A recent UConn study, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), has found that a supportive housing intervention keeps more at-risk families together than “business-as-usual” child welfare services and costs about the same.

What’s more, a national study of five demonstration sites across the U.S. found that the Connecticut program produced the strongest child welfare outcomes across the country.

Preston Britner, professor of human development and family sciences, co-led the study, which was funded by a $5 million grant in 2012 from the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. DHHS.

The study, a collaboration among UConn, Chapin Hall, the Connecticut Department of Children and Families (DCF), and the non-profit housing group The Connection Inc., published its five-year findings in April.

“We had very strong findings for Connecticut families,” says Britner. “There are people in Connecticut that really need help, and they are really benefiting from this program.”

The Supportive Housing for Families initiative (SHF) began in 1998 in Middletown, Connecticut. State funds supported the non-profit social service agency The Connection Inc. in developing an intervention for parents newly involved with the child welfare system based on histories of mental health issues, substance abuse, criminal activity, or other factors.

The program’s premise is a “housing first” approach, says Britner, which assumes that families with stable, affordable, and appropriate housing are more likely to achieve success.

The SHF program includes organized case management with a dedicated case manager, mental health services, rental assistance and housing supports, and access to state or federal housing vouchers.

The program’s early success helped it expand into a statewide program, and in 2010, Britner, Farrell, and their colleagues published a report showing positive shifts in housing and environment of care for 1,720 families across the state.

That report attracted the attention of the U.S. DHHS, and in 2012 was one of two studies cited, along with a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-funded study in New York, in a call for a five-site demonstration project, called “Partnerships to Demonstrate the Effectiveness of Supportive Housing for Families in the Child Welfare System.”

“We had good evidence that the program worked, but it wasn’t an actual experiment,” says Britner. “The federal demonstration grant gave us the opportunity to study the effects of the program in a randomized control trial.”

In addition to Connecticut, the federal grant supported housing interventions in Broward County, Florida; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; Memphis, Tennessee; and San Francisco, California.

Of the five national demonstration sites, Connecticut was successful in stably housing families, had the most success in reunifying children with their families after placement in foster care, and had the highest rates of preventing removals to foster care, says Britner.

Compared with Connecticut’s standard child welfare services, families in both the SHF group and a further Intensive Supportive Housing intervention group had 20%-30% fewer child removals into foster care. Family reunification was also about 20% higher in the intervention groups.

An economic analysis reported that the interventions produced these superior outcomes for approximately the same cost as the standard child welfare model.

Two elements that Britner sees as crucial are a motivational interview approach combined with a scattered-site housing model.

[The non-profit asks clients] ‘Do you want to live close to family, to have help with child care? Or near work, so there’s less of a commute? Or somewhere else?’ It’s very client-focused and empowering. — Preston Britner

Motivational interviewing, which The Connection uses in Connecticut, involves sitting down with at-risk parents to understand what personally motivates them, and then pairing them with interventions, training, job opportunities, and housing that align with their interests and needs.

The program also works to integrate families with economic or social problems directly into functioning communities, rather than all at one site or building. Living among non-welfare families helps to motivate participants, says Britner.

This scattered-site approach is the subject of a forthcoming paper written by Britner with his Ph.D. student, Lindsay Westberg.

“The Connection really listens to clients and what their needs are,” Britner says. “They ask, ‘Do you want to live close to family, to have help with child care? Or near work, so there’s less of a commute? Or somewhere else?’ It’s very client-focused and empowering.”

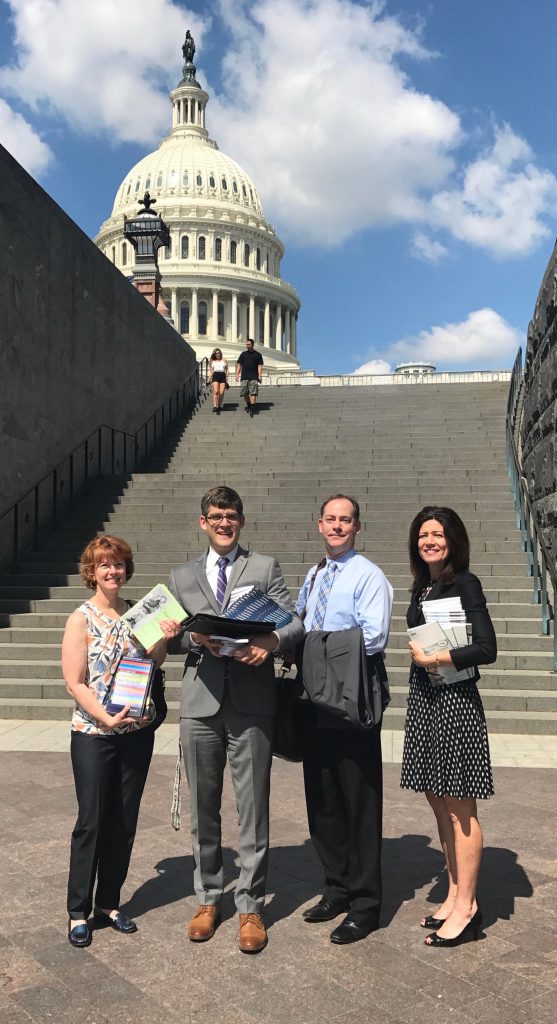

Britner and co-investigator Farrell, who was previously an associate professor at UConn and is now at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall – a policy research institution that focuses on child welfare and family well-being – developed testimony that Farrell shared at an April 2019 congressional briefing at the U.S. Capitol, and at a federal agencies briefing for executive branch staff.

Britner will also chair a panel including the other four demonstration sites in August at the National Child Welfare Evaluation Summit in Washington, D.C. The local models had successes in Florida and Tennessee, but less success in Iowa and California.

He hopes elements of Connecticut’s 20-year commitment to supportive housing can help improve outcomes at these other sites, which have only been using the approach for five years.

“Here in Connecticut, we have a mature program that’s been around for a long time,” he says. “Housing is tougher in other places. Many landlords don’t want to take housing vouchers, even though that’s discriminatory.

“We hope our team approach – with DCF, UConn, Chapin Hall, and The Connection – can help other places achieve the trust we’ve established,” he adds.

Britner plans to continue to testify at the state and federal level that programs like SHF should be expanded to the federal level.

“There are very few of these types of projects out there like this one,” he says. “As a researcher, putting in 20 years on something, and refining a successful project like this one, feels very good.”

This video, produced by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, showcases the supportive housing program that Britner’s study reviewed: