Some of the nation’s top experts in computer hardware security gathered in Storrs this week to discuss new ways to thwart a growing international counterfeit electronics industry.

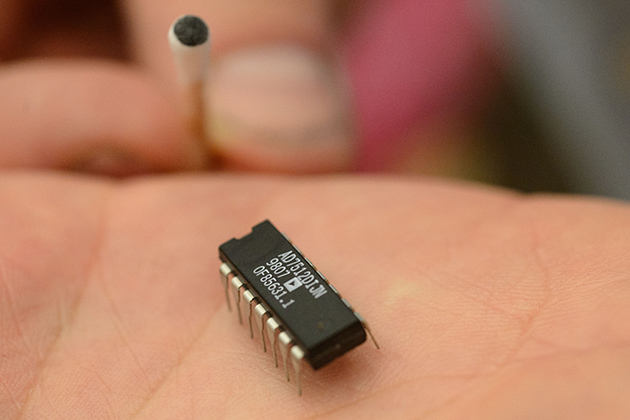

Reports are increasing of recycled and cloned computer chips making their way into the electronic component supply chain that threaten the integrity of everything from cell phones and personal computers to medical devices and the weapon systems of military fighter jets.

In a series of workshops on Jan. 28 and 29, engineers from Intel, Texas Instruments, Analog Devices, Honeywell, the Missile Defense Agency (MDA), and Connecticut-based SMT Corp., as well as other entities, discussed new tools for improving detection in the increasingly advanced – and profitable – world of counterfeit electronics. They also discussed ways to stay one step ahead of the counterfeiters through the development of low-cost technologies that would stamp unique “signatures” on hardware components to ensure that only reliable, high-quality parts are available to manufacturers.

The two-day symposium was sponsored by UConn’s new Center for Hardware Assurance, Security, and Engineering (CHASE) and the U.S. Army Research Office (ARO). Mohammad Tehranipoor, UConn’s Castleman Associate Professor in Engineering Innovation and director of CHASE, was one of the event’s organizers.

Tehranipoor has been working on electric hardware security and cybersecurity threats for more than nine years. He describes the threat of counterfeit integrated circuits as a ticking “silicon time bomb.”

“This is a very challenging problem that requires a suite of solutions, as well as a strong collaboration between academia, industry, and government to tackle it,” says Tehranipoor. “UConn is leading a lot of the effort in this domain.”

Most counterfeit circuits are brought in from independent suppliers overseas. They are packaged as new, but may be damaged or used. The tampered chips are pulled from scrap circuit boards and other electronic waste and altered to look like their fresh, factory-made counterparts. The problem with counterfeit chips is that they are unreliable and can wear out prematurely, Tehranipoor says.

There is a growing concern that these chips could be embedded with malicious Trojans, allowing third-party access to sensitive personal or government information. The chips also are capable of being loaded with electronic “kill switches” that can be engaged remotely in order to disable or hinder a system’s performance – the last thing you want to happen when you’re piloting a $50 million fighter jet at 1,000 mph in wartime.

U.S. Rep. Joe Courtney (D-2nd District) attended the conference on opening day, taking time during his presentation to praise UConn’s leadership in conducting research vital to national security. Courtney, a member of the House Armed Services Committee, told the audience how impressed he was with the enormous amount of electronic components involved in the operation of the U.S. Navy’s Virginia-class submarines built in Connecticut and docked at the U.S. Submarine Base in Groton.

”These systems are as important to our national defense as the people trained to operate them,” Courtney said. “One malfunction can cause a massive amount of damage in terms of human life. Making sure these systems are safe is incredibly important.”

A Senate Armed Services Committee report issued last year found more than a million counterfeit electronic parts were used by the Department of Defense between 2009 and 2010. The parts were identified as coming primarily from China, with the remainder originating in the U.K. and Canada. Congress, in response, passed strict new anti-counterfeiting requirements for defense contractors that impose stiff penalties for those who fail to comply.

“This is the future, making sure these systems operate correctly,” Courtney told the engineers at the conference. “What you are doing today is absolutely ahead of the curve in terms of defense department budgeting and strategic planning.”

Cliff Wang, computing science division chief and program director for information assurance for the U.S. Army Research Office, served as co-organizer of the conference. Wang said he hopes cooperative research by government, industry, and academia will provide the breakthrough technologies needed to protect electronic hardware in the future.

“The ARO supports the advanced research taking place at UConn and at other leading institutions around the country,” Wang said. This year’s conference marked the third time UConn and the ARO have jointly sponsored symposiums regarding cybersecurity and hardware assurance.

UConn’s Center for Hardware Assurance, Security, and Engineering (CHASE) came into existence last year, and is supported by a core team of nine interdisciplinary software and hardware specialists from the School of Engineering. The Center is based in UConn’s Information Technology Building.

A national consortium of hardware security specialists – led by Tehranipoor and other experts at UConn – recently received a $1.3 million federal grant to conduct wide-ranging research designed to protect the integrity of integrated circuits. The other institutions involved in the project are the Polytechnic Institute of New York University, Rice University, and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Last year, U.S. Sen. Joseph Lieberman came to UConn to promote the bipartisan Cybersecurity Act of 2012. Lieberman chose UConn for his tour because of the University’s research strengths in this area. UConn was named a National Center for Academic Excellence in Information Assurance Research in 2010, and the University’s National Security Agency Center for Information Assurance and Computer Systems Security or CIACSS is supported by more than $2 million in federal research grants.