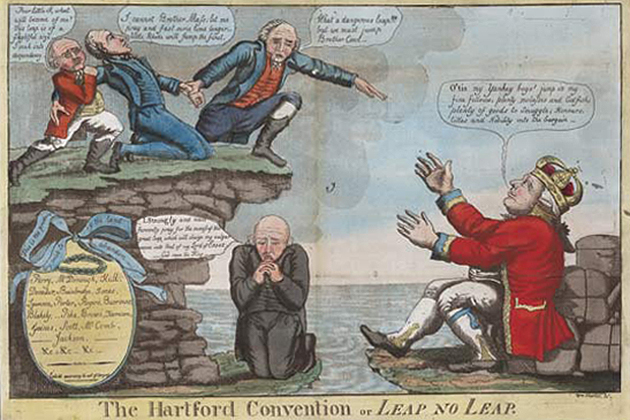

On Dec. 15, 1814, exactly 200 years ago, the Hartford Convention opened for a three-week debate about the relationship between the then-18 states and the Federal government. The meeting had been called by New England members of the Federalist Party. It was held in secret, and there were nationwide fears that the Hartford Convention would call for New England’s secession from the Union.

There were real political concerns that New England was being badly treated by the Union. Since the election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800, the President was a Southerner chosen by an electoral system that gave the slave-holding southern states 60 per cent of a free person for every slave in their allocation of Congressional seats and hence in the number of presidential electors. Indeed, the New Englander John Adams would have been elected to a second term as President in his 1800 race against Thomas Jefferson if slaves, prohibited from voting, were not so counted. James Madison, another President from Virginia, had, with Southern and Western support, led the United States into the War of 1812 against Great Britain. The conflict was hugely unpopular in New England. The feeling in the region was that New England was bearing a disproportionate share of British attacks on coastal cities and merchant shipping.

At the time, things looked to be going from bad to worse for New England Federalists in national politics. Since 1789, five states had joined the Union, four of which – Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, and Louisiana – were in the West or South, both strongholds of the Democratic-Republican Party. More territories – Indiana, Mississippi, Illinois, Alabama among them – were poised to become states, which could leave the New England Federalist Party even more isolated.

Of course, the Hartford Convention did not lead to the secession of New England. It was, however, an important cause of the fall of the Federalists, the party of Washington, Adams, and Hamilton. While the Federalists were meeting in Hartford, American and British diplomats in Belgium were already negotiating an end to the War of 1812, and Gen. Andrew Jackson was battling the British Army outside New Orleans, engineering an American victory that would ultimately help propel Jackson on to the Presidency in 1828. The Federalists were, not without cause, viewed as disloyal to the United States, and soon lost more of their already diminishing public support.

The Hartford Convention is known, as much as it is remembered, as an ideological precursor to Southern secession in 1860-61, and the much more violent battle to divide the Union in the Civil War. Somewhat ironically, New England during the Civil War found itself allied not only with the old Middle States – New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania – but with many of the new North Western States – Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota – once viewed as political threats to New England. And it was the South that felt endangered now by electoral politics. A new Republican majority brought Abraham Lincoln to the U.S. Presidency in 1861 without securing a single Southern electoral vote.

The Hartford Convention and the possible secession of New England from the Union has otherwise more or less faded from view, but its legacy in a way lives on. There is ongoing debate in America over the competing pulls of loyalty between the states on the one hand and the federal government on the other. When Americans are divided on issues like immigration, health care, abortion, the size and role of government, and education, the contest often is framed in terms of “Who should decide”? – the states or the federal government? Almost inevitably, when a minority region feels itself threatened by a contrary national majority, there is a strong temptation for the minority to plead states right.

On Dec. 15, 2014, we remember the Hartford Convention as one of those many instances in our history where we endure the competing pulls of region versus Union in the American political system. Moreover, secession remains a live issue elsewhere from Ukraine to Scotland, from Quebec to Catalonia. As we in the Land of Steady Habits look at debates between regions and a national union both in America and abroad, Dec. 15 is a day to recall that we too debated pulling out of the national union when our regional interests were threatened.