The UConn Reads theme for 2016-17 is “Religion in America,” with Eboo Patel’s Sacred Ground: Pluralism, Prejudice, and the Promise of America as the book.

On July 28, at the Democratic National Convention, Khzir and Ghazala Khan delivered a speech about their middle son, Humayan, who was killed in the line of duty in 2004. As his father eloquently recounted, Capt. Khan was stationed at a guard post in Baqubah, Iraq; spotting a suspicious vehicle, he ordered his subordinates to stay back as he moved to investigate. His suspicions were tragically confirmed: the truck contained 200 pounds of explosives; when it detonated, he along with its two drivers were killed immediately.

Mr. Khan – in recollecting his son’s passing – was quite pointed in his critique of Donald Trump, who just a week earlier had accepted the Republic nomination for president. Immediately following the retelling of his son’s sacrifice, Mr. Khan noted that heroes like his son would never have had the opportunity to serve their country had the presumptive candidate’s policies concerning the wholesale banning of Muslim immigration to the United States already been in place.

The bereaved father then delivered the following admonition: “Donald Trump, you’re asking Americans to trust you with their future. Let me ask you, have you even read the United States Constitution? I will gladly lend you my copy. In this document, look for the words ‘liberty’ and ‘equal protection of the law’ …. Have you ever been to Arlington Cemetery? Go look at the graves of brave patriots who died defending the United States of America. You will see all faiths, genders, and ethnicities.”

While much attention has been paid to the Khan family’s critique of Donald Trump, and much of the discussion has rightly involved the politics of xenophobia alongside the polemics of Islamophobia, it is Khan’s engagement with religious freedom that has the most relevance to this year’s UConn Reads theme – “Religion in America” – and the committee’s selection, Eboo Patel’s Sacred Ground: Pluralism, Prejudice, and the Promise of America.

Khan’s invocation of “liberty” in conjunction with “all faiths, genders, and ethnicities” potently and provocatively attests to both the nation’s past and present.

Although it is widely known that Puritans came to the colonies seeking freedom from religious persecution, and despite the oft-accessed First Amendment clause that stresses “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” what is less apparent is how religious freedom played a key role in the administration of the nation’s first president.

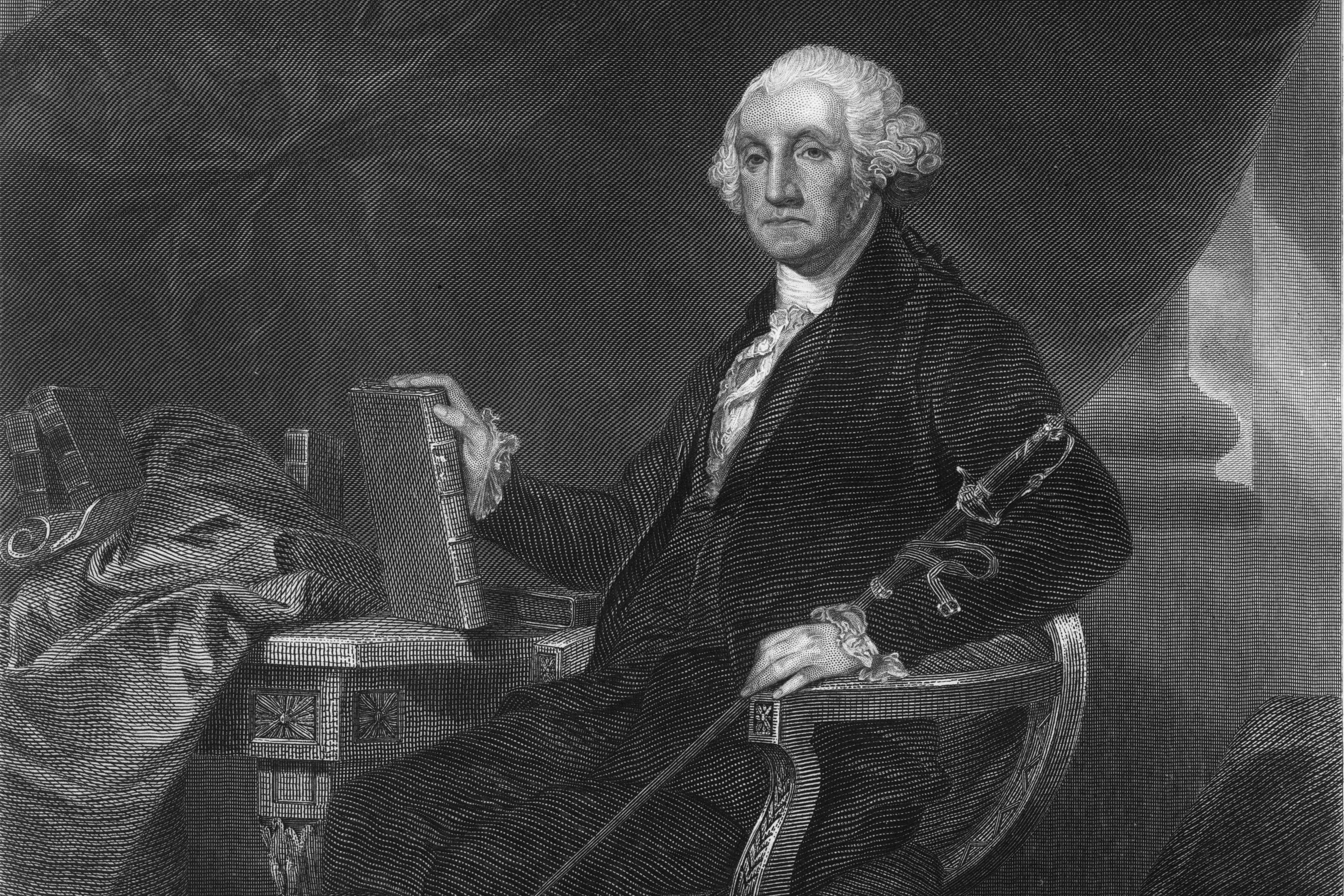

In 1790, President George Washington visited Newport, R.I., and met with representatives from many religious denominations. Among those was Moses Seixas, who led one of the first Jewish congregations in Newport. At issue was the question of religious freedom at the federal level. At the time, requirements for citizenship varied greatly. In Rhode Island, Jewish subjects were protected from discrimination, yet were unable to vote or become naturalized citizens.

Soon after that fateful meeting, the first president composed a “Letter to the Hebrew Congregations of Newport.” In it, Washington stressed, “The citizens of the United States of America … All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship …. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as it were the indulgence of one class of people.”

Washington’s insistence on spiritual freedom as the basis of American selfhood would take legislative form in the passage of the first federal naturalization law that year, which – despite carrying the problematic proviso of “free white persons” – established access to U.S. citizenship regardless of religion or creed. This particular account figures keenly in Patel’s Sacred Ground, which contemplates through religious freedom, interfaith coalition, and pluralistic affiliation the broad-minded promise of the United States.