Law school dean Jeremy Paul is a guest contributor to UConn Today. His posts appear on Thursdays. To read more of his posts, click here.

Business and government leaders are blue-faced from talking about how the United States needs to expand education in math and science if our country is to remain economically competitive. Perhaps, however, some public comfort with higher mathematics may be even more crucial to improving our civic life. That’s because public understanding of contemporary policy choices too often hinges on seeking simple solutions via minimizing or maximizing one purportedly relevant number. When that number is poorly chosen or when no such number could suffice, building mathematical literacy will help us ask key questions that might revitalize our democracy.

Consider recent views about changing housing patterns in Connecticut presented at our Law School last month. Demographers explained how Connecticut’s population is aging and how this will render remote suburban housing increasingly dysfunctional. Smaller residential units adjacent to transit centers have proved successful in other states, particularly when parking facilities are re-located away from the transit station. Yet one roadblock to residential construction in the urban and suburban core is that costs per square foot are often higher. As long as potential residents compare rents or real estate values between inner and outer suburbs, developers may be reluctant to invest in the housing that experts say is most desirable.

Our presenters explained further, however, that savvy consumers should look beyond housing prices to minimizing the more important figure combining housing expenses with commuting costs. As gasoline prices rise, making long commutes more expensive, housing in the core ought to be more attractive. We all know, however, what a challenge it is to create a combined statistic (housing plus commuting) in the public mind. Perhaps we might locate the public health specialist who taught us to distinguish good cholesterol from bad and ask him or her to market what involves little more than elementary mathematical grouping.

Persuading people to combine two numbers into one, however, is child’s play compared to truly exploring one of America’s deepest articles of faith: trust in the bottom line. We have created the most successful economy in world history by creating organizations large and small devoted to the single aim of maximizing profits. We love how this unequivocal goal settles arguments about proper institutional direction, and how it enables us to hold our leaders accountable. We count on competition among firms to drive people to better performance and console ourselves that focus on a single number will create peak efficiency. When profits cannot serve as an adequate measure, we invent surrogates such as U.S. News & World Report rankings.

The rudimentary mathematics required to understand whether profits have gone up or down, however, will prove insufficient for the complex challenges that lie ahead. Of course, things have never been all that simple, because profit maximization has a short-run and long-run component. Should I pay my workers less, reducing expenses now, or pay my workers more to keep them happy over the long term? The tension between short- and long-run profits provides crucial flexibility for management to make sensitive judgments, while simultaneously keeping everyone focused on a single bottom line. Who could argue with a complex system that retains the appearance of maximizing a single value?

The stark reality of contemporary life, however, is that our most pressing challenges involve pursuing seemingly contradictory goals. We need to increase economic growth, while also conserving natural resources. We need to fill key positions by relying on measurable talents and accomplishments, while understanding the importance of redressing historical inequities. We need to encourage investment and creativity by protecting intellectual property, while fostering experimentation and progress by preserving freedom to use the building blocks needed for research.

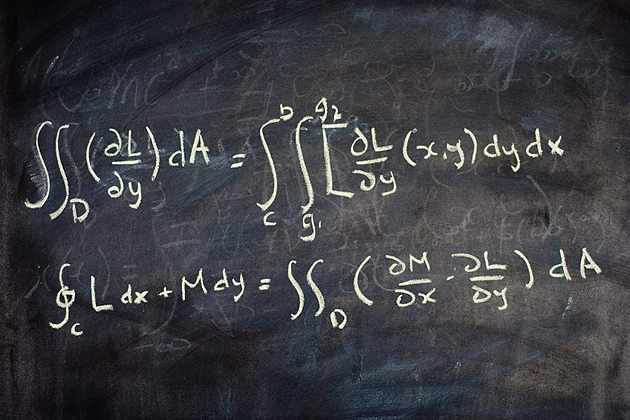

All our basic instincts that equate accountability with choosing one direction or another (are you pro-growth or pro-environment?) take us back to a vision of maximizing a single variable. Wouldn’t it be marvelous if we instead had a vocabulary that allowed us to place a premium on maximizing more than one variable at a time and that enabled us to identify ideal combinations of competing variables? Our public discourse is at a loss, but our friends in the math department have a name for this. They call it calculus, and we need to start paying attention.