When someone mentions video games, chances are the word ‘respect’ is not the first thing that comes to mind. But for social psychologists Hart Blanton and Christopher Burrows, respecting the integrity of the medium is an important facet in delivering public health messages through online gaming.

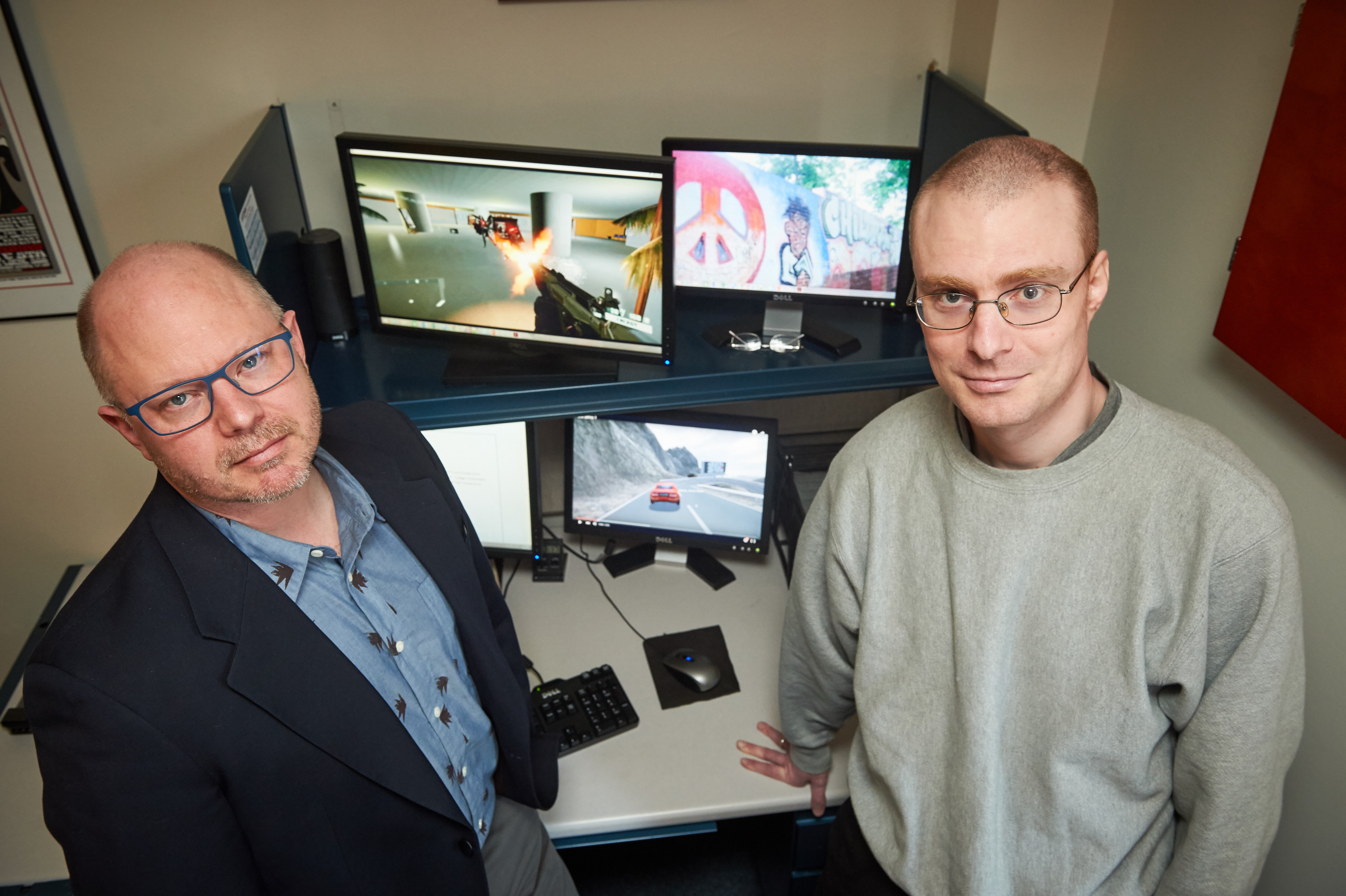

Blanton is a professor of social psychology in the Department of Psychological Sciences and a principal investigator in the Institute for Collaborations on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP). Burrows, a recent UConn Ph.D., is now a postdoc in Blanton’s lab.

Together, they have collaborated on a set of studies appearing online in the journal Communications Research dealing with real-world persuasion from virtual-world campaigns. The paper focuses on what transpires when people who are deeply immersed in video games are exposed to messages about public health issues, such as drunk driving, which are embedded in the backgrounds of gaming scenes.

In a result that may seem surprising, the studies revealed that those individuals most deeply immersed in a game seem to ‘get the message’ more strongly than do the less-engaged players.

“This isn’t subliminal advertising,” says Blanton. “We don’t make any attempt to hide the message we want to deliver. But whatever we include has to be genuine. You wouldn’t be surprised to find an anti-drunk driving poster on the wall of a department of motor vehicles office or even in a library or classroom, but you would be surprised to find something like that in a castle or on a space ship. That’s why we’re careful about where we place these messages.”

Blanton says research shows that in literary fiction, to really enjoy a story a reader has to enter a state of suspended disbelief, such that characters seem real in whatever role they are cast. This is true in television and movies, as well. And to a large extent, it is also true in video games. As long as the presence of a message seems ‘reasonable’ in relation to the story line, the players will be inclined to accept it if they are also psychologically immersed in the game.

The paper reported on three studies where a total of 395 college-age gamers, 60 percent male, 40 percent female, were exposed to anti-driving under the influence (DUI) messages in a first-person shooter game. The anti-DUI posters were placed on the walls in the background of virtual gaming scenes.

In the first study, results showed that the more players reported being transported into the game, the more their own attitudes were affected by the anti-DUI posters. Most could recall seeing the messages with clarity, but memory did not predict the effect. Rather, losing one’s self in the game seemed to cause the background health messages to exert influence on the gamer’s own DUI attitudes.

The use of video games to deliver health messages is an important innovation because, as Blanton describes it, there is a long history in health communications, including in anti-smoking campaigns and safer-sex campaigns, that shows the more you try to influence someone’s behavior, the more you risk moving them in an opposite direction. This is referred to as a ‘boomerang effect.’

Blanton acknowledges that there are very few people who will admit to being ‘pro DUI.’ He says just about everyone agrees it’s a bad idea, but to varying degrees. However, some people engage in the behavior and some people don’t, and those who do are also the ones most at risk of a boomerang. This makes messaging tricky.

Fortunately, their two follow-up studies suggested that their game counteracted this problem. The second study replicated the first, and also showed that when people are heavily immersed in the scenes they are viewing, their ability to argue against the DUI message is reduced. This lowers the risk of a boomerang.

The third study replicated the first two, but it also suggested that the traditional boomerang effect can still occur among a minority of players if they do not become heavily immersed in the game. These individuals resisted persuasion, much as individuals often do in real life.

There are obviously pitfalls in trying to change people’s behaviors but, Blanton says, “We think that by delivering messages when people are in a more susceptible state – when they are transported into the reality of a virtual game where they can be more strongly influenced in a non-coercive way – we have great potential for effective communication.”

Blanton adds that this research predicts an emerging field he refers to as ‘the psychology of virtual reality’ – an area of study that combines the fields of psychology and communication with distinctly 21st-century challenges.