Jeremy Teitelbaum, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, is a guest contributor to UConn Today. Read his previous posts.

As I approached the end of my fifth year as dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, I found myself needing some perspective on the job, as well as a little inspiration, so I went where all academics aspire to go when they need renewal – Harvard. There I joined about a hundred other deans, vice provosts, and other mid-level administrators from student affairs and enrollment management at the Institute for Management and Leadership in Education.

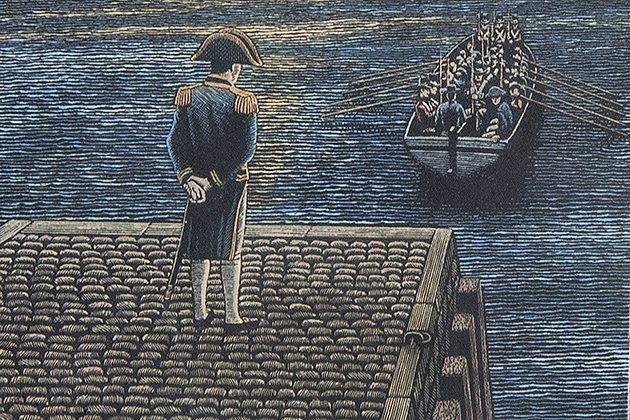

One of the central topics at the institute was “leadership,” a subject we discussed both in theoretical terms and through literature. These were challenging and profound discussions, and they led me to reflect on my own role as a leader. My conclusion: I’d like to be the Horatio Hornblower of academic administrators.

Hornblower is the hero of a series of adventure stories written by C. S. Forester. Over the course of the series, he rises from a lowly midshipman to the rank of admiral in the British navy during the time of the Napoleonic wars. A child of the lower-middle classes, he succeeds without the benefit of patronage through luck, native intelligence, and sheer daring. Gene Roddenberry supposedly had Hornblower in mind when he created the character of James T. Kirk, captain of the starship Enterprise; but Hornblower is a much more interesting, complex, and fully developed character than Kirk.

It’s easy to admire Hornblower as a leader when you look at his accomplishments. He’s a mathematical prodigy, and successfully navigates his frigate Lydia across the Atlantic to Central America, making a perfect landfall after months at sea. He’s a fine planner and strategist, leading a wide range of successful actions on both land and sea. He’s daring and willing to take risks, engaging larger ships and outmaneuvering and defeating them. He shares his crew’s hardships, risking death and disfigurement with them and living as they do on lousy food and little water. He’s also strangely attractive to women, to the point that a (fictional) sister of the Duke of Wellington falls in love with him and, eventually, marries him. Translate all of that to the deanly context, and you get a sense of how I’d like to be perceived.

What’s really attractive to me about Hornblower, though, is what Forester tells us about his inner life. As we learn from the novels, Hornblower is gripped by fear and riven by doubt. He even suffers terribly from seasickness. As he orders his ship to engage superior forces, he thinks of himself killed by a cannon ball, or, even worse, horribly maimed and disfigured. As he carries out a daring maneuver, he imagines a disastrous failure followed by a humiliating court martial leading to ruin.

This is the part of Hornblower I can really sympathize with. Just as I aspire to Hornblower’s accomplishments (in a deanly sort of way), I feel his inner doubts.

The key to Hornblower is that, for all his doubts, he imagines how a heroic sea captain ought to act, and then he acts that way. As a result, he becomes a heroic sea captain. Hornblower tries to do what’s right in the midst of his fears and uncertainty. So, while I think it will be a tough sell to get Horatio Hornblower on the curriculum of the Harvard Institute — he’s probably a little lowbrow for Harvard — he’s exactly the kind of leader that I aspire to be.