Completing that final round of chemotherapy and being declared cancer-free is an unquestionable personal health milestone. But it also can mark the start of an uncertain new chapter in a cancer survivor’s life story.

“The leading cause of death in cancer survivors is actually heart disease,” says Dr. Bruce Liang, director of UConn Health’s Pat and Jim Calhoun Cardiology Center. “Patients who have had chemotherapy or radiation are at increased risked for developing heart disease, including heart failure.”

And it’s why UConn Health cardiologists and oncologists are working together on the continuum of care for patients whose cancer treatments involve chemotherapy or radiation.

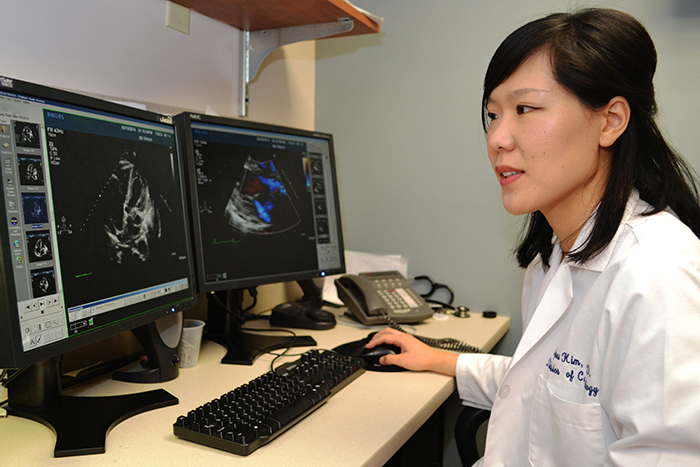

“Many of the chemotherapies used can have adverse effects on the heart, what we call cardiotoxicity,” says Dr. Agnes Kim, a cardiologist who oversees UConn Health’s cardio-oncology program. “The goal of this program is for cardiologists and oncologists to work closely together to identify those patients who are at a high risk for developing cardiotoxicity so that they can be monitored more closely over time and offered cardioprotective treatment, if necessary. We want to protect the heart while beating cancer at the same time.”

It starts with UConn Health oncologists, who determine whether a patient’s risk level for cardiotoxicity to be acceptable, intermediate, or high. Those considered high risk are referred to the cardiologists, who use advanced techniques to watch for early signs of trouble.

“Advanced echocardiography imaging and MRI of the heart are sophisticated technologies which allow us to detect heart dysfunction before it becomes clinically apparent,” Liang says.

Add to that another approach, unique to UConn Health: blood testing to identify certain proteins that may be signs of impending heart damage.

“It’s a highly individualized approach,” Liang says. “It is in the research phase, but this is what we are about. We are doing cutting-edge research, discovering a new way to detect heart dysfunction early on. We hope that one day some of these proteins measured in the blood become biomarkers for early heart dysfunction in patients who receive chemotherapy and radiation. These biomarkers can identify those who will be at risk for developing heart disease from their treatments.”

And that can include patients who are years removed from cancer treatments. Heart disease of this kind doesn’t show itself right away. It can be 10 years or more from the last round of chemotherapy, and by then it can be in an advanced stage. Determining early risk gives cardiologists a chance to prevent its development, or at least slow its progression.

“Involving cardiologists early, from the time of cancer diagnosis, provides us an important opportunity for early detection and, when appropriate, early intervention,” says Dr. Susan Tannenbaum, medical oncologist in the Carole and Ray Neag Comprehensive Cancer Center. “This approach helps turn a potentially serious problem into, in many cases, an avoidable problem.”

If chemotherapy and radiation had an adverse effect on Abbie O’Brien’s heart, it isn’t apparent yet. But her doctors are keeping an eye on it. O’Brien participated in a research trial with measurements before her chemotherapy began, during her therapy, immediately after, and then six months after chemotherapy. She had not only blood tests for biomarker studies, but cardiac MRI and sophisticated 3D echocardiography performed at each time point.

“They studied the effects of chemotherapy on my heart, because I took one of the chemotherapies that is most aggressive against the heart, which is adriamycin – they call it ‘the red’ because it’s blood red and can be very, very toxic to the heart,” says O’Brien, who was diagnosed with breast cancer November 2012. “They do their research to make sure they treat my cancer in the best possible way for me and minimize my risk for developing heart problems.”

Also available to cancer survivors is the Calhoun Cardiology Center’s Lifestyle Modification Clinic.

“Exposure to chemotherapy, radiation treatment and hormonal therapy can increase a cancer survivor’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the future,” Kim says. “In this clinic, cancer survivors will receive extensive counseling and guidance on ways to decrease their cardiac risk by making healthy lifestyle choices in the areas of exercise, nutrition, and weight loss. Cancer treatments can also affect lipid levels and glucose metabolism. This will be monitored and addressed in this clinic.”

Follow UConn Health on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.