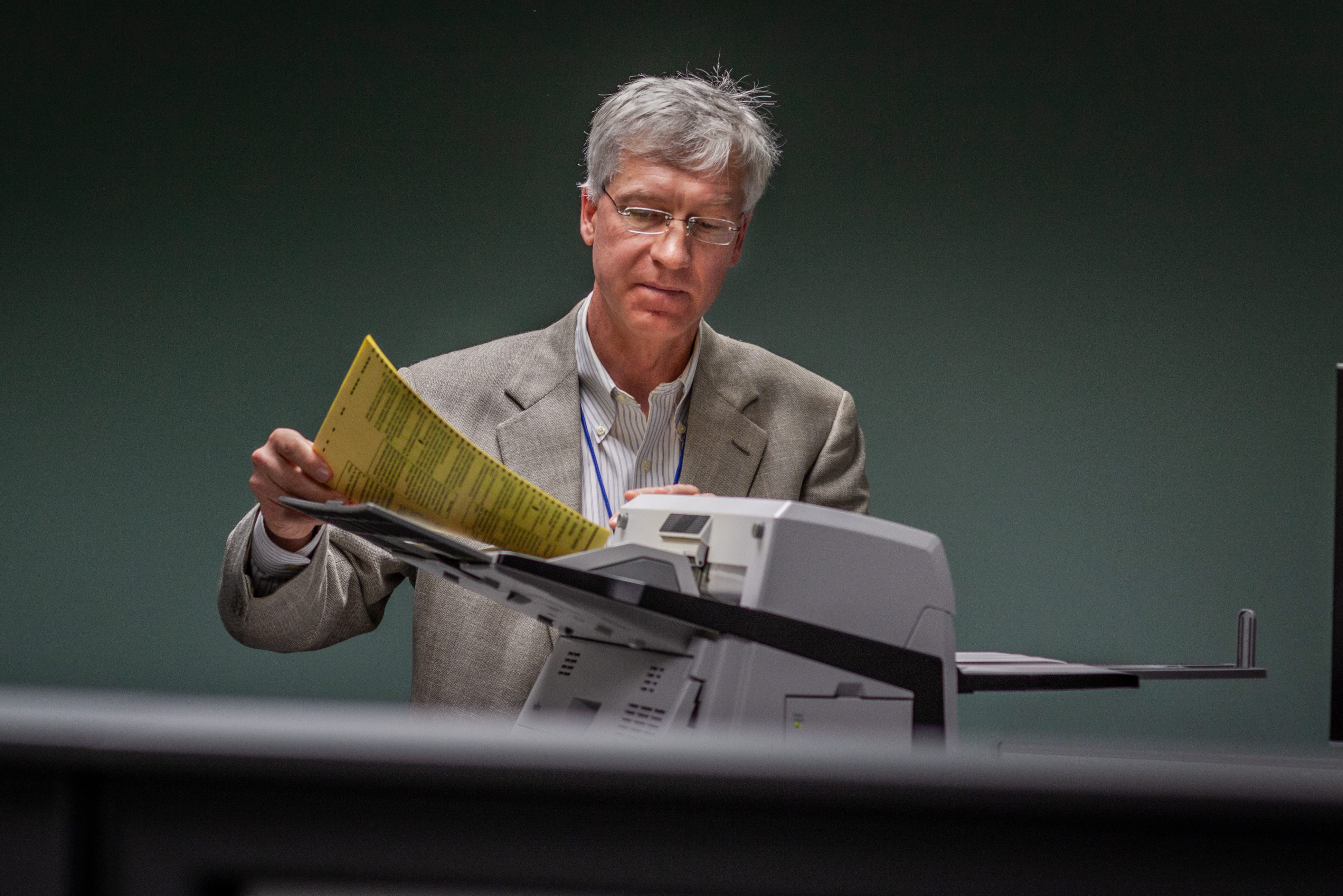

Both before and after the November election, the University of Connecticut will run forensic analyses on memory cards in the state’s voting equipment, deploying software to carry out audits of actual election results.

The need for this kind of expertise is pressing, especially with the growing threat that states experience from hackers. According to a recent Washington Post article, 21 states faced cybersecurity threats in the 2016 election, leading many states – including Connecticut – to strengthen their defenses.

This election, the work in Connecticut is being led by Alexander Russell, director of UConn’s Voting Technology Research Center (VoTeR), which advises the state on the use of election technology, investigates voting solutions and voting equipment, and develops and recommends safe-use procedures for electronic systems used in the electoral process.

Launched by the Connecticut Secretary of State’s office in 2006, the original vision for the VoTeR center was to advise the state on new voting technology, but that has expanded as technology – and the threats to that technology – has advanced.

“Of course, the most sensational attack against an electronic voting system is one which undetectably changes the reported outcome of an election,” says Russell, professor of computer science and engineering. “While the James Bond-appeal of these attacks elevates them to a common topic of conversation, the fact of the matter is that along the spectrum of various attacks those are comparatively difficult, expensive, and high-risk.”

Instead, the voting machines themselves need a human safeguard to ensure that the goal of the state to ensure the integrity of election results is foremost.

“One present difficulty is that vendors are primarily focused on functionality and ease-of-use rather than security,” says Russell. “In fact, we even lack clear standards for exactly what ‘security’ means for voting equipment.”

As a result, states cannot simply trust that vendors will provide “secure” devices, he says, creating the need for external security advice.

Steps like training voting staff in best practices, and teaching them what to look out for in terms of suspicious activity, are key to safeguarding the entire voting system, Russell adds. Connecticut has done a good job in these areas.

Connecticut also makes certain that optical scan tabulators are not connected to the internet, and that each town performs logic and accuracy testing before each election or primary, to ensure that the voting equipment and ballots accurately collect the votes and tabulate the results, he says.

“For the near future, the combination of voter-verified paper trails in conjunction with improving tabulators and audits will provide stronger security,” says Russell. “In the long term, cryptography can do amazing things, and I think we can expect to see completely digital elections with so-called ‘end-to-end’ security at some point.”