The U.S. Department of the Interior and Office of the Attorney General this week announced that 17 Native American tribes would be receiving a payout of $492 million to settle claims against the federal government for mismanaging tribal resources. The claims are among the last brought by about 100 American Indian tribes challenging more than a century of federal mismanagement of their property.

UConn Law professor Bethany Berger, who specializes in federal Indian law, has called the government’s willingness to accept responsibility for its actions significant and something that had not been embraced by previous administrations.

Berger developed a passion for federal Indian law after working for a summer in the Tribal Attorney General’s office of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota. The experience, she says, blended her interest in questions of overlapping sovereignty, history, and different cultures, while providing an opportunity to make a difference. After law school, Berger went on to work on the Navajo and Hopi Nations, where she served as director of the Native American Youth Law Project of DNA-People’s Legal Services. She has conducted litigation challenging discrimination against Indian children; drafted and secured the passage of tribal laws affecting children; and helped to create a Navajo ‘alternative to detention’ program. She spoke with UConn Today about the details of the settlement and its implications.

Q. Please explain why this settlement is so significant.

A. In and of itself, it is not so big, but it is part of a series of decisions that, taken as a whole are more important. For hundreds of years, the United States has mismanaged tribal property and the property of individual American Indians. This has been done without consideration of the fact that this actually is someone else’s property. The federal government has managed things in a way that benefits non-American Indian interests or they have neglected the property altogether, holding millions and even billions of dollars in non-interest bearing accounts, a violation of federal law.

Q. Why does the Obama Administration want to settle these longstanding claims?

A. The claims started in the 1990s in a class action lawsuit on behalf of over 100,000 individual Native Americans which then led to many tribes filing claims challenging mismanagement of their resources. The class action case was initiated by Eloise Cobell, a Blackfeet Indian who spent her life seeking accountability for government abuse of Native American resources and working to put American Indians in charge of their financial futures. The Obama administration settled that case in 2010, and has now settled almost 100 tribal claims.

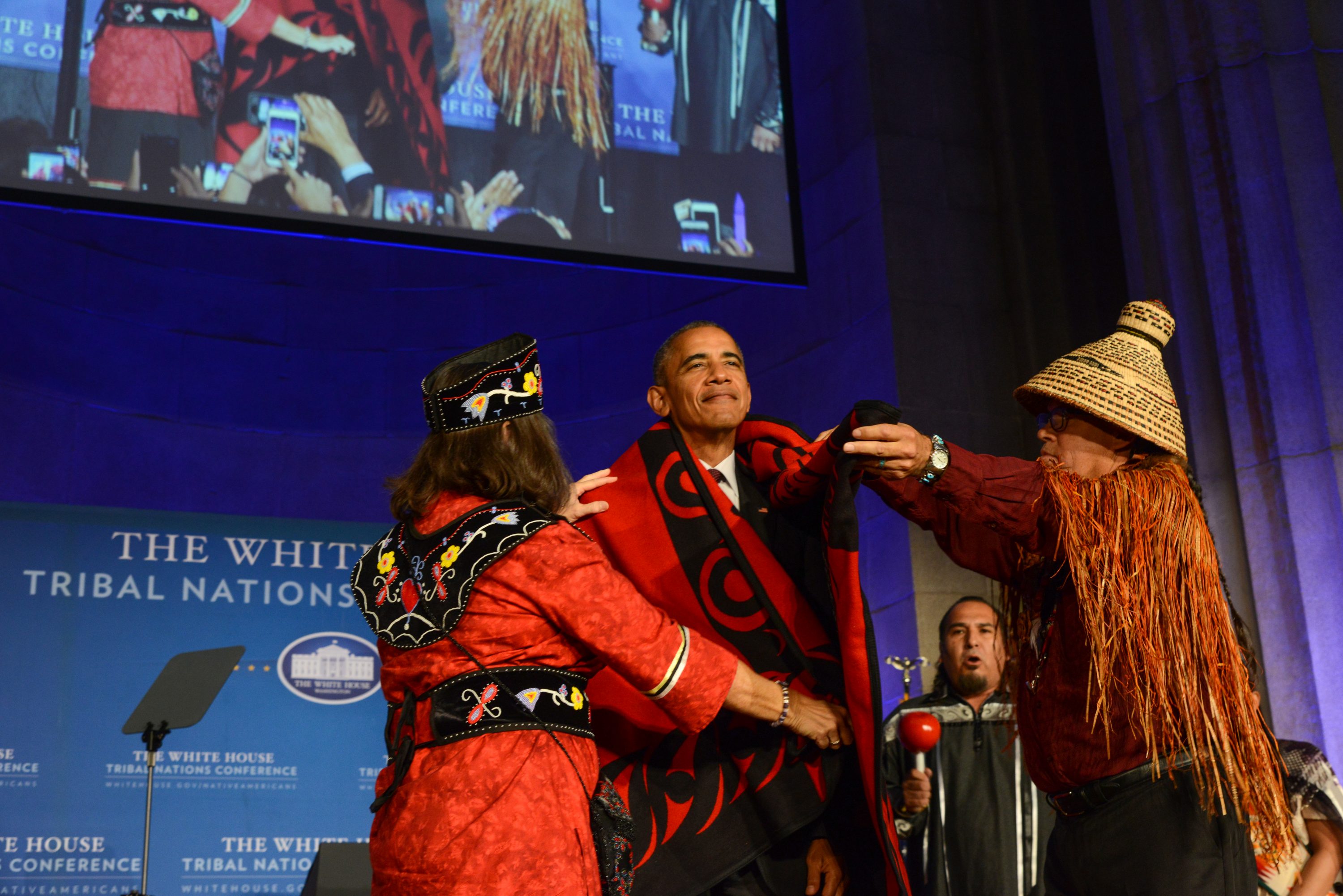

The Obama administration from the beginning really tried to work with Indian Tribes on the problems affecting them, and worked to ensure that when the government does make a decision, tribes have sufficient decision-making capability of their own to respond, something they had not had in the past. Federal authorities now meet annually with tribal nations to ensure cooperation between the federal government and tribes. The United States has tremendous authority on reservations, and too often has exercised it without listening to the communities it affects.

One example of this is in criminal justice, where tribes have limited criminal authority on their own land. With the support of the Obama administration, Congress in 2013 enacted a statute that for the first time gives tribes jurisdiction to prosecute non-Indians who commit domestic violence against Native women on tribal land.

Another example is the United Nations’ Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples, an agreement accepted by 144 nations in 2007. The United States, along with only three other nations, voted against the Declaration. Under Obama, the U.S. finally signed on to the pact in 2010.

Q. What does this settlement mean for the tribes involved?

A. They will have money to build their land base and run their governments – money that was theirs all along and was mismanaged.

Q. Does this begin to close out these kinds of claims from Indian Tribes against the federal government, or are there likely to be more?

A. I’m not sure. My sense is that any additional claims based on historical mismanagement have been settled. The federal government is working to reform trust administration – the process of managing tribal and individual properties. If those efforts aren’t successful, there will be more lawsuits. For decades, Congress and the General Accounting Office have published reports complaining that trust administration was a disaster, but little was done. It may be, though, that this will really trigger meaningful reform. I’m optimistic. I hope that we are in a different age of federal-tribal relations.

Q. Does this suggest to you a change in the way American society generally sees the nation’s past treatment of American Indians?

A. No. American society, if you look back over 100 years, has been saying, “we did terrible things to the Indians and we have to make it better.” What people don’t understand is that tribes are not just a thing of the past, they are modern people with modern governments. I think we have a long way to go before that is better understood and, as a result, there is sometimes a backlash.

An example that continues today is when the children of tribal citizens are removed from their families, as happens with adoption. The response to the Indian Child Welfare Act, which protects against this, is that it’s a racial thing – discrimination against Native American kids and non-Native American families.

What people don’t understand is that it’s not a racial question. It’s a question of tribal citizenship and tribes having jurisdiction when a child is removed. This would not be an issue if it were a foreign country asserting jurisdiction, but that is not part of the discussion at all when we’re talking about these tribal kids.

Another recent example is a suit by a minor from the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians against Dollar General. The suit claims that when the plaintiff, then aged 13, was interning at a Dollar General store on the tribe’s reservation as part of a Youth Opportunity Program, the store manager sexually assaulted him. Store officials argued the tribe should not have jurisdiction over non-member defendants and pushed to have the case heard in a non-Indian court. Both a district and circuit court found the tribe did have jurisdiction over the case, but the store pressed its case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where justices rendered a split 4 to 4 decision. The line-up of amicus briefs made the case look more like an effort to protect big business than to preserve fairness. I think the case shows how far we need to go in recognizing the rights of tribes.