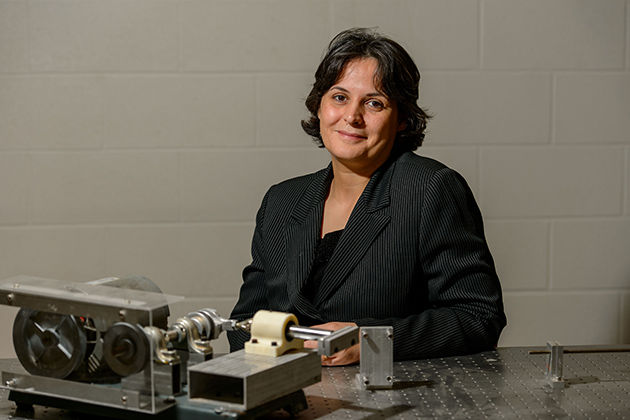

As an expert in additive manufacturing at the University of Alabama, Leila Ladani fabricated new materials and characterized prototype parts for NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville.

Now she is bringing her knowledge and skills in advanced materials science, materials characterization, and the mechanics of materials to UConn as a new faculty member in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. Ladani says one of the things that drew her to Storrs was UConn’s new Pratt & Whitney Additive Manufacturing Innovation Center.

“UConn has two pieces of additive manufacturing equipment [Arcam electron beam melting machines] that are very rare and very expensive, and it soon will be getting additional high-end equipment that will allow us to fabricate different materials in a very unique way,” says Ladani, an associate professor of mechanical engineering in the School of Engineering. “UConn has made a very large investment in this area and that is one of the reasons I came to UConn.”

Ladani arrived at UConn in August 2013. Her Mechanics, Materials, and Manufacturing Lab is staffed with three experienced Ph.D. students who worked with her in Alabama, and she has hired four female UConn undergraduates to work in the lab.

Ladani, who also specializes in the manufacture of nanomaterials and micro- and nanoelectronics, holds two patents and has served in several leadership positions within ASME, a global organization representing more than 130,000 engineers in more than 150 countries. She has conducted research for the Office of Naval Research and the Air Force Research Institute, and her work has drawn funding support from the National Science Foundation, NASA, and private industry.

UConn has two pieces of additive manufacturing equipment that are very rare and very expensive, and it soon will be getting additional high-end equipment that will allow us to fabricate different materials in a very unique way.

One of the areas, she hopes to explore at UConn is the application of additive manufacturing technologies within microelectronics. These ultra-small electronic designs serve as the critical controlling components for many of the devices used in health care and defense applications. Microelectronic devices are currently produced in dozens of small steps, as various electronic parts are added during the manufacturing process. Each additional component and new connection increases the chances of the part failing. Producing a device in a single manufacturing step via 3-D printing and additive manufacturing would be a major advance in the technology.

The challenge, Ladani says, is to preserve the component’s integrity throughout the process and make sure the final product precisely matches the design down to the micron level. But it is exactly those kinds of challenges that she finds most compelling.

“I love working on new ideas,” she says. “Designing, manufacturing, and inventing are all part of being a mechanical engineer. It is the foundation for innovation, conception of new jobs, and economic prosperity.”

A mentor for female engineers

In addition to her research, Ladani will be teaching a course in nanomanufacturing next year. She says she enjoys working with students and would like to see more female students choosing careers in engineering.

While teaching in Alabama, and previously as a faculty member at Utah State University, Ladani started a peer group for female mechanical engineers called WOMEN, an acronym for “WOmen of Mechanical ENgineering.”

It was a group, she says, where women within the academic community could speak freely about the challenges and obstacles they have encountered in what has traditionally been a male-dominated field. She would like to start a similar program at UConn.

“It’s not easy for females, students and faculty alike, because there are so few of us,” Ladani says. “Some people still think women are not built for engineering, and you constantly have to work against that mentality to prove that you are a good scientist.

“In my view, women seem to be doing it better,” she adds, laughing. “But then again, I’m biased.”

Attracting more women into engineering starts at the middle school and high school level where young girls need to know they can be just as successful as boys at math, science, and fields like engineering, Ladani says. That support and commitment to diversity and underrepresented groups extends to the mission of universities.

“We need to do what we can for our students. It’s important,” Ladani says. “I would be happy to work with our female students, serve as their mentor, and let them know that if they have any problems they can come to me. I think that kind of activity and support encourages more female students to get into engineering, and that’s what we want.”

Ladani is, in many ways, a perfect role model. As an undergraduate and graduate engineering student attending the Isfahan University of Technology in Iran and the University of Maryland in the United States, she refused to let cultural traditions and other obstacles deter her from pursuing a future in mechanical engineering. She continued to achieve excellence in her undergraduate and graduate studies, eventually obtaining a master’s degree in heat and fluid mechanics from the Isfahan University of Technology in 2001 and a second master’s degree in solid mechanics from the University of Maryland in 2005. She obtained her Ph.D. in solid mechanics from the University of Maryland in 2007. Ladani has mentored more than 20 undergraduate and graduate students in her role as a teacher, many of whom were female.

“I love what I’m doing now,” Ladani says. “Being a member of the faculty is such a rewarding position. By teaching, I’m using the knowledge I’ve accumulated to advance others, to generate new knowledge, new ideas, and new patents that help my community. All of that is very exciting.”