Although the Stop & Shop strike is over, that may not be the end to the tide of recent labor action. In the past year, there have been prominent teacher strikes across the nation, and here in Connecticut, a possible strike is looming among nursing home employees.

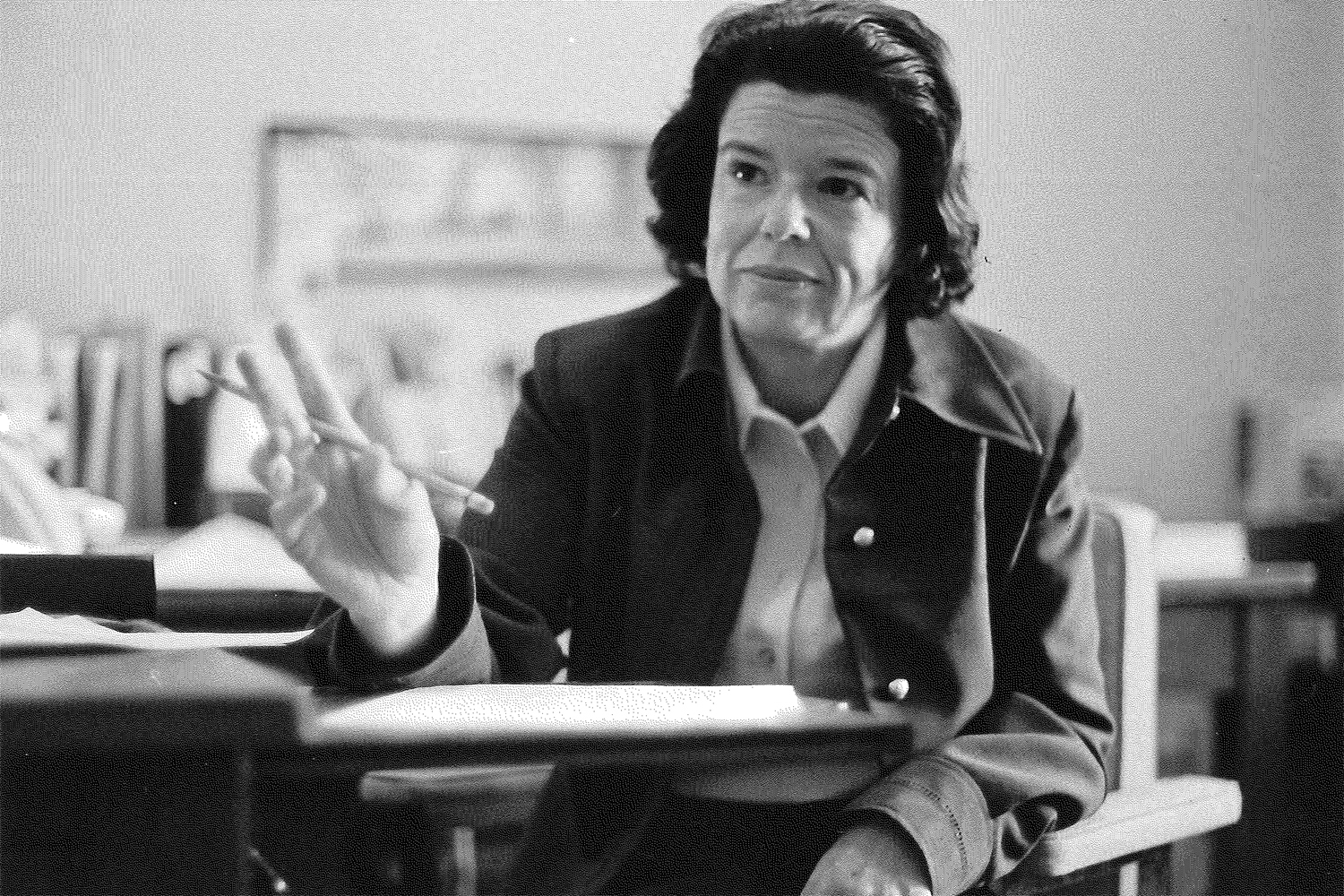

Management professor Nora Madjar shares her expertise on negotiations with UConn Today readers. Madjar teaches that subject to UConn undergraduate and graduate students, and also organizes an annual negotiation competition between law and MBA students at the University.

Q. Why are we seeing so many strikes today?

A. We have seen a huge increase in strike activities, from teachers to healthcare and hotel workers, since 2018. In some of these cases, the unions and their leaders played an important role and initiated the strikes, but in others it was not the union but the initiative of the rank-and-file, enabled by social media.

I believe there are a couple of forces going on simultaneously. The conventional explanation for the rise in strikes is that of a strengthening economy and tight labor market. In this view, workers are fighting to make up for income lost in the recession, and the ‘tight labor market’ means they are less afraid to take on the risk of striking. But there is a lot more to it than that. It is interesting to note that the services provided by the strikers – grocery store or teachers, hotels and hospitals – are local in nature and cannot really be exported, and this works in favor of the strikers.

In addition, the examples of successful strikes can be contagious and inspire the actions of others, and social media helps both in spreading the news and in organizing the workers. We now have many instances that show how direct actions can have an impact on wages, benefits, and even conditions that usually aren’t addressed in traditional collective bargaining. It’s a lot easier for the strikers to prepare and strategize with the additional information available.

In addition, the political climate may be conducive to this action. The Stop & Shop strikers, for example, attracted the attention and support of politicians from across the nation – a good way to increase their power. Social media and the support of politicians have helped them to prepare, gain confidence, and position themselves better to be successful in case of a strike.

Having said that, I believe that unions or workers do try to exhaust all other measures before resorting to a strike, for two reasons: union members usually lose money, and it’s the last thing that unions can do to get employers to agree to their terms.

Q. As a negotiation advocate, do you see strikes as a failing on the part of a corporation –or are there times when it’s just unavoidable?

A. In negotiations, the parties can choose from several different approaches and strategies: interests, rights, or power. Strikes are an example of a power strategy.

The recommendation is always to try to focus on interests, which means that the parties try to learn each other’s underlying needs, desires, and concerns, and find ways to reconcile them in an open negotiation. A focus on interests provides the opportunity to learn about the other parties’ concerns, priorities, and preferences, which is necessary for the construction of an integrative and mutually beneficial agreement that creates value for everyone involved. Although this seems like the most attractive and useful strategy for producing ‘win-win’ outcomes, the reality is that negotiations often become ugly and difficult, making the use of integrative strategies neither easy nor effective; and different sides then resort to using rights and power, and strikes may be one of the options for unions.

Focusing on rights means that the parties try to determine how to resolve the dispute by applying some standard of fairness, contract, or law. A rights focus is likely to lead to a more distributive agreement – one in which there is a winner and a loser, or a compromise that does not realize potential integrative gains.

Focusing on power, with strikes as a tool, means that the parties try to coerce each other into making concessions that each would not otherwise do. A power focus also usually leads to a more distributive agreement, and strikes, as one of the mechanisms for unions to exercise power, are typically reserved as a last resort during negotiations between the company and the union. It’s clear that both the union workers and the Stop & Shop corporation suffered pain during the 11-day strike.

That said, strikes are one way to gain power and exercise pressure in a dispute resolution when necessary – for example, when the other party refuses to come to the negotiating table or to recognize certain needs, despite significant efforts to encourage that party to do so. Or when negotiations have broken down, interests-based negotiation is exhausted, and the parties are at an impasse. A credible threat, especially if combined with an interests-based proposal for resolution, may restart the negotiations and lead to a successful outcome, as happened in the Stop & Shop case.

Q. Is there a point when you just need to take a rest from negotiations and take time to regroup?

A. Breaks are a very effective strategy for managing emotions and a useful tactics all negotiators have in their back pocket. A break may stop a downward emotional spiral. It may also help the parties involved to see the implications of their actions as well as the consequences of their demands or of a no-deal outcome. A lot of times, it is also easier to see the different perspectives and reframe the negotiation after a break.

The best negotiation outcomes usually satisfy the goals and interests of all parties involved. I believe that it is easier for one side to say ‘yes’ to what the other proposes when they see that proposal as a way to satisfied their own needs as well. This does not happen easily, and does not mean that all goals are satisfied through the initial proposal and positions offered. A lot of times, negotiators may reach the same outcome but in an alternative, creative, and mutually beneficial way, and not by just claiming a bigger piece of the pie.

Q. When two parties are far apart and there are bruised feelings on both sides, how does a skilled negotiator bring them to the bargaining table and establish an atmosphere that is conducive to compromise?

A. Negotiations are emotionally very complex, and parties may often find themselves reciprocating to threats with counter threats, escalating the negotiation to a standoff from which it is difficult or embarrassing to move toward any sort of workable solution.

The escalation of such conflicts, whether resulting in strikes, long lawsuits, paralyzing power struggles, or simply the frustration of not getting what you think you deserve, is associated with tremendous costs in time, effort, money, resources, and lost productivity. While the parties may be aware of the costs and the ineffectiveness of persisting with an obviously ineffective approach, it is very easy to become defensive, and get drawn into a downward spiral. Parties usually start to stubbornly insist on their position, instead of listening to the other side and being open to alternative solutions. As a result, they may find themselves completely unable to engage the other party to get what they want.

In situations like these, expert negotiators need to stop the reciprocation and bring the discussion from rights and powers back to the common interests – satisfied workers, happy and loyal customers, and a profitable company – or somehow motivate the other party to go back to the table.

To resolve a situation with a strike or a similar threat successfully, a pathway must be left for the other party to resolve the threat. In other words, there must be some way for the other party to save face and reopen the negotiations. A good way to turn off a threat is to combine the threatening rights-or-power communications with an interests-based proposal that indicates not only what you need in order to reach agreement, but also something positive that you are willing to do in order to reach agreement.

In the Stop & Shop situation, negotiations continued during the strike and the strike was used as a way for the unions to gain a more powerful position. It was interesting that May 1 – the date when company-sponsored health care coverage was going to lapse – was a pressing deadline that motivated the negotiations and the desire for a resolution from the unions as well.

Q. Is the ability to barter and negotiate a somewhat lost art?

A. My impression is that people are actually better prepared to negotiate successfully. In a lot of cases, they are more aware and informed that negotiations are possible and sometimes expected, and social media facilitates the dissemination of knowledge about successful previous negotiations. In addition, preparation and access to information, which enable better understanding of the full picture is key – with the internet and social media, individuals have a lot more information at their fingertips and can use it wisely in the process of negotiations in order to have a better idea of the whole context and all influential factors, as well as ways to develop alternatives and new strategies.

Q. What advice do you give your students to help them succeed in a difficult business or personal negotiation?

A. I usually emphasize three things proven to lead to better negotiation outcomes for everyone involved.

First: Prepare, prepare, prepare. Preparation is key for gaining confidence, understanding what constitutes a reasonable outcome, what is a good outcome, and what happens if you cannot reach a deal – this is a key criterion for assessing how good of a deal you have, what are your current or potential sources of power, and what is your bottom line.

Second, always try to understand and take the perspective of your opponent before making any offers or reaching a deal. Know what’s in it for them as well as for you

And, third, be firm on your goals but flexible on your positions or alternatives to achieve them – that is, be firm on the goals and needs you want to accomplish through the negotiation, and negotiate an outcome that satisfies them; but don’t be stuck on a position or one method for achieving them, be flexible and creative in the ways you accomplish your goals, be open to different alternative ways to satisfy your needs and create and claim a larger share of the negotiation pie.