In 1769, James Somerset, an enslaved African, stepped off a ship in London with his master, Charles Stewart, a customs officer of the British crown colony of Massachusetts. Two years later, spurred by friendships with free blacks and abolitionists, Somerset fled his master’s house, and an enraged Stewart hunted him down, imprisoned him on the British ship Ann and Mary, and swore to sell him to a Jamaican plantation.

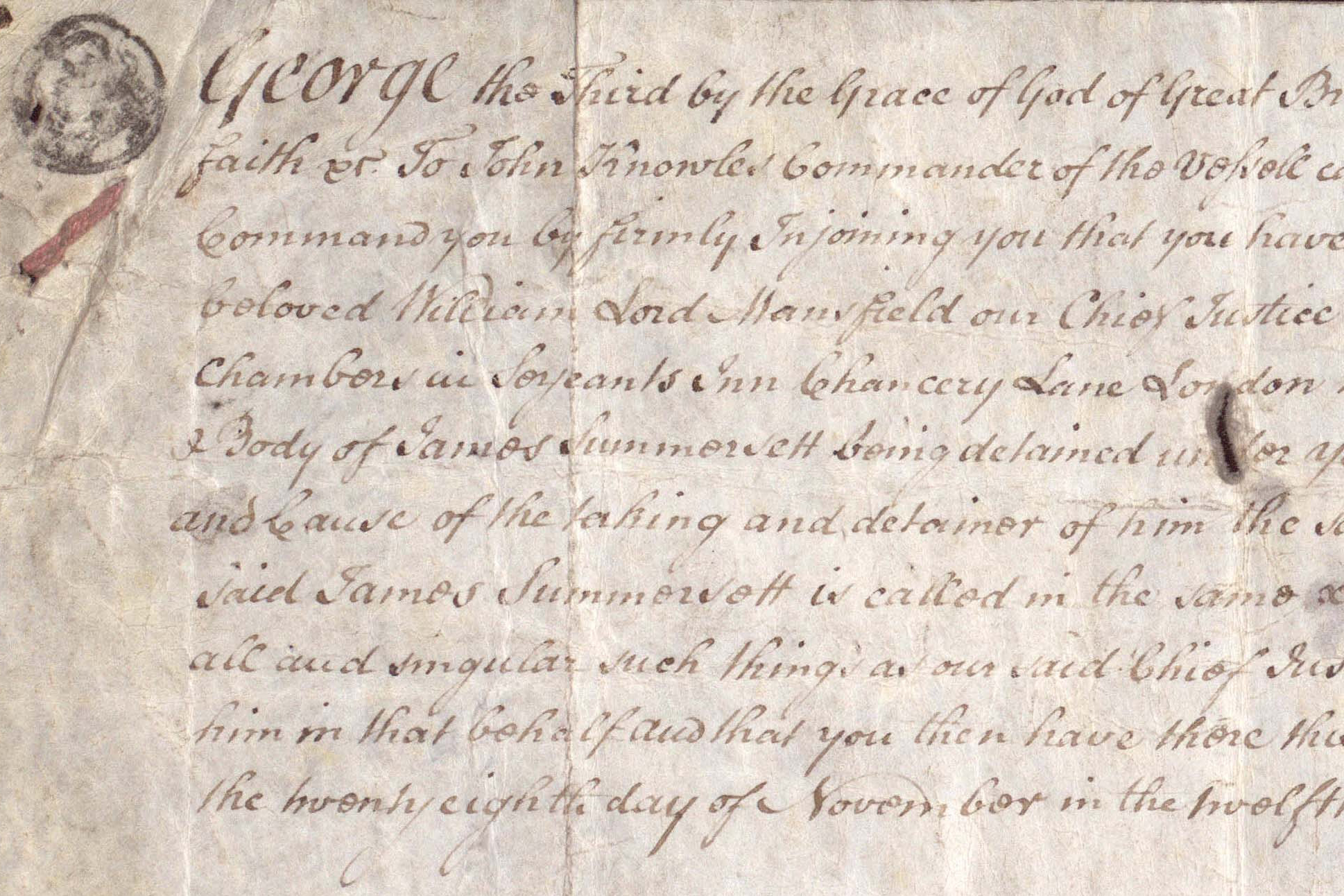

But Somerset’s friends called his detainment unlawful in a country that did not authorize slavery, and demanded a writ of habeas corpus to bring him before the court. Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, granted the writ and, after an extended trial, ruled in 1772 that Somerset could not lawfully be removed from the country. By consequence, he was a free man.

And so the law of habeas corpus – Latin for “you have the body” – was used in one of the first major examples of assigning a human right to a non-citizen, and in so doing, rescuing him from enslavement.

“There’s a recognizable narrative that emerges during this time period involving the rescuing of slaves using the writ,” says Sarah Winter, professor of English in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“It wasn’t just a judicial remedy for unlawful detention, but it also created a legal framework represented in narratives of the time, including literature, that began to give what were understood to be human rights to citizens and non-citizens alike.”

Winter’s research into these stories, both historical and fictional, recently earned her a National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship for 2016-2017.

Her book project, “Habeas Corpus, Human Rights, and the Novel in the 18th and 19th Centuries,” will show how this law evolved from its roots as a method of sovereign power into a judicial process, championed by early abolitionists, for giving rights to those who had none.

A Historical Narrative

The idea that a person could be protected by court summons from unjust imprisonment dates to English common law in the 12th and 13th centuries. Established as a statute in Britain in 1679 by the Habeas Corpus Act, it is a protection considered fundamental to the British constitution and to other common law judicial systems, including that of the United States.

Despite its early use by English kings to control inferior courts, sheriffs, and magistrates, it gained use in the 17th and 18th centuries as a tool to check sovereign power, and ensure that imprisonments were lawful. It is so celebrated, says Winter, that it has become a part of English national identity.

The execution of a writ needs a confluence of specific actors to play out, says Winter. Her work shows that these agents were adopted as recurring characters in novels of the time.

“One of the protagonists is the writ itself, a judicial order written on a strip of parchment, which has the agency to release the enslaved person,” she explains. “Another is the advocate for the enslaved, who goes to the judge to request a writ. There’s the judge, like the famous figure Lord Mansfield, who issues the writ, and the jailer, who perpetuates a cruel imprisonment. And, of course, the prisoner himself.”

Winter will travel to several archives in Britain, notably the British Library in London and the Bury St. Edmunds Record Office in Suffolk, and explore historical news accounts such as that of the Somerset case.

She will also critically examine how novels like Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers and A Tale Of Two Cities, William Godwin’s Caleb Williams, Mary Wollstonecraft’s Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman, and even Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein use this set of characters to comment on issues ranging from the detainment of political prisoners to the imprisonment of wives by their husbands.

The Rights of the Stateless

Although intended to be universal, human rights are sometimes defined as rights granted to persons without citizenship in a government that would otherwise protect them. Because habeas corpus also requires that the “corpus” of the prisoner must appear before a judge, it deals with protecting a person’s physical body from abuse by authorities, and not necessarily with their citizenship. So it holds immense authority, says Winter. It was a tool that, at the time, could suddenly give rights to groups like slaves and women.

“It’s a powerful model, because it is a way of taking an individual body and adjudicating on a certain set of violations having to do with indefinite incarceration and due process of law, regardless of your citizenship status,” Winter says.

Although the United Nations adopted a Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the declaration was not without loopholes. Noted philosopher Hannah Arendt expressed concern that these human rights could not protect the tens of thousands of refugees who had lost citizenship during World War II.

Similarly, in the current refugee crisis, Syrian refugees dispersed across Europe are at high risk of human rights violations, Winter says – especially with an increasing number of countries shutting down their borders.

“People who are displaced by war and violence are in danger of falling into an unprotected status equivalent to statelessness, often because they lack identification papers,” she says. “Refugee camps may also begin to function as places of indefinite custody, if displaced persons seeking asylum are not allowed to cross borders.”

A New Field of Study

That fiction has a long history of reflecting human rights issues is the subject of the emerging field of literature and human rights. UConn has been at the center of the emergence of this new field – which is only about a decade old, says Winter – because of support from its Human Rights Institute (HRI) and Humanities Institute.

Winter held the 2011-2012 Human Rights Institute Faculty Fellowship, and credits the HRI’s interdisciplinary faculty study groups, supported through a University-funded research program on humanitarianism, as a major force in that movement.

Through literary and historical analysis, Winter aims to show that human rights are not just rights for people suffering catastrophes in war-ravaged or impoverished regions. Rather, she hopes it shows that our ability to be responsible citizens goes beyond national borders.

“The history of habeas corpus in relation to this history of human rights suggests that there is a form of law that would bridge rights of citizens and rights of stateless and displaced persons,” she says, “and that would apply to them equally and align them – so we don’t have to keep seeing human rights as the rights of the rightless.”