They may be picture books meant for the youngest audiences, or story books for those honing their reading skills. Fairy tales or adventure stories. Science fiction or mysteries. Poetry, too. Whatever the genre, books written for young readers are an important literary form, no less meaningful than those works that are written for adults. Terri Goldich will tell you that, and she should know.

As an undergraduate at UConn, Goldich majored in German language and literature and she subsequently earned a graduate degree in library science. In 1996, she was working at the Homer Babbidge Library when the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center opened its doors, and she decided to make the trip across the courtyard for the position of events and facilities coordinator in the new building. Two years later, she became curator of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. As such, she holds the key, literally and figuratively, to the books, illustrations, and correspondence that are stored in carefully climate-controlled facilities at the Center.

The collection is maintained for the benefit of students and researchers and, in some cases, the authors themselves, who want to know their efforts are not only appreciated in the present, but will be available for study in the future.

The Collection Begins

“Our collection of children’s literature really began in the 60s,” Goldich says, “with a donation from author and illustrator Nonny Hogrogian, who gave about 600 volumes of 19th- and 20th-century children’s books to us.”

In the 1980s, the collection benefitted from the generosity of Billie M. Levy, a librarian and the wife of UConn Law School professor, Nathan Levy. “She had a basement full of books which she donated, about 8,500 volumes, and at her urging the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection was created.”

Goldich also says that UConn owes a great debt to former professor of English Francelia Butler, who died in 1998 at the age of 85. It was Butler, an early champion of writing for young people, who founded the Journal of Children’s Literature in 1972.

Upon Butler’s death, a eulogy published in the Arts section of The New York Times described her as: “a late-blooming academic of such passionate, unorthodox ways that she has been credited with almost single-handedly transforming the study of children’s literature from a stepchild of library science into a recognized academic discipline.”

According to Goldich, Butler’s courses on children’s literature were among the most popular on campus, and celebrated figures such as esteemed baby doctor Benjamin Spock, Sesame Street’s Big Bird, and actress Margaret Hamilton, who played the Wicked Witch of the West in the film The Wizard of Oz, were recruited to speak to her classes.

It was Butler’s stamp that put UConn squarely on the map of children’s literature, and while she donated her personal book collection to Hollins College, the sponsor of her journal, UConn holds her extensive collection of papers; a gift from her daughter.

Special Effects

The Northeast Children’s Book Collection is especially noted for its emphasis on authors who live in the Northeast. Among them are Barbara Cooney of Maine, a double Caldecott winner for Ox-cart Man (for her illustrations) and Chanticleer and the Fox, and Tomie dePaola who wrote and illustrated Strega Nona, which was a Caldecott Honor Book, and Christmas Remembered, among others. He was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts degree from UConn in 1999.

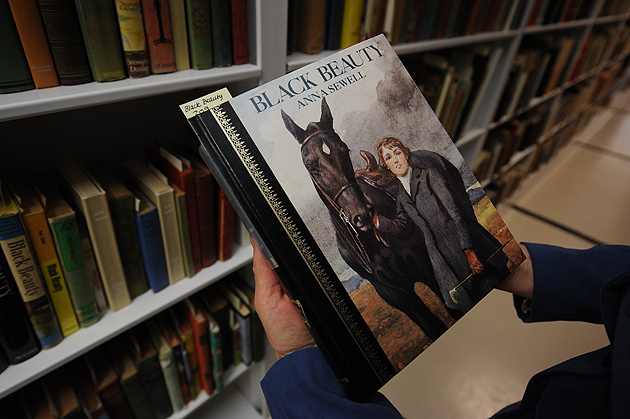

But in an interesting turn of events, the collection also holds one of the world’s foremost collections of Black Beauty, written in 1877 by English author Anna Sewell.

As to why the book has remained continuously in print for over 125 years, Goldich says, “I think one of the hallmarks of a classic is that it has to work through time, it has to work through language so that it doesn’t lose anything in translation, and it has to work through cultures. The story of this horse and its trials and tribulations is obviously as germane to somebody in a foreign country as it is here and in England. It lasts because the story has universal appeal.”

The Dodd Center is home to about 450 different editions of Black Beauty, including one first edition from England and two American first editions. There are also two Braille editions of the book in the collection.

Illustrating a Point

One of the things that sets children’s literature apart from most books written for older audiences is the use of illustration, all of it designed to enhance a child’s reading experience and much of it carefully nuanced with a level of sophistication that gives it lasting appeal. The collection holds many examples of this, including the five mock ups, or ‘dummies’, of Mouse Match that author/illustrator Ed Young created before settling on a finished product; the nine successive ‘dummies’ that Anita Riggio did when illustrating her own book, Smack Dab in the Middle; and examples of Richard Scarry’s ‘blue board’ technique that he used when transferring illustrations from original sketch to finished product.

In cases where author and illustrator are not the same, Goldich says, the two will most often be kept apart. “It’s the publisher’s job to make sure that the author’s words and the illustrator’s vision match. It’s not always the easiest thing to do, but in the end, it works.”

As to the popularity of ‘old fashioned books’ in the ever-expanding age of electronics, Goldich cites the most recent Connecticut Children’s Book Fair that was held on campus in November:

“At one point we were hip-deep in four year olds, and judging from the looks on their faces when they walked into the room filled with books, it’s very difficult for me to believe that the children’s book is ever going to go away.”