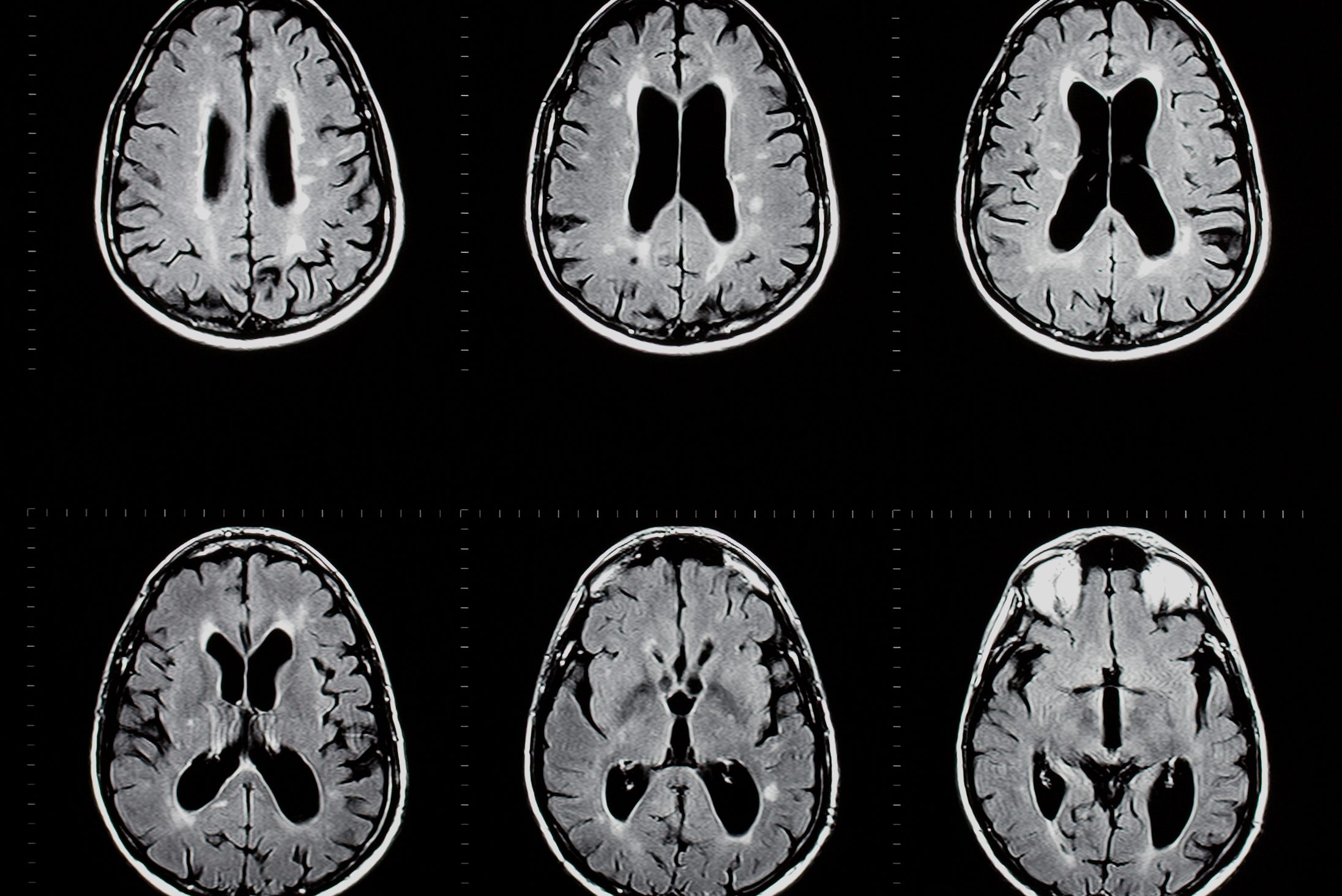

MS affects about a million people in the United States and many more globally. It damages the brain’s ability to communicate with the rest of the body, making it hard to walk, write or hold a fork and knife. This happens because of damage to the insulation around the nerves. Just like a frayed wire, a nerve with damaged insulation can short out or send bad signals. But the damage isn’t permanent, at least not at first. Most people with multiple sclerosis have recurring episodes of disability, followed by remissions when their symptoms lessen or disappear.

According to researchers, a molecule that helps blood clot may also play a role in multiple sclerosis relapses, as reported in the May 6, 2019 issue of PNAS. The research may help answer the mystery of why remissions happen, as well as find early markers of the disease.

The research also shows a new way to study multiple sclerosis (MS) in mice that is closer to the human form of the disease.

Why these relapses and remissions happen is a great mystery. We know that the damage to the nerves is caused by the immune system, the army of cells in our body that is supposed to protect us from disease-causing invaders. For some reason, in MS, the immune system turns on cells in the brain and spinal cord. In MS patients, a particular type of immune cell – CD8+ cells, a part of the immune system that normally kills cells that are cancerous or infected – seem to be the ones doing the damage.

Although researchers have been able to develop drugs to help fight MS using a mouse version of MS, these experimental mice develop a slightly different immune system response than what happens in MS in humans. Different cells do the damage in MS mice: CD4+ cells. The mice have CD8+ cells, but those CD8+ cells are generally quiescent. This has been a big stumbling block to understanding how the immune system develops in MS.

But a team of researchers from UConn Health, the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), and the Gladstone Institutes have figured out how CD8+ cells are activated in MS mice, and the result seems very close to what happens in humans.

The new findings hinge on how cells talk to each other. Cells will often secrete little bubbles containing proteins and genetic signals. These bubbles are called extracellular vesicles, or EVs. EVs are made by most cells in the body, and float in the blood stream like a message in a bottle.

So the team injected EVs from normal, healthy mice into mice that had that experimental MS-like disease. When they did this, the mice acquired a relapsing-remitting disease and active CD8+ cells, like human MS patients. The researchers examined the EVs in mice and patients with MS and found they contained fibrinogen, a protein that neuroscientist Katerina Akassoglou’s lab at Gladstone had been studying in MS. Fibrinogen normally helps blood clot and seal up wounds. But in these MS mice, the EVs with fibrinogen seemed to activate the CD8+ immune cells. When they injected the MS mice with EVs that did not have fibrinogen, they could not cause the relapsing-remitting illness.

“These findings expand our understanding of how fibrinogen contributes to the progression of MS pathology” says Akassoglou, senior investigator at Gladstone and professor of neurology at UC San Francisco. “Fibrinogen in exosomes may have far-reaching implications for therapies and as a biomarker for disease progression in MS and potentially, other neurological diseases,” she says.

“We now have a robust model of relapsing/remitting disease driven by CD8+ cells,” says UConn neuroscientist Stephen Crocker, who directed the study. “There’s all these clinically important questions we can now ask.” Crocker and his colleagues want to study this model further to understand how and why the remissions of disease happen.

“Understanding the causes of relapses is a key step on the path to a cure for MS,” says study co-author Ernesto Bongarzone, an anatomy and cell biology neuroscientist and professor at UIC. “The results of this study and the identification of fibrinogen as a key molecule contributing to relapses are exciting steps forward.”

The researchers would like to understand how the fibrinogen stimulates the CD8+ cells that cause the relapsing and remitting disease activity. They would also like to test whether fibrinogen and related proteins found in the EVs also play a role in humans with MS, and test if these molecular signals in EVs might be early warnings of relapses or disease progression.

Research in the translational relevance of these results is still ongoing. Over the past two years, UConn Health has developed a program for MS and Neuroimmunology care and research, under the direction of Dr. Jaime Imitola, MD, a MS neurologist and scientist. Imitola is an international authority in neural stem cells in MS; he works in progressive MS research, focusing on the role of immune cells in neurodegeneration and repair at the bench and the bedside.

“The results of Dr. Crocker’s project are still very much critical for MS patients, and the work in this research is ongoing,” Imitola added. “We know that CD8+ T cells can be directly toxic to neurons — the question is if this happens to patients, not just animals, and whether this is related to disease progression. Translating these findings to humans is the ultimate goal; UConn Health has an excellent environment for bringing research to the bedside.”

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Race to Erase MS, and the American Heart Association.