[yframe url=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nwJsxLOilcc’]

The young boy, Jack, shyly approaches his friend in a classroom at Whiting Lane Elementary School. This is the last time they’ll see each other, and Jack has a gift for his playmate: a picture of the two of them together, and the words, “I’ll miss you.”

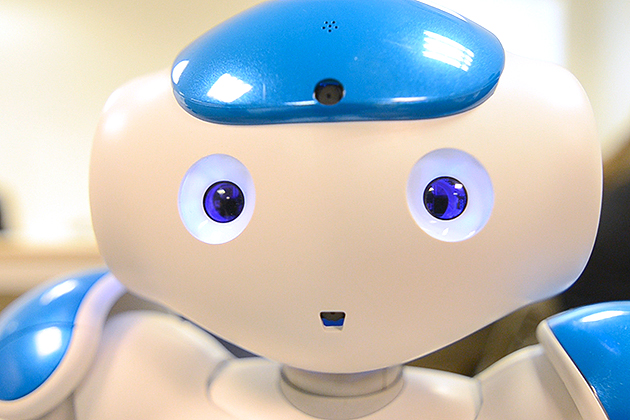

A common enough scene, except the “you” in this case is a humanoid robot programmed by researchers affiliated with the University of Connecticut and Movia Robotics to help children with learning delays like those on the autism spectrum improve their social and communication skills.

“Hi, Jack,” the robot chirps in greeting, before he and the student get into a sequence of activities designed to help Jack not just in the classroom, but in his daily life.

Timothy Gifford – who is the CEO of Movia Robotics as well as the director of the Advanced Interactive Technology Center at UConn’s Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention (CHIP) – sees the work as having potential to cross over into the marketplace.

“That’s really the goal: to take this out of the lab and into the classroom,” he says. “One of the reasons we wanted to make this a commercially available product is to get it into the hands of as many schools and students as possible.”

That’s going to take some time, and the project is still in development, as Gifford and his team learn what works, and what a high-tech product like a robot needs to have in order to function in the world of elementary school kids and daily use.

This is ultimately a very satisfying project to be involved in. It’s something that’s not just interesting from a research perspective, but something that can also make a difference in people’s lives.

At his lab at the Connecticut Science Center, where he’s currently scientist-in-residence, Gifford works with programmers who are developing the sequences the two-foot-tall robots, which are made by a French company called Aldebaran Robotics, use in their interactions with students.

While the robot engages the students one-on-one, someone else – right now a researcher, but hopefully soon a teacher or teacher’s aide – guides the interaction from a laptop computer. The six sequences are flexible enough to be effective when working with children with different levels of ability: one child delightedly bangs on a drum along with the robot, while another runs through more complex verbal exercises designed to improve his ability to communicate with peers.

“This system is really neat because the robot becomes the focus for the child. The robot acts as sort of the mediator or the deliverer of the information,” Gifford says.

Far from being a potential replacement for teachers, the robots will ideally become a powerful tool for communicating with students who have trouble understanding verbal cues or body language from adults.

The work is currently being done with students in kindergarten through fifth grade at Whiting Lane, with plans to expand to two other elementary schools soon. An exhibit on the project is also on display at the Connecticut Science Center, where one of the robots explains its functions with the aid of a video and a push-button console.

Among the challenges Gifford is working to address are the wear-and-tear the robots absorb over the course of sessions with the students, and what Gifford calls “the novelty factor.”

“We were worried the kids would get bored with the robots after a few weeks, but so far we’ve been able to consistently stimulate interest,” thanks in part to the use of simpler toy robots in conjunction with the state-of-the-art Aldebaran models, Gifford says.

And while more work remains to be done before their research can reach conclusions, Gifford is encouraged by what he’s learned so far.

“This is ultimately a very satisfying project to be involved in,” he says. “It’s something that’s not just interesting from a research perspective, but something that can also make a difference in people’s lives.”