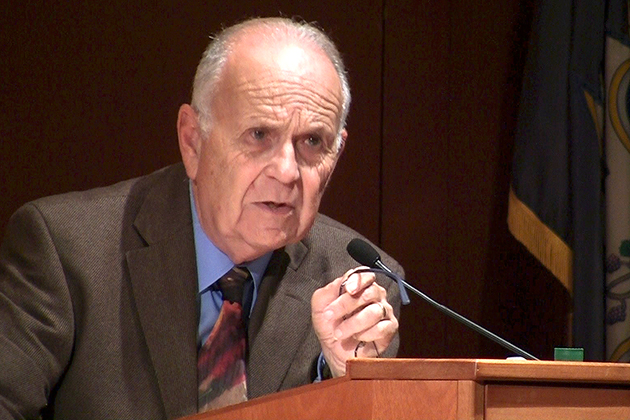

Higher education pundit and New York Times columnist Stanley Fish makes no apologies for his views on the subject of academic freedom.

Often, he says, faculty take the concept too far, extending it to “freedom with a capital F.”

“Some agendas abandon the adjective ‘academic’ and focus instead on the word ‘freedom’,” said the distinguished university professor and professor of law at Florida International University, speaking in Storrs on Friday. “In these cases, the freedom being exercised springs free of any academic constraints.”

In a talk titled “Versions of Academic Freedom: From Professionalism to Revolution” hosted by the Humanities Institute and the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Fish described a continuum of opinion on academic freedom at universities in the United States. He believes in a strictly professional definition, in which freedoms are limited to the prescribed duties of teaching and research, and not to any other campus activities.

On the other hand, he said, many faculty take academic freedom as “permission to start a revolution.” His talk sparked an animated debate, with several dissenting opinions.

Some agendas abandon the adjective ‘academic’ and focus instead on the word ‘freedom.’

Academic freedom gives university faculty the right to decide what they want to study and teach and how they want to study it and teach it. In the U.S., the concept was first explained in 1915 in the American Association of University Professors’ “Declaration of the Principles of Academic Freedom and Tenure.”

Unlike other sectors of the workforce where superiors dictate an employee’s work, academic freedom comes without interference from a university’s administration or other outside standards – because the results of academic work can’t be known in advance.

“There’s a zone of freedom that is recognized in the classroom and in research activities,” Fish told the crowd in the Dodd Research Center’s Konover Auditorium. “The problems occur when faculty members don’t see that distinction.”

During the discussion, attendees questioned the issue as it relates to disciplines such as philosophy, gay and lesbian studies, and political science.

Thomas Long, associate professor-in-residence in the School of Nursing, said that when he taught at another university, he was asked to prepare a signed statement about the content of his class in sexuality studies. He claimed the request was unfair treatment and violated his academic freedom.

Fish recounted examples of academic freedom violations that have reached the courts, such as a professor turning a class into planning meetings for social protests, and another outlining in an email to his students his belief that current-day Israel is worse than Nazi Germany.

But several professors pointed out that comparing current-day political confrontations with those from the past is a valuable teaching tool, and that despite their most earnest efforts, political science faculty can sometimes let their opinions slip into their teaching.

Despite its various definitions, Fish asserted that academic freedom is invaluable, and that faculty should not have to defend universities as worthy of this “special treatment.”

But when you’re forced into a corner, he said, and there’s no escaping justifying your academic work?

“Hire a PR firm,” he joked. “Or get yourself some good lawyers.”