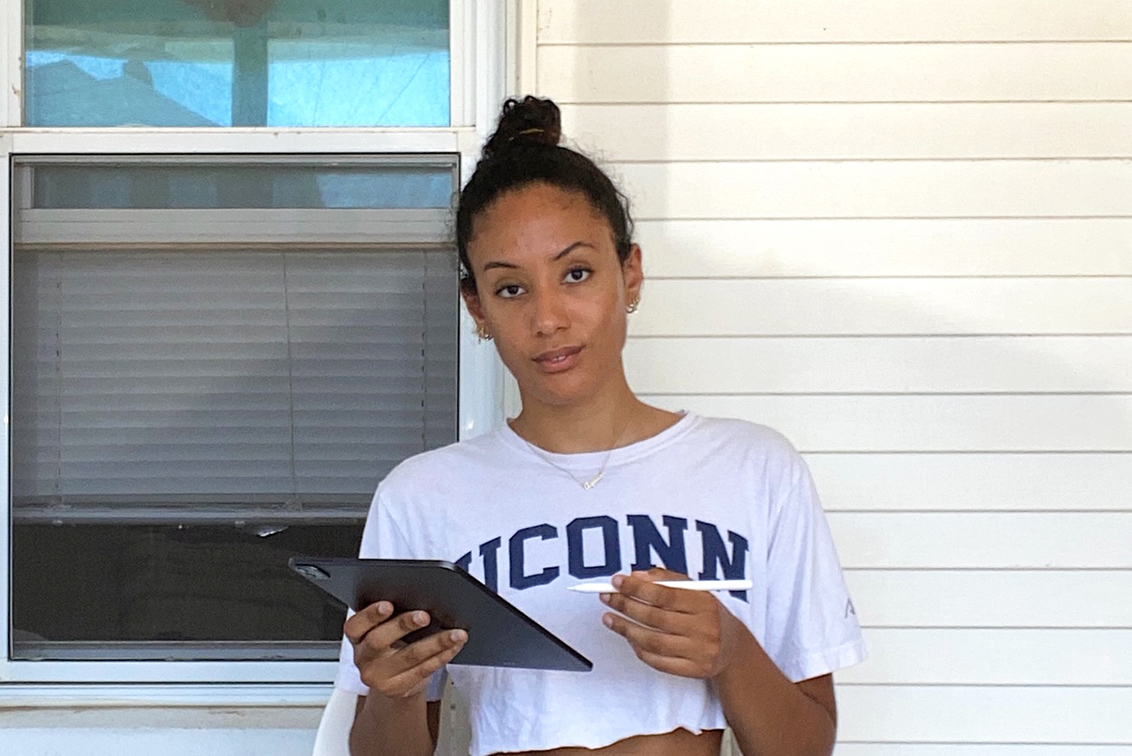

Aquia Providence ‘21 (CLAS) loved her research routine. For three years as an undergraduate in assistant professor Julie Fosdick’s geoscience laboratory, she got to examine samples of four-billion-year-old rocks. And she was crushing it.

“I could do rock crushing, which is where you crush rocks in a metal bowl with your hands, or I could do gold panning, like they did during the gold rush,” Providence says.

After crushing and sifting through grains of zircon and apatite minerals, she assessed the quality, sorting out microscopic grains if they had been damaged in the process. Then, Providence would put the sample on a tray with alcohol solution, don a lab coat and special eye cancer-blocking goggles, and test the rock in a helium thermochronology laser.

The test would help to determine how old the rocks, which came from along major fault lines in California, are. Understanding their age will help scientists better understand earthquake activity.

“When I was a freshman, I came almost every day in the summer, and I would do that process for eight hours a day — and I loved it,” she says.

But when the coronavirus pandemic caused colleges to transition to online-only classes, Providence lost access to her samples, and had to figure out another way to study what she loved.

This summer, she and other CLAS student researchers overcame obstacles posed by the pandemic to continue their research and produce results by adapting their methods to working from home.

Alexandra Frenzel ‘21 (CLAS), a marine science major, has been researching genetic diversity of zooplankton, planktonic organisms that are vitally important to the ocean’s ecosystems.

As an undergraduate in Professor of Marine Science Ann Bucklin’s lab, Frenzel did a lot of benchwork, which involved extracting zooplankton DNA, putting DNA material into tubes to make copies, and generating DNA barcodes for various zooplankton species.

Similar to barcodes on items in a store, DNA barcodes help to identify species by their unique label.

“I have been more interested in smaller organisms at the base of the food webs because not only is the ecosystem structure built on them but they also play vital roles in biogeochemical cycling in the oceans,” she says. By studying the microscopic ocean life, she learns more about the dynamic components of the ocean as a whole.

“We had fresh samples, and I would have done lab work before doing the analysis steps, but we had to change the whole plan,” she says.

Without access to her samples, Frenzel had to switch her thesis entirely, pivoting to a more accessible dataset.

Instead of plankton, she’s now exploring gene expression in beluga whales from a dataset provided by Connecticut’s Mystic Aquarium. The data demonstrate differential gene expression from two different populations of beluga whales, one from a more pristine ocean environment northwest of Alaska, and one from an area with a higher surrounding human population, and therefore greater external stressors.

“My research trajectory has changed a lot since COVID-19 because I’ve delved way deeper into computer programs than I previously would have,” she says.

“It sucks to not be able to be in the lab. But I don’t think I would have dedicated as much focus to understanding what’s going on behind the screen of the analysis if we weren’t forced to be online.”

The University began a phased reopening for undergraduate research in July, and by the end of the month about 40 requests to return, including CLAS students, had been approved. But many students elected to continue working from home.

“I’ve tried my best to make a home office where I set up my computer and have my books and notes,” says James Kolb ‘20 (CLAS), who is continuing his research through Greenhouse Studios, a joint effort of the School of Fine Arts, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and the University Library.

“I sit here and work, hours will go by and I don’t even notice. Then it’s 3 a.m.”

Ordinarily, Kolb would conduct his research at the Homer Babbidge Library, making use of their archives and computers.

Since working remotely, the history major with a double minor in geography and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has learned new methods of finding and using digital archives for his research on migration and housing among the Black, Puerto Rican, and West Indian communities in Hartford, Conn.

He and his research advisor, Fiona Vernal, associate professor of history and Africana studies, are trying to get an accurate picture of Hartford in the 20th Century to track the migration of those communities as housing changed in the capital city.

“These early Black communities were clustered close to railroads, on floodplains, and in places rejected by others as desirable residential sites,” says Kolb. “We’re trying to map what affordable housing looked like over time, and how housing projects changed that layout.”

Kolb spends hours digging through historical records and creating mappable datasets by geocoding addresses from various decades. At one point, his slow personal laptop wasn’t enough to handle coding up to 30,000 addresses, so he had a custom computer built.

“I was concerned about the lack of face-to-face contact, because what I do is so visual and getting feedback on maps over the phone is much more difficult,” Kolb said.

Now, he texts images of archives and the maps he is working on with questions to Vernal, who provides timely responses.

Because their research is largely qualitative, students in the humanities and social sciences say they’ve been fortunate to lose little time on their work.

Joshua Lovett ‘21 (CLAS), (ENG), is pursuing dual degrees in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and chemical engineering with an English minor. He received Summer Undergraduate Research Funding to explore constructions of loneliness as presented in English literature, targeting 19th-Century Victorian literature, modern adult fiction, and youth loneliness in young adult literature.

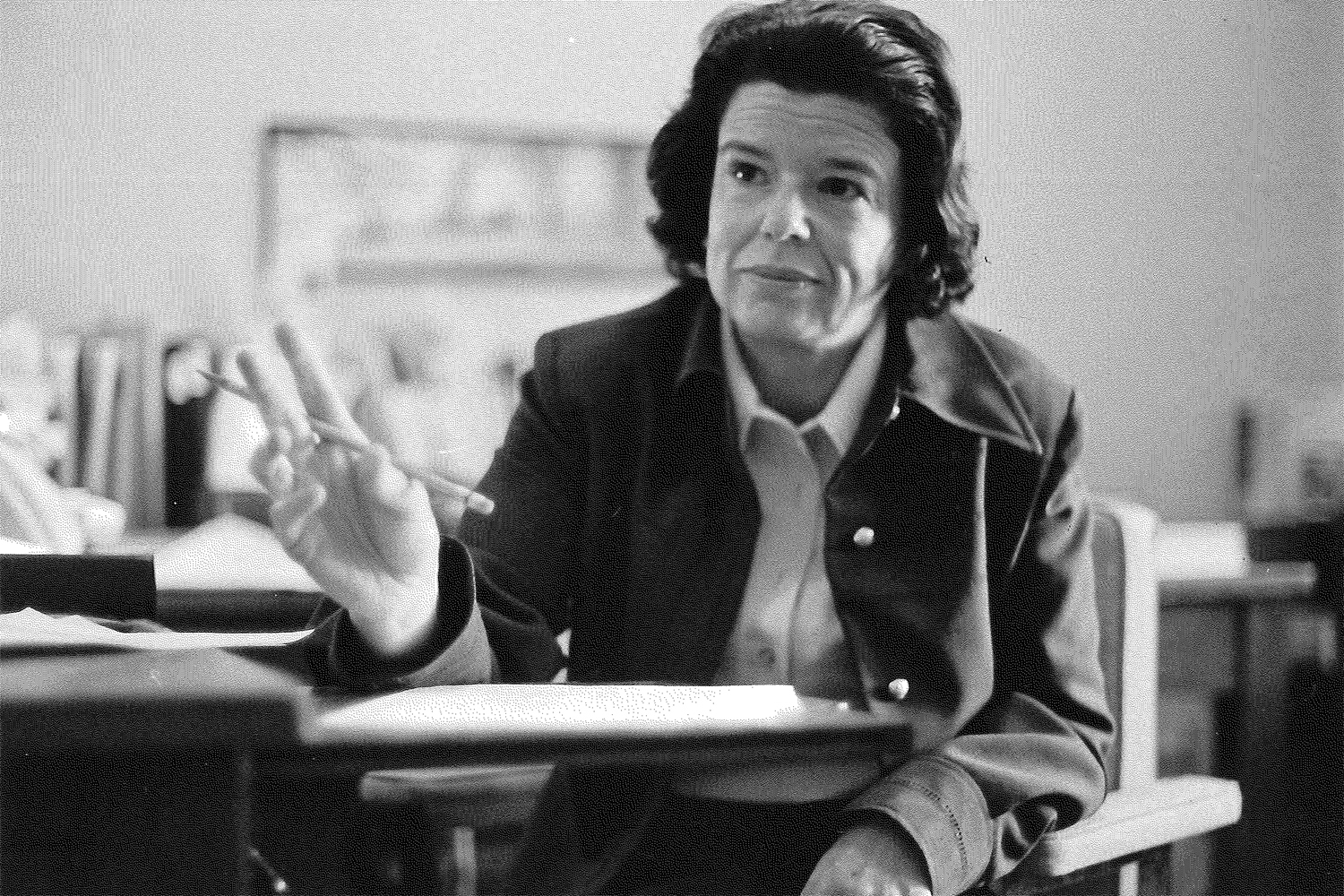

The idea came from wanting to work with Board of Trustees Distinguished English Professor Gina Barreca.

“She taught a class on loneliness in literature and I took that. I’ve adapted (my research) slightly to include books about the pandemic,” he adds.

Now, Lovett is analyzing loneliness in Frankenstein and Silas Marner, because he noticed loneliness as a student in the engineering program, and because he wants his findings to inform psychological research on loneliness in the future.

“Authors are keen observers of character and many psychological studies today confirm observations made by authors even hundreds of years ago,” he says.

“They might see people who internalize loneliness are more likely to feel ashamed when something tragic happens and try to investigate it. There may be no hard data on that, but they may see my publication as a starting point to explore it.”

Providence, meanwhile, overcame tactical obstacles by helping to make their work accessible to other scientists. As a SURF awardee, Providence is discovering why and how ancient samples of apatite rocks along the San Andreas border in southern California moved over the past eight to nine million years. Her work could help scientists better track and predict movement along the active fault line.

Her project uses a helium thermochronology laser to date the rock samples by quantifying the timing of erosion rates and uplift along the southern San Andreas border fault. As the designated operator of the laser, Providence felt “very scientific” every time she used it.

“Basically, I have six samples of rock—three from one area, and three from another area. At some point in history, these samples were buried underground, and the hypothesis is that they originated in the same area,” she says.

Now, she wakes up at her family’s shoreline house in Clinton, Conn., reads other graduate students’ theses or literature reviews, and enters coordinates on her apatite rocks from Coachella, California into a massive geoscience database called Geochron.

“When I enter the data on my rocks into Geochron, I see my work pop up on the shared map, which is very satisfying,” she says. The data she enters shows up as a yellow dot over Coachella, California.

“I stay motivated by thinking about the end goal,” Providence says. “Eventually I’d love to be a professor. I think this is a stepping stone, just one hill that I have to get over, and now I know how to adapt to doing research at home.”