Medical staff is trained to keep an emotional distance from patients. But for interpreters of deaf and hard-of-hearing patients, who follow patients through every step of their hospital experience, it can be very challenging at times to keep their distance.

“We are nationally certified with a strict code of conduct and ethics that we are charged to follow,” says Leslie Warren, a sign language interpreter at the UConn Health Center. “But in a hospital, navigating the extremes of birth and death, your human ethic sometimes becomes the more guiding force.”

From the time a deaf patient enters the door, the interpreter is there during the registration process, treatment planning, questions for the clinician, appointment scheduling, and discussions with other departments. The interpreters are available throughout their stay, up until the time the patient is walking out of the building.

In some hospital settings or physicians’ offices, deaf patients may be forced to wait for an interpreter to be called or the medical staff relies on the use of video relay interpreting. Video relay is a computer system that connects a deaf patient with a sign language interpreter over the internet. This new technology has several downfalls and has been met with limited success in the deaf community.

“The wait can be tough for both the patient and clinician. Without an interpreter, things easily get dangerously confusing,” says Warren, who started her career as a teacher at the American School for the Deaf.

UConn Was First

Warren joined the UConn Health Center in 2003, making John Dempsey Hospital the first hospital in the state to hire a full-time staff sign language interpreter.

Maranda Reynolds, a registered nurse, soon joined Warren. Reynolds says she developed an interest in sign language at age 5 while watching an episode of “Sesame Street.” She was mesmerized right from the beginning and started to learn about the language before she even met anyone who was deaf.

With the establishment of consistent, reliable language access, the number of deaf patients coming to the Health Center for treatment continued to grow, and UConn hired its third part-time interpreter, Lydia Pantoja. They now serve about 600 deaf patients.

Distinct Language

American Sign Language is a distinct and unique language unto itself with its own syntax and grammatical features. Some of those features include body stance and positioning, eye gaze, and facial expressions that are critical to the message in addition to the actual sign mechanics, Warren notes.

Warren says that lip reading is often not reliable for those who are deaf. Only about 30 percent of words can be understood through lip reading because words look so similar when spoken. Words like shoes, choose and juice, and phrases like “car accident” and “heart attack” can all look the same on the lips.

On the Move

UConn’s three interpreters are always on the move, traveling around the hospital and to satellite locations. Reynolds says it is not unusual for them to come in at odd hours of the night or on weekends.

“There’s not another job quite like it,” says Reynolds.

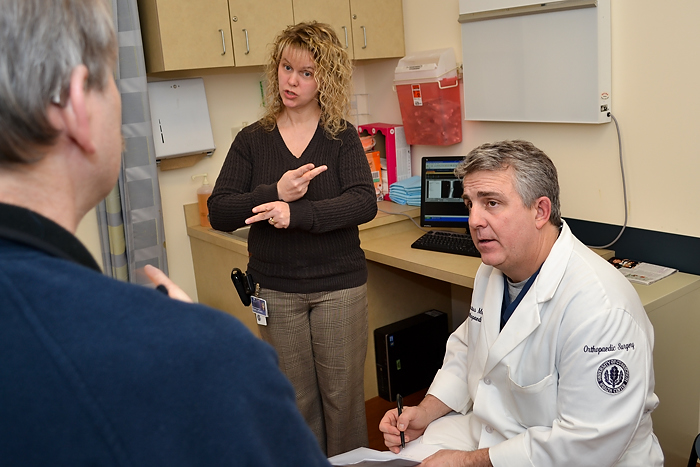

The interpreters must constantly adjust to any and all medical situations, says Warren. Sometimes the interpreter must move around in cramped quarters or twist around medical devices to make sure the deaf patient has full visual contact, insuring uninterrupted medical communication access for the patient and health care providers.

Reynolds says the interpreters have a great relationship with the doctors. If there is not an interpreter readily available for an appointment and the patient says he or she will be fine without one, the doctors will often insist that an interpreter be present.

Unique Bond

Warren and Reynolds say that their bond with patients is unique from that of most doctors and nurses because they have served many of their patients for years, across all medical specialties.

They are there to help expecting moms through their entire pregnancy – from prenatal care, to labor and delivery and then pediatric appointments. But they are also the ones looking in patients’ eyes telling them they have a terminal illness.

“We’re not doctors, but we ‘hear’ the information first and then must accurately interpret the medical information to the patients, regardless of circumstance,” says Warren. “It can be very difficult to emotionally separate yourself from the situation at times, especially when the news is not good. We’ve all shed tears.”

While their work can be difficult at times, it is also extremely rewarding.

“I never imagined I would be in this field,” says Warren. “You land where you are supposed to be.”

Follow the UConn Health Center on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.