Although her classes were rarely full, and were seldom taught by an actual schoolteacher, Li Wang still showed up to school on time, every day.

It was China in early 1970s, and Wang’s future had already been prescribed: Like the other students, she would graduate high school, then go from her home city of Luoyang to the countryside to learn agriculture from seasoned farmers.

The Chinese universities had been closed for as long as Wang could remember. But still her parents encouraged her to learn as much as possible.

It was extremely lucky, she says, that the Cultural Revolution began to lose its anti-intellectual grip about the time she started high school. Universities were reopening, and the chance of a college degree – and a career – was suddenly in sight.

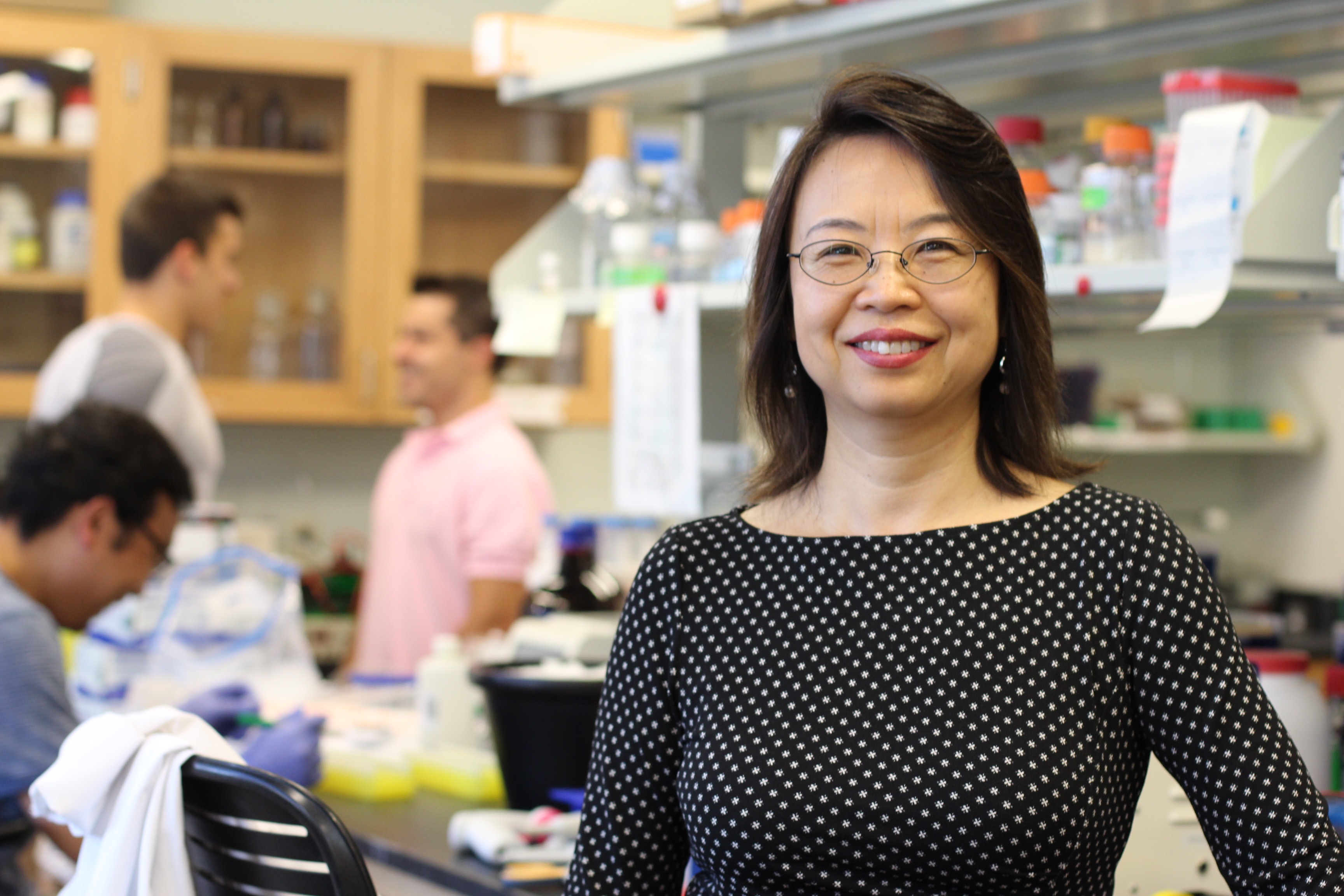

Forty years later, in 2014, Wang arrived at UConn as a professor. With her she brought her research program, currently funded at over $5 million, on the physiology of the liver and its diseases. Her work is a leading worldwide source of new knowledge about the molecular and cellular biology of this vital organ.

A hard-earned education

When Wang applied for universities, her first choice of study was physics, but she was selected for a biology program. But she was satisfied, and says she felt very lucky to get into the biology field, a new area of study at the time.

After graduation, Wang was required to stay on as a lecturer. She had chances to come to the U.S. to study, she says, but the government refused to issue her a passport. She refused to be discouraged.

“There were so many people like me who stayed, even though they had other ambitions,” she remembers. “But that wasn’t my dream. I always wanted an advanced education. So I didn’t give up.”

After six years, Wang was permitted to leave her position, and was accepted to graduate school in neuroendocrinology at the prestigious Sun Yat-Sen University. While at the university, she became the first woman president of the graduate student union – a role for which she won the “Outstanding Student Leader” award from Guangdong province.

In 2000, after a post-doctoral fellowship at Chonnam National University in South Korea, Wang finally procured a visa to move to Baylor College of Medicine in Houston for another post-doc, launching her career in this country. At Baylor, she began her research on a class of cellular proteins, called nuclear receptors, that regulate metabolism, especially those that play a role in metabolic diseases like liver disease, obesity and diabetes.

Ramping up research

One of Wang’s main studies, funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, deals with liver cancer. Wang and her team identified a crucial gene that’s important in liver cancer cell metabolism, and showed that arsenic can affect its expression. Now they’re trying to understand exactly how this regulation works. The results could help to decrease cancer risk in people exposed to high levels of the toxin.

Another project, funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, examines the effect of the body’s biological clock on alcoholic liver disease. Alcoholics often develop fatty liver disease because their body can’t keep up with detoxifying large amounts of alcohol. They also tend to have trouble sleeping, so Wang’s work uses animal models to look at at how disruptions in the sleep and wake cycle affect their liver disease.

Wang has a reputation as an expert at procuring grant funding. She’s earned 27 grants in total, including five current National Institutes of Health grants and the Veterans Administration Merit Award. She also enjoys helping other faculty in the Department of Physiology and Neurobiology with their grant applications. Since national funding for science research continues to see cuts, Wang says she’s worked hard to perfect her grant writing skills.

“It’s very difficult to get funding,” she says. “Many investigators are struggling. So I had to keep learning, to think of new techniques and ideas that would target important fields.”

Along with Professor Jose Manautou of the School of Pharmacy, Wang also hopes to build a center for liver research in the coming years, an initiative she says is important to support research excellence at UConn.

“The department was very fortunate to recruit an internationally recognized scholar of Li Wang’s caliber,” says Larry Renfro, chair of Physiology and Neurobiology.

A passion as professor and mentor

Though she’s been at UConn less than a year and a half, Wang has trained 10 undergraduates to conduct research projects in her laboratory.

Senior molecular and cell biology major Tyler Cappello, who recently won an American Heart Association undergraduate fellowship, is one of the 16 current Wang lab members. Cappello’s experiments have necessitated taking samples from laboratory mice every four hours around the clock, which he says made for some long nights. But he didn’t mind.

“The liver is an awesome organ, and its physiology is really cool,” he says. “It’s the filter that detoxifies your body of all the bad stuff.”

Jason Bennett, a senior student in molecular and cell biology who is working on the arsenic project, says Wang’s mentorship has been exceptional, and has helped him become more confident. When he saw Wang moving into her lab in Torrey Life Sciences in July 2014, he felt the urge to introduce himself.

He began working in Wang’s lab that fall. Like the other students, he often presents at laboratory meetings and has his work critiqued by Wang and her post-docs.

“Now I really like talking to people, and being in the lab has helped with that,” Bennett says.

“Dr. Wang has taught me a lot about leadership,” adds Cappello. “She helps us find our drive, and her way of leading makes us want to do our best.”

Bennett and Cappello both hope to go to medical school, and they say that Wang has prepared them for the rigor of being a doctor. And Bennett says he’ll also take one more important thing with him.

“Dr. Wang has helped me become punctual,” he laughs. “Her level of organization and responsibility has made me be a better student, and a better person.”