President-elect Donald Trump has already begun backing away from building the “big, beautiful, wall” he pledged to put up between the U.S. and Mexico, but the concept of a monumental divider that became a rallying cry of his campaign continues to intrigue Hassanaly Ladha, assistant professor of philosophy and literature.

For Ladha, a Muslim, the notion of such a wall brought together three ideas at the heart of his academic work at UConn: philosophy, architecture, and political theory. It also hatched a collaboration with Estudio Pi, an architectural design firm in Guadalajara, Mexico, to create a virtual rendition of such a wall that allows the public to imagine Trump’s policy proposal in all of its “gorgeous perversity.”

“I have long had an interest in how states think of themselves,” says Ladha, a self-described architectural activist. “I also have a professional history with designing buildings and I bring that into my work as a philosopher. I have wanted to create virtual architecture for a long time; when I came up with this idea I was so excited by it that I decided to formally create a design lab to pursue the project.”

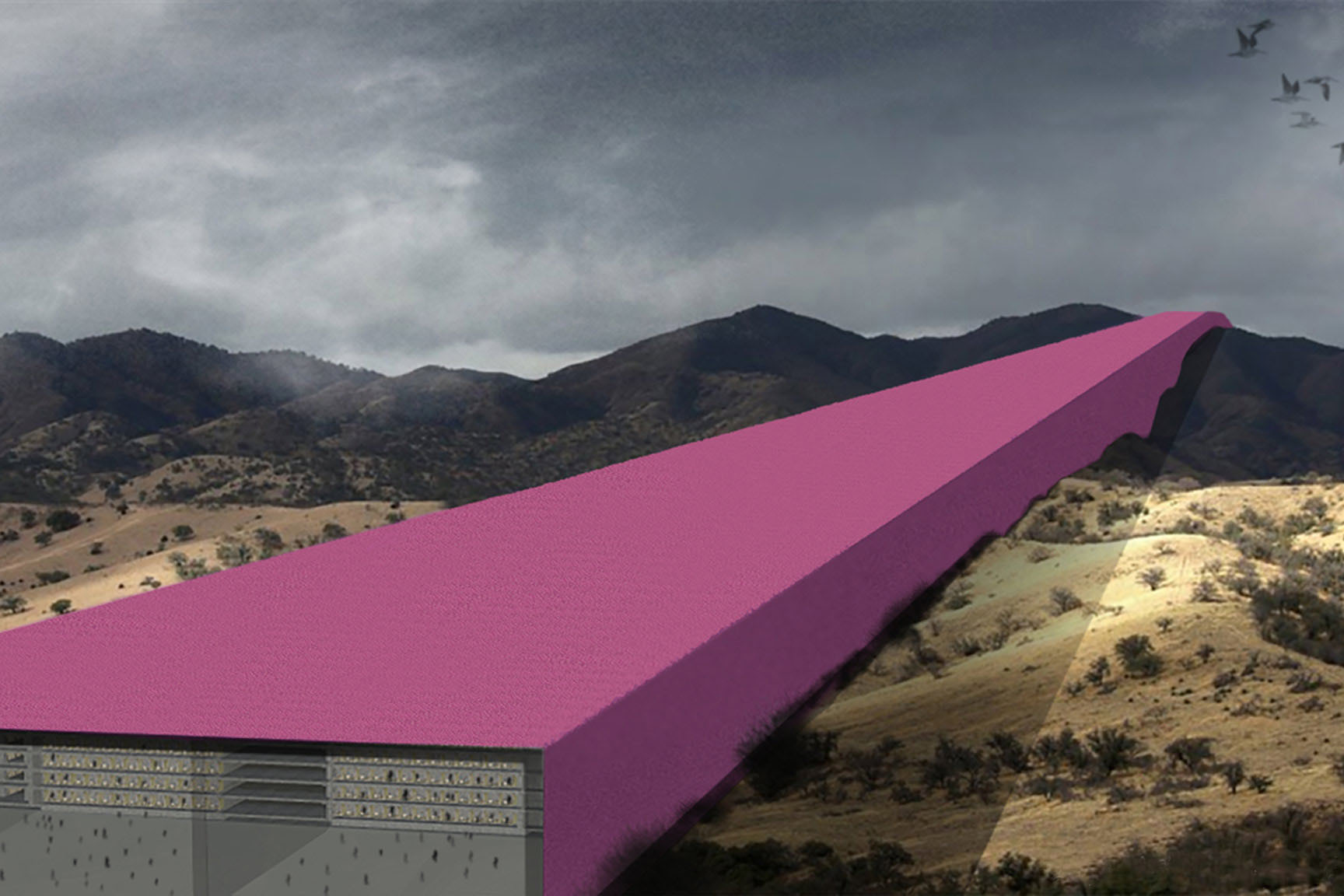

The resulting Prison-Wall began taking shape in September, and was unveiled by Ladha and Estudio Pi creative director Leonardo Diaz-Borioli in the weeks before the election. The “ironically feasible” proposal, conceived by Ladha and given shape through a collaboration between Ladha, Borioli, and his team of designers, calls for a 1,950-mile impenetrable wall along the U.S.-Mexican border “big enough to house, process, and assimilate or remove approximately 11 million undocumented foreign nationals.” Ladha envisioned the mammoth four-story structure as a continuous, self-sufficient city with shopping, health care, residences for 6 million prison staff, and “other facilities to sustain life.”

As presented on Ladha’s Mamertine Group website, the project mimics that of an actual project and, except for subtle tongue-in-cheek references, could conceivably be mistaken for one. Project specifications include detailed descriptions of the site, facilities and operations, legal considerations, and even cost metrics.

To cover the $396 billion cost, for example, the U.S. Department of Justice would employ Mexican labor to operate the prison, reducing labor costs, language acquisition needs for management of the inmate population, and, through the creation of millions of jobs in Mexico, the incentive for illegal immigration from Mexico to the United States. Detainees would provide the labor needed to run factories in this city, and their “income” would be diverted to defray the cost of the structure. The wall would be located on Mexican land and, as with the prison in Guantanamo, be an extra-judicial territory where prisoners would not be protected by the law.

The Prison-Wall project website page also pairs the images with texts, authored by Ladha, on the philosophical implications of border structures, prisons, and other architectural expressions of political will.

“The beauty of the images and texts to me is that they convey the dangerously seductive nature of this rhetoric of exclusion,” Ladha says of the project, “of cultural purity and sovereignty; and also of the state that is founded on and maintains a certain homogeneity.”

Ladha notes that in his thinking about the relationship between walls and the philosophical concept of a state, he sensed that the state bordered by the wall would become something of a prison too. If the purpose of the wall is to exclude what is different, he says, the enclosed state becomes imprisoned by “the banality of sameness.”

Walls are not a new idea, Ladha says, and ultimately, it’s the idea of the state and the notion of cultural purity that he is critiquing. Given the limitless nature of any project of exclusion or purification, The Prison-Wall ultimately articulates the philosophical and logical bankruptcy of building any such structure. Is he concerned at all that the project might be mistaken for a real one?

“I suppose that if you didn’t understand irony, you’d think perhaps we should build a pink wall,” Ladha says. “Hopefully it makes people think, and raises some awareness around what it actually means to have a border wall and expel people. Why do we want to do these things? What is the idea of a state or a country? What kind of people are we embracing?”