race. But the rise of international terrorism and the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., resulted in a reinvigorated national security state. The 2008 collapse on Wall Street again pushed government intervention into an economic crisis.

“We have a much weaker, less substantial welfare state than we would find in other countries. I argue that what we have in the United States is a warfare-welfare state; a strong warfare, weak welfare state,” Waddell says. “In commitment of society’s resources, the national security state is one of the single largest manifestations of government power the world has ever seen. When it comes to national security, very few questions are asked and there is very little debate or dissent. If you do dissent in debate, as I’m doing, your loyalty gets called into question.”

The authors point out that understanding the complex relationship between government and business also is essential to knowing how government functions. He says government and business are interdependent and develop in tandem with each other, with developments in the one sphere continually affecting developments in the other, making it difficult to point to a “free market” independent of government. An example he notes is the 2008 economic crisis that resulted from changes in regulating financial institutions that had been in place since the Great Depression, which led to the Federal government stepping in to bail out Wall Street companies.

Waddell says scholars who study business-government relations internationally have found that governments further removed from direct business pressure were engaged in policies that were better for the system as a whole than those who were very close to business.

“Businesses are very short-sighted. They want profits. In many ways, that’s not tenable over the long term because of the many problems that such a narrow focus produces,” he says. “Administrations that are more removed from direct business pressures tend to see the longer-term interest more ably and thereby serve business better than those who are much more directly involved and ruled by businessmen themselves, who are very short-sighted. They think when times are good, times are always going to be good. They don’t see trouble on the horizon that administrations who are removed from those pressures can act on.”

He says Americans should recognize that the private sector exercises power, most notably when a company that employs many people has a significant impact on a local community.

“It’s important that we understand it’s not only government that exercises power, private entities exercise power as well,” Waddell says. “When the government expands, it’s not a zero sum game that means society is losing power. We’re schooled in the idea that we get to be critical of government, to be skeptical and distrustful, and that this is what it means to be a good citizen. It’s ironic that we have this healthy skepticism about public power, which keeps public power constrained and within certain limits, yet we don’t have that same skepticism about private power.”