Perhaps it was growing up on the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya where every afternoon, Richard Anyah watched huge cloud banks build into thunderstorms. Perhaps it was the influence of an early mentor, who became the head of the national weather service. Or, perhaps it was the example of his father, a community leader, who championed education for his seven children. It may be that all of these experiences, blending like a weather system, are what led Anyah to Storrs, Conn.

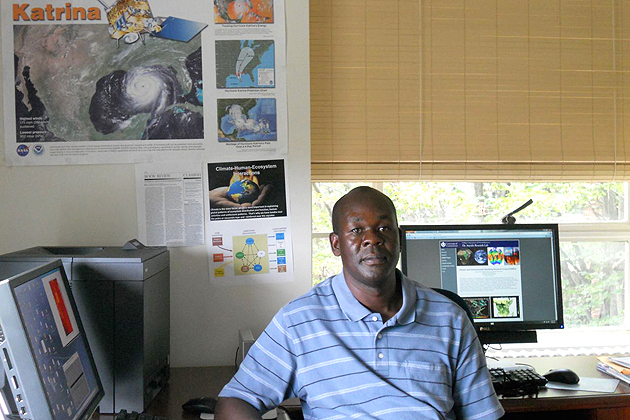

An assistant professor of atmospheric sciences in the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Anyah holds a BS degree in meteorology from the University of Nairobi and an MS and Ph.D. in atmospheric science from North Carolina State University. He is a soft-spoken man, committed to teaching others about climate and the impact humans have on it.

Anyah is a scientist with a philosophical streak. He developed a strong foundation in mathematics and physics in elementary school. In high school, he excelled at advanced work in the hard sciences. Once introduced to meteorology, which combined his interests in math, physics, economics, and their interaction with human beings, Anyah knew he had found his niche.

He trained as a high school teacher and taught math for two years in a secondary school in Kenya. He now calls on the skills he developed as an instructor as he directs the work of his undergraduate and graduate students at UConn.

Anyah considers fundamental questions that drive aspects of climate and environmental changes. He looks at environmental issues and attempts to find ways to help society deal with constant change.

“Human beings usually don’t acknowledge change even though they recognize that things around them are changing. They will say that what is happening in the environment isn’t new. When you tell them what humans are doing is contributing to the change, they say ‘no’,” says Anyah with a wry smile.

Anyah was drawn to the study of climate science as a way to create understanding between the effects of weather and society. He asks his students to look at the effects of climate on water resources, ecology, and air systems. Through the use of numerical modeling with computer systems, they can look at vast amounts of data representing longer periods of time.

By working with data from centers all over the world, students are able to analyze how slight changes in temperature affect entire systems. Work is done in collaboration with centers in the U.S., Europe, and Africa to study processes that influence the predictability of regional climates and climate change and to apply that information to understand the drivers of climate-human-ecosystem interactions.

By looking at data from the past 100 years, students are able to chart trends and measure the effects of change on surface water, crops, diseases, invasive plants, and other facets of human existence that on the surface may not seem immediately tied to climate.

Modeling Climate Variability and Change

Since 2008, Anyah has worked with three graduate students and four undergraduates from different departments on a National Science Foundation grant, Modeling Climate Variability and Change in the Greater Horn of Africa. He is clearly excited about the project, which looks at climate data generated by global and regional climate models and then analyzes and highlights patterns in the past, present, and future climate systems over the Greater Horn of Africa and their relationship to natural and human systems.

While accumulating and working with vast amounts of data on climate is intellectually compelling to Anyah, his work helping students develop their own potential as scientists is equally engaging. He sees the NSF-funded Research Experience for Undergraduates as a way to build a platform of competency that will carry them much further in their academic careers.

He notes that one former graduate student is pursuing a Ph.D. at a prestigious institute, and an undergraduate’s work has been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Anyah believes research should be relevant to society. While acknowledging that climate has become a buzzword and a focus of alarm, he understands that there are still uncertainties. There are changes, and people need to know how they will be affected. A course he teaches called Climate-Human Ecosystem Interactions, which looks at the big questions, including the element of uncertainty, attracts students not only from the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources but from other UConn schools and colleges as well.

“I’m very proud of my students,” says Anyah. “They are very smart. This program has become a breeding ground for graduate students. Another benefit is that they have been drawn from other departments within the University. They come to our college and become deeply engaged in the research process and discover they like it.”

Climate change is often portrayed as negative, but Anyah has a more balanced perspective. Long-term trends point to great variation in climate and a dominant fluctuation toward warmer temperatures, which if understood, can be managed, he says. Warmer temperatures may lead to new invasive species, types of pollen never before seen, and even new pests, but Anyah doesn’t see those as totally negative.

“The Northeast may get prolonged growing seasons – perhaps two cycles instead of one,” he says. “It could have a positive aspect if society can adjust.”