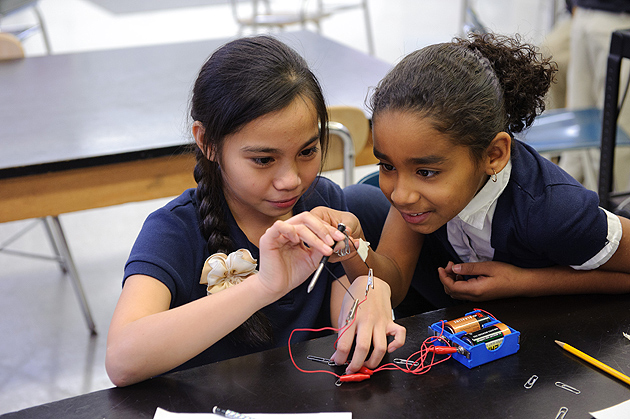

The brightly lit room is a-buzz. Groups of three or four children, all fourth graders, sit or stand around small tables, trying mightily to create an electromagnetic current that will lift more and more paper clips. Their teacher, Freddie DeJesus, wanders from table to table, sitting and chatting and making suggestions to help move each group in the right direction.

Le’Lah Arthur loves it.

“This is a really fun place,” says Arthur, referring to the sparkling new Renzulli Academy on Cornwall Street in Hartford, the first stand-alone, public school academy for gifted and talented children in an urban area in the country. “They let us a do a lot of really fun things.”

Her friend, Aleigha Johnson, agrees.

“I really like it here. It’s much better than my old school,” she says.

The academy is a dream come true for its founder, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Education Joseph Renzulli, a nationally and internationally known champion of gifted education, and his wife, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Education Sally Reis, both faculty members in the Neag School of Education. The two have spent most of their careers trying to make legislators and school districts recognize the importance of challenging the best and brightest students to reach their full potential.

“The fact that the city [of Hartford] has recognized what we’re doing – they gave us the building, rehabbed it, gave us the space, the equipment – great computers and smart boards, and allowed us to select and train outstanding teachers – is a testament to their commitment,” says Renzulli. “It makes it much easier for the teachers to do their job.”

Perhaps even more important, the Academy provides the teachers with much more stability than typical in-school gifted programs, which often go away when a grant expires or a new superintendent moves in. Here, Hartford’s education budget follows the students: so as long as the students continue to live in the Hartford school district, the city will be paying for them one way or another. And, according to Miriam Morales-Taylor, assistant superintendent for learning and support services, this is where the city and board of education want these students to be.

“We’re changing the stereotype of Hartford students,” says Morales-Taylor. “Nearly 25 percent of our students are now in magnet schools, charter schools, or academies, and we’re limiting enrollment in those schools to no more than 500 students, so they can receive direct education.”

The Renzulli Academy, which opened its doors two years ago in various corners of the Simpson-Waverly School on nearby Waverly Street and moved into its new quarters this fall, currently houses 104 students in grades 4 through 8. The plan, adopted unanimously by the board of education, is to add a kindergarten and 9th grade next year, 1st and 10th grades in 2013, and so on, becoming a K-12 school for gifted and talented Hartford school children by 2016. The school will have a maximum enrollment of about 300 students, hailing from all corners of the city. Reaching that level should not be a problem, says lead teacher and director Ruth Lyons.

“Unfortunately, we had to cap 5th grade enrollment this year,” says Lyons. “Parents are clamoring for information but, to do what we want to do, class sizes must be limited.”

The growth I’ve seen in these kids has been remarkable.

It’s no wonder parents are anxious to enroll their children at the Academy. The classes are small, and most of the mainstream schools among the 49 in the city are forbidding blocks of buildings, dark and unwelcoming. Waverly Street, where Simpson-Waverly School is located, is lined with overgrown scrub brush and covered with litter, all in sharp contrast to the refurbished academy, which sits on a tree-lined street, a black wrought iron fence surrounding the property, which features a grassy entrance area and playscape. The interior of the building is no different. Light streams into the building. The floors sparkle. Everything smells clean.

And the children at the Academy are scrubbed clean, too, neatly outfitted in their uniforms – blue shirts and khaki pants or skirts. Best of all, they are excited, chattering, working. A social studies class darts into the hall, posting the reports they just wrote on Abraham Lincoln, Illinois, and other historical topics on one of a number of 4’ by 8’ boards that line the halls. In a history class, hands pop up when the teacher asks questions about how soldiers in the Civil War survived the misery of encampments, and how Confederates and Union fighters handled the conditions differently. In between question periods, the students perform, acting out aspects of their studies.

“The growth I’ve seen in these kids has been remarkable,” says Lyons. “Especially the students who had a rocky start. They’ve really turned a corner. And the students who were solid when they arrived are even better. They have so much curiosity, so much potential.”

Lyons says the Academy, using Renzulli’s methods, is also like a research laboratory. In fact, she is listed on her business card as a research assistant, watching carefully to see how the students react to an advanced mathematics curriculum called Mentoring Mathematical Minds (Project M3) developed by faculty in the Neag School of Education. They teach advanced reading skills using research led by Renzulli’s partner, Sally Reis, the Schoolwide Enrichment Model – Reading Framework (SEM-R), an enrichment-based reading program that allows students to choose what books to read, as long as they are challenging and above grade level. Teachers in SEM-R don’t lecture from the front of the classroom, but mingle with the students and discuss what they’re reading individually. And the science curriculum is based on the scientific method and meets daily, unlike many other schools.

“We’re putting research into practice,” Lyons says.

The school day is also longer than in other districts, running from 8:45 a.m. until 4:15 p.m. Classes are held in 70-minute blocks. And the students get homework that matches the rigor of the classroom, not the watered-down versions in many public schools, where teachers must focus primarily on the students who are lagging, leaving the bright students to work on their own.

“Homework can be a challenge to a lot of these kids, who are used to being able to knock it off on the bus ride home,” says Lyons. “That isn’t the case here. They’re working one to one-and-a-half grades above level. They’re used to being a big fish in a little pond, and now they’re little fish in a big pond.”

Recognizing the workload, one of the requirements for admission to the Academy is for the parents to sign on, to agree to support their child, provide a positive home atmosphere, and devote time to working with them.

“That isn’t always easy,” Lyons says. “A lot of these children are living with a single parent who may be working two jobs, who has child care issues. Sixty-five percent of our students are on free or reduced lunch.”

There are other rules, both for the city and the students’ families, whether in Hartford or any other district interested in adopting the Renzulli model – officials from Waterbury and New Haven have visited, as have representatives from a city in Texas and a faculty member from a school district in Australia.

“The district has to agree to pay all expenses and guarantee they will adhere to gifted pedagogy,” says Renzulli. “Training of teachers – they have to know the pedagogy of gifted education. They all have to sing out of the same prayer book. There must be good leadership. We have that here with Ruth [Lyons]. And third, I want people [who visit] to serve an internship, at least a week, not just a drive-by. They have to internalize the spirit of what we’re doing.”

Academy Receives Grant for Summer Enrichment Program

With a $250,000 grant from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, the Renzulli Academy will establish a summer enrichment program for its high potential/low income students.

The academy will use the grant to establish a six-week summer program focusing on art, science, and math, followed by an independent or small group project.

“One of our greatest challenges is helping all of our students have a background and context in which to understand big ideas in literature, history, geography, mathematics, and science, so they can apply this knowledge to challenging academic work,” says Renzulli.

The program will begin this summer for students in grades six, seven, and eight, and will expand over the next two years, so it is available to all the students.

“This grant will allow the academy to broaden the horizons of our students,” says Academy director Ruth Lyons.

The grant from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation is renewable for up to three years. The Lansdowne, Va.-based foundation helps exceptionally promising students reach their full potential through education.

The seven teachers at the Academy have that spirit. Three are UConn alumni with degrees in education. Lyons is currently completing her dissertation as a graduate student in the Neag School of Education, and should have a Ph.D. from UConn by May. Another, Melissa Thom, also is a current UConn student in the Three Summers Program in gifted education, also run by the Neag School.

As more teachers are hired, they will first be screened by Lyons and Renzulli, and then recommended for hire by the school district. They will be employed by the Hartford school system.

The students applying must score at the very top of the Connecticut Mastery Test; submit an essay and a teacher’s recommendation; and include a letter from their parents that, among other things, entitles Academy officials to scour the student’s records, not just for academics but for disciplinary issues as well, and evidence of creativity and perseverance.

“It’s a talent pool approach. It’s not just test scores. We look for students who have potential,” says Lyons, “students who will be ready to attend an elite university and obtain a challenging fulfilling job.”

By the looks of things on Cornwall Street, that shouldn’t be a problem.