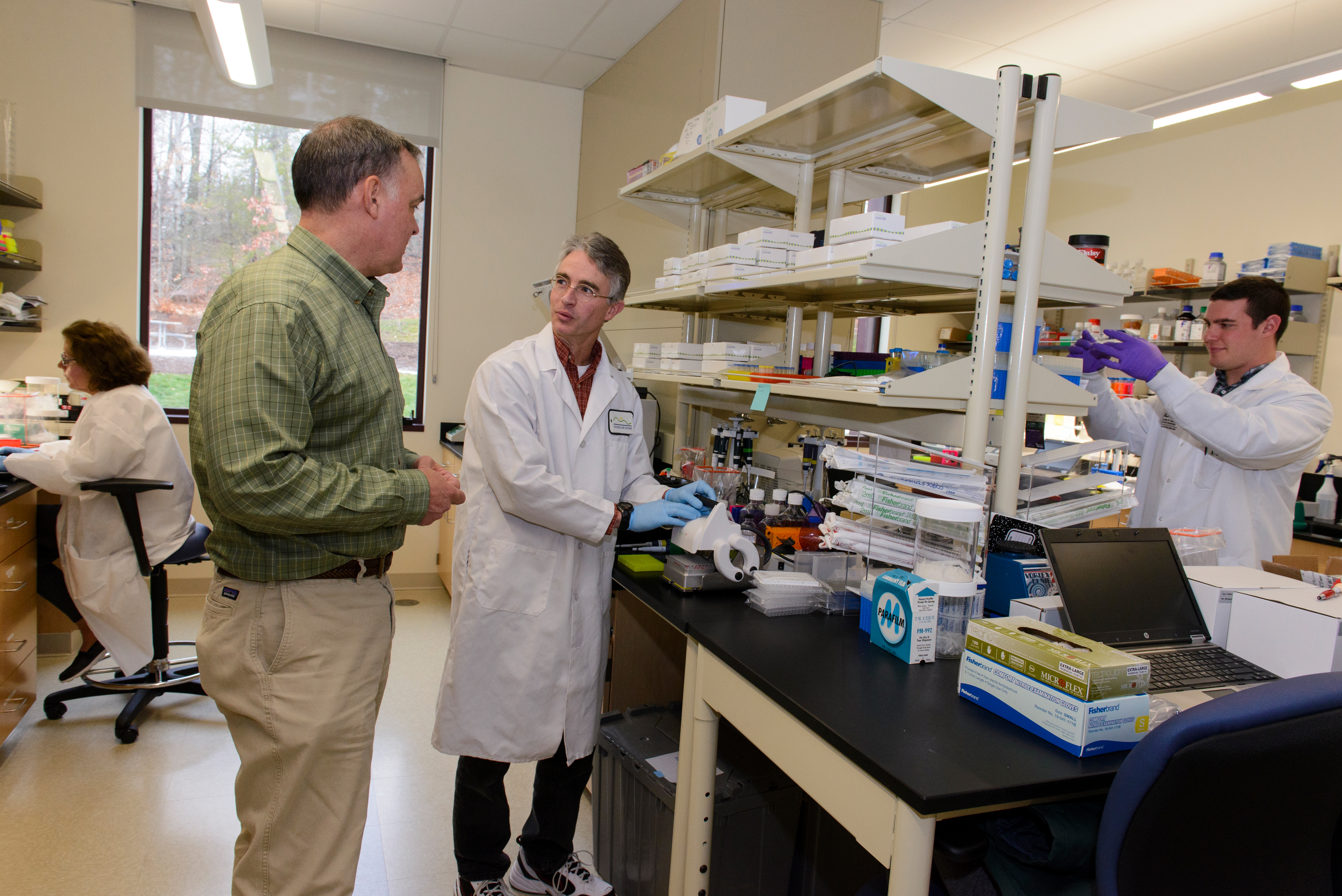

Biochemist Mark Driscoll is trying to crack open a stubborn microbe in his lab at the UConn technology commercialization incubator in Farmington, Conn.

He needs to get past the microorganism’s tough outer shell to grab a sample of its DNA. Once he has the sample, Driscoll can capture the bacterium’s genetic ‘fingerprint,’ an important piece of evidence for doctors treating bacterial infections and scientists studying bacteria in the human microbiome. It’s a critical element in the new lab technology Driscoll and his business partner, Thomas Jarvie, are developing.

But at the moment, his microbe isn’t cooperating. Driscoll tries breaking into it chemically. He boils it. He pokes and pushes against the outer wall. Nothing happens. This drug-resistant pathogen is a particularly bad character that has evolved and strengthened its shell over generations. It isn’t giving up its secrets easily.

Stymied, Driscoll picks up the phone and calls Peter Setlow, a Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor at UConn Health and a noted expert in molecular biology and biophysics. Setlow has been cracking open microbes since 1968.

A few hours later, Driscoll jumps on a shuttle and takes a quarter-mile trip up the road to meet with Setlow in person. He explains his predicament. Setlow nods and says, “Here’s what I would do …”

And it works.

That brief encounter, that collaboration between a talented young scientist and a prominent UConn researcher working in Connecticut’s bioscience corridor, not only results in an important breakthrough for Driscoll’s and Jarvie’s new business – called Shoreline Biome – it leads to a proposal for more research, a new finding, and at least one patent application.

If we were on our own … there would be no place to go to ask questions. But inside this environment at TIP, you can wander around and just ask people. … Even if they can’t give you an answer, chances are they know someone who can. — Mark Driscoll

In a broader sense, it also exemplifies the collaborative relationships that UConn and state officials hope will flourish under the University’s Technology Incubation Program or TIP, which provides laboratory space, business mentoring, scientific support, and other services to budding entrepreneurs in Connecticut’s growing bioscience sector. At incubators in Storrs and Farmington, TIP currently supports 35 companies that specialize in things like health care software, small molecule therapies, vaccine development, diagnostics, bio-agriculture, and water purification.

The program has assisted more than 85 startup companies since it was established in 2003. Those companies have had a significant impact on Connecticut’s economy, raising more than $50 million in grant funding, $80 million in debt and pay equity, and more than $45 million in revenue.

“This is not a coincidence,” Driscoll says as he recounts his microbe-cracking story in a small office across the hall from his lab. “This is what government is supposed to do. It’s supposed to set up an environment where these kinds of things can happen.”

A Bold Idea

Driscoll and Jarvie, a physical chemist and genomics expert, arrived at UConn’s Farmington incubator in June 2015 with a bold business concept but virtually no idea of how to get it off the ground. Both had worked in the labs at 454 Life Sciences in Branford, Conn., one of the state’s early bioscience success stories. 454’s development of a next generation genome sequencing process in 2005 was a huge success, and led to the company being acquired by international healthcare conglomerate Roche two years later. In 2013, Roche announced it was closing 454’s Connecticut offices and moving the operation to its diagnostics division near San Francisco, Calif.

Driscoll and Jarvie decided to stay. They had talked about starting a business based on new technology that, if developed properly, would allow researchers and medical professionals to more quickly and precisely identify different strains of bacteria in the human microbiome, the trillions of good and bad microorganisms living in our bodies that scientists believe play an important role in our health and well-being. The study of the microbiome is a rapidly growing area of biomedical research. There are currently more than 300 clinical trials of microbiome-based treatments in progress, according to the National Institutes of Health, and the global market for microbiome products is estimated to exceed $600 million a year by 2023.

Driscoll says Shoreline Biome is “the most frightening thing” he has ever done: “As scientists, we know that nine out of 10 new companies fail. That sound you constantly hear in the back of your head is the ‘hiss’ of money being burned. The pressure is intense. You have to reach the next level before your money goes to zero, because when the money’s gone, you’re done.”

Driscoll and Jarvie say it was fortuitous that their decision to launch a bioscience company came at a time when Connecticut and UConn were committing resources to strengthen the state’s bioscience research sector.

As part of Gov. Dannel P. Malloy’s Bioscience Connecticut initiative approved in 2011, Connecticut’s legislature allocated $864 million to efforts that would position the state as a leader in bioscience research and innovation. That initiative included the expansion of UConn’s technology incubator site in Farmington, the opening of The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine (JAX Genomic Medicine), and major upgrades at UConn Health to boost its research capacity.

Those resources came at just the right time for a fledgling bioscience company like Shoreline Biome. Driscoll and Jarvie remember the early days when company ‘meetings’ took place at a local Starbucks. The company’s official address and warehouse was Driscoll’s Wallingford garage, now stocked with leftover lab equipment and supplies acquired from Roche during the move. The pair didn’t even have a lab.

But they did have a vision of what Shoreline Biome could be. They knew that George Weinstock, one of the world’s foremost experts in microbial genomics, had just arrived at The Jackson Laboratory’s new Connecticut research site. They reached out to Weinstock, who had been one of their customers at 454 Life Sciences, with an offer to collaborate. He not only agreed, he became their principal scientific advisor.

About the same time, Driscoll and Jarvie began exploring the possibility of renting space at UConn’s TIP in Farmington because of its proximity to people like Weinstock and Setlow.

“If you’re looking to start a bioscience company, in some parts of the state the cost for commercial space is going to be more than your will to live,” says Driscoll. “But here, the rent is graduated. So we were able stay here in the beginning for just a few hundred bucks a month.”

The pair also obtained $150,000 in pre-seed funding from Connecticut Innovations, the state’s quasi-public investment authority supporting innovative, growing companies; and a $500,000 equity investment from the Connecticut Bioscience Innovation Fund or CBIF.

Along with the pre-seed investment funds, Connecticut Innovations’ experienced staff helped guide Driscoll and Jarvie through the early stages of business development and introduced them to the investment community. And, as part of the arrangement, CBIF member Patrick O’Neill sits on Shoreline Biome’s board. O’Neill’s business savvy has been crucial in helping the company achieve its early success, says Driscoll.

Unknown Unknowns

But Shoreline Biome’s good fortune isn’t limited to timely infusions of cash and access to outside investors – although both certainly help. The company also benefits from the internal camaraderie and technical expertise provided through UConn’s TIP.

“If we were on our own in Wallingford or Branford, there would be no place to go to ask questions,” says Driscoll. “But inside this environment at TIP, you can wander around and just ask people. Companies that are ahead in the process are mentoring those just starting. They can help if you have questions about finding a patent attorney, or writing up a workplace hygiene plan, or getting business insurance. Even if they can’t give you an answer, chances are they know someone who can.”

As part of its services, UConn’s TIP holds monthly business meetings at its incubators where CEOs can exchange ideas, ask questions about anything from accounting practices to business law, and hear presentations from different state agencies and research departments at UConn that might help them.

“To channel Donald Rumsfeld, there are things that you know, things that you don’t know, and things that you don’t know you don’t know,” says Jarvie. “This environment is the type of place where you can find out what those unknown unknowns are and start to address them.”

Outside investors also are invited to visit with startups and learn more about them. The fact that CBIF had other scientists and business professionals screen and approve Shoreline Biome’s new technology and business plan prior to making its investment, bolsters the company’s standing with potential investors.

Using the TIP location also allowed Driscoll and Jarvie to save money on purchasing high-end lab equipment. When they need to run a DNA sequencing test on a bacteria sample, they just walk down the hall to a UConn researcher’s lab. Located in UConn’s Cell and Genome Sciences Building, the Farmington TIP shares space with the University’s Stem Cell Institute.

“We need certain types of equipment to process our samples and they have one of those up the hall,” Driscoll says. “They use it maybe once a day and the rest of the time it is sitting there. So we asked if we could use it for like five minutes a day and they said, ‘Sure, just pay us a little bit of money to help keep it maintained and we’ll let you do that.’ They get a little bit of cash in the door and we get access to a machine we couldn’t possibly buy ourselves.”

Tracking the Bad Guys

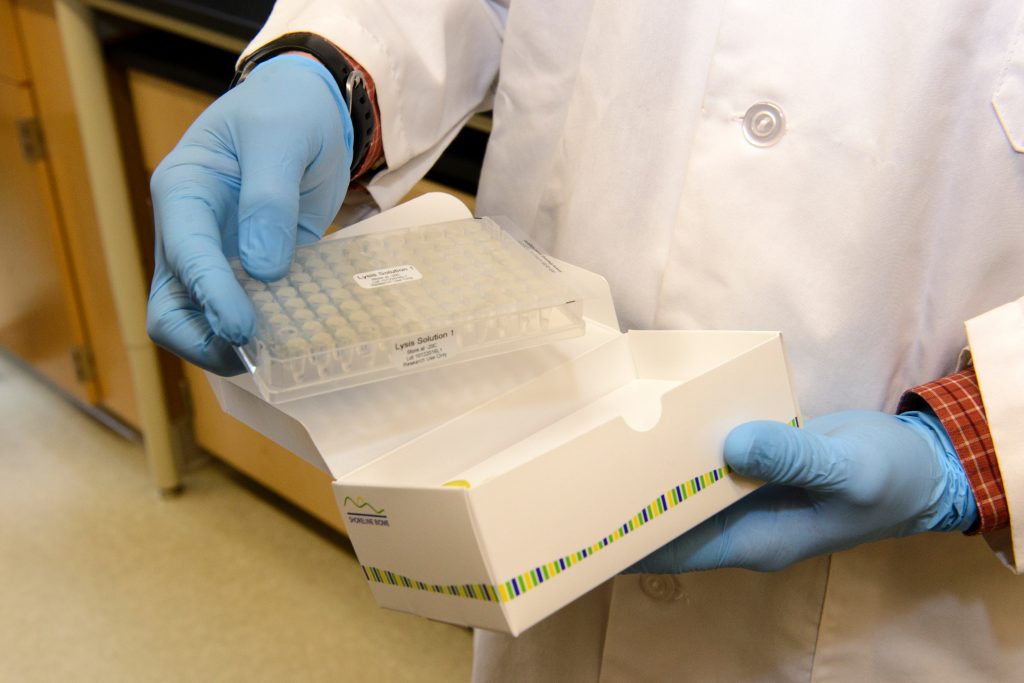

The lab kit Driscoll and Jarvie are currently testing is a low-cost, off-the-shelf tool that replaces hours of painstaking hands-on processing of patient samples for bacteria DNA testing. Rather than processing one sample at a time, the kit can extract dozens of DNA samples at once. It then identifies all of the good and bad bacteria species in those samples within minutes rather than taking hours or days. Its state-of-the-art sequencing technology allows users to see not only all of the different species of bacteria in a sample, but their subspecies as well. It represents a major step forward in the rapidly advancing field of microbiome diagnostics and research.

It’s about getting DNA out of the bacteria from a complicated environmental sample and doing that in a fast, cheap, and comprehensive way, explains Jarvie.

Researchers and medical professionals have previously relied on targeted testing and laboratory cultures to identify different bacteria strains. But many bacteria species are hard to grow in the lab, making identification and confirmation difficult. Even when scientists can confirm the presence of a bacteria such as salmonella in a patient sample, the findings are often limited, which can impact diagnosis and treatment.

“The DNA fingerprint region in a bacteria is about 1,500 bases long,” says Jarvie. “Most of the sequencing technologies out there are only getting a fraction of that, like 150 bases or 10 percent. It’s like relying on a small segment of a fingerprint as opposed to getting the entire fingerprint. You can’t really identify the organisms that well.”

Jarvie describes the difference this way. Say you are running tests for mammals on three different samples. Current sequencing technology would identify the samples as a primate, a canine, and a feline. With Shoreline Biome’s technology, the results are more definitive. They would say, “you have a howler monkey, a timber wolf, and a mountain lion.”

That level of specificity is important to researchers and medical professionals studying or tracking a bacteria strain or disease. Driscoll says the kit is not limited to identifying harmful bacteria like salmonella, listeria, or MRSA. It also can assist researchers investigating the microbiome’s role in maintaining the so-called ‘good’ bacteria that keeps us healthy as well as its role in other ailments such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and even mental health disorders like schizophrenia.

For example, the kit easily lets a researcher compare 50 bacteria samples from individuals with multiple sclerosis and 50 samples from individuals who don’t have the disease to see whether the presence or absence of a particular bacteria in the microbiome plays a role in impacting the body’s nervous system.

“If you don’t make it cost-effective, if you don’t make it practical, people won’t do it,” says Driscoll. “It’s like going to the Moon. Sure, we can go to the Moon. But it takes a lot of time and money to build a rocket and get it ready. With our kit, all that stuff for the Moon shot is already pre-made. We provide the whole system right off the shelf. You don’t need to know how to extract DNA fingerprints, or use a DNA sequencer, or analyze DNA, all you have to do is buy our kit and turn the crank.”

As part of their product testing, Shoreline Biome is working with researchers at UConn Health and JAX to learn more about a particularly toxic and potentially fatal intestinal bacterium, Clostridium difficile, otherwise known as C. diff.

“People who track this disease, especially in hospitals where it is a problem, want to know how it gets in there,” says Driscoll. “Does it come from visitors? Does it come from doctors? You have all these spores floating around. You can answer that by looking at the bacteria’s genetics. But if you can’t get to the bacteria’s DNA, you can’t identify it.

“Our tool cracks open the microbes so you can get at their DNA and fingerprint the bugs to see what you have,” says Driscoll. “It lets people see everything. And we’ve simplified the software so you don’t have to be a skilled microbiologist to do it. A person in the lab can sit down and with just a few clicks, all of this stuff comes up and tells you these are the bad guys, the infectious organisms that are present, and these are the good guys.”

Deer in the Headlights

Initial product testing on Shoreline Biomes’ lab kit has exceeded expectations and the company is continuing to line up investors.

While their focus is certainly on growing Shoreline Biome, Driscoll and Jarvie also have come to appreciate Connecticut’s broader effort in building a strong bioscience research core to help drive the state’s economy. Providing scientist entrepreneurs with an affordable base of operations, working labs, access to high-end lab equipment, and a cadre of science peers ready to help, takes some of the pressure off when launching a new company.

“This is all part of a plan the governor and the legislature have put together to have this stuff here,” Driscoll says. “You can sit around and hope that companies form, or you can try to make your own luck. You set up a situation where you are likely to succeed by bringing in JAX, opening up a UConn TIP incubator across the street, and setting up funding. Is that going to start a company? Who knows? But then you have Tom and I, two scientists kicked loose from a company, and we notice there are all these things happening here. We could have left for California or gone to the Boston-Cambridge research corridor, but instead, we decided to stay in Connecticut.”

Mostafa Analoui, UConn’s executive director of venture development, including TIP, says the fact that two top scientists like Driscoll and Jarvie decided to stay in Connecticut speaks to the state’s highly skilled talent pool and growing innovation ecosystem.

“Instead of going to Boston or New York, they chose to stay in Connecticut, taking advantage of UConn’s TIP and other innovation programs provided by the state to grow their company, create jobs, and benefit society with their cutting-edge advances in microbiome research,” says Analoui.

As the state’s flagship university, UConn provides critical support to ventures at all stages of development, but it is especially important for startups, says Jeff Seemann, vice president for research at UConn and UConn Health.

When asked if they still have those moments of abject fear that they aren’t going to make it, Driscoll and Jarvie laugh.

“Every day is a deer-in-the-headlights moment,” says Driscoll. “Even when things are going well, it’s still a huge risk.”

Adds Jarvie, “It never goes away.”

But during a recent visit to the Shoreline Biome lab, both men are in good spirits. The company met the 12-month goals set in their CBIF funding agreement in just six months. For that effort, Driscoll and Jarvie received another $250,000 check, the second of their two CBIF payments.

In the world of business startups, however, there is little time for extended celebration. The two scientists mark the milestone with smiles and a fist bump, then turn around and get back to work.