Einstein was once questioned how he discovered his groundbreaking Theory of Relativity, his reply was curt as it was poetic, “I thought of that while riding my bicycle.” The first modern bicycle was invented in 1817. Two hundred years later, in 2017, the bicycle continues to ride itself into the halls of history. University of Connecticut’s (UConn) Assistant Professor of Economics Nishith Prakash and Assistant Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics Nathan Fiala, along with Yale University graduate student of economics Kritika Narula, hope to pedal the bicycle as a vehicle for social mobility, educational opportunity and female empowerment.

Riding Waves of Success

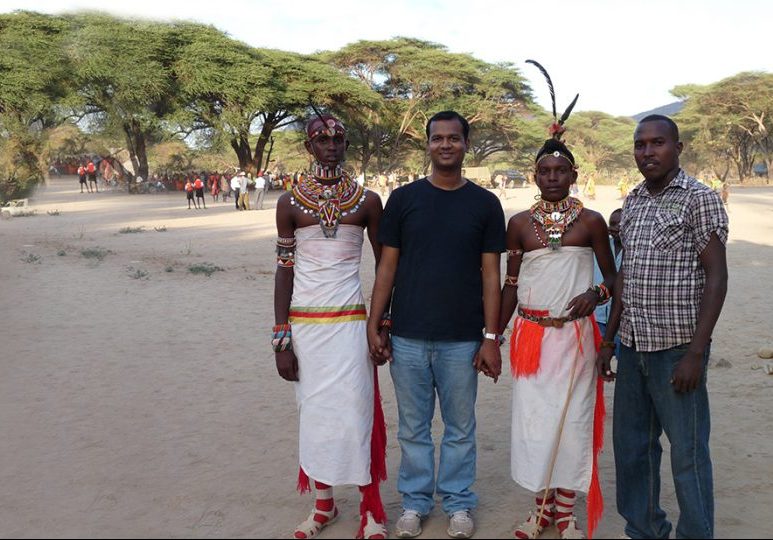

Prakash is one of a few social scientists who intend to gain and provide intellectual leadership in the exploration of development policies with real policy implications. In one of his research themes, he aims to measure, in policy terms, the impact of bicycle distribution and usage in the lives of girls in the Sub-Saharan country of Zambia. The bicycle program is a follow up of an initial research project conducted in India by Prakash and his co-author Karthik Muralidharan, an Associate Professor of Economics at University of California at San Diego, with the aid of the Indian government. In a sort of fortuitous meeting of minds, the Indian government approached Prakash, whom himself is of Indian descent, about empirically measuring the impact their Cycle Program that distributed to girls had on female enrollment. He observed that in India, “large disparities still persist in secondary schooling. As students enter adolescence, this gap continues to widen with a striking drop off occurring around age 14 to 15.” The program was conducted in Bihar, a rural province in India, where “only 11% of the villages in Bihar have a secondary school” and so he argues, “distance is an important barrier to secondary school enrollment and more so for girls.”

Prakash is one of a few social scientists who intend to gain and provide intellectual leadership in the exploration of development policies with real policy implications. In one of his research themes, he aims to measure, in policy terms, the impact of bicycle distribution and usage in the lives of girls in the Sub-Saharan country of Zambia. The bicycle program is a follow up of an initial research project conducted in India by Prakash and his co-author Karthik Muralidharan, an Associate Professor of Economics at University of California at San Diego, with the aid of the Indian government. In a sort of fortuitous meeting of minds, the Indian government approached Prakash, whom himself is of Indian descent, about empirically measuring the impact their Cycle Program that distributed to girls had on female enrollment. He observed that in India, “large disparities still persist in secondary schooling. As students enter adolescence, this gap continues to widen with a striking drop off occurring around age 14 to 15.” The program was conducted in Bihar, a rural province in India, where “only 11% of the villages in Bihar have a secondary school” and so he argues, “distance is an important barrier to secondary school enrollment and more so for girls.”

Riding a bicycle for these girls means riding their way into spaces of educational advancement and professional development. The researchers found evidence to corroborate the significant impact of the bicycle program, which resulted in a whopping 32% increase in enrollment for girls in secondary school. This effectively reduces the gender gap between boys and girls by a substantial 40% margin. The program is most effective when the distance of commute, between home and school, roughly exceeds 3 kilometers. Researchers note the bicycle program was more cost-effective than other projects such as the Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs), which provides direct financial assistance to girls in order to improve enrollment rates; however, there is minimal guarantee that CCTs were used for the intended purpose of girls’ education and evidence seems to indicate these poverty-stricken families diverted funds to meet other pressing financial needs.

Steering Towards Access – A Zambian Turn

Given the overwhelming success, international relief organizations such as World Bicycle Relief (WBR) and the UBS Optimus Foundation, decided, with the help of Prakash and his team, to test the replicability of this program in African countries, particularly in Zambia. No doubt, there are stark differences in social and cultural norms that exist between Zambia and India, but in many respects, both countries align on a fundamental issue concerning female access to education and the gender gap that persists not merely in this comparative occasion, but globally as well. In collaborating with Prakash to ensure the success of the bicycle program, the Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) reveals, “Zambia is characterized by social norms that favor early marriage and limit girls’ access to education” and so, school attendance in rural areas in the country continues to plague the educational system and family households.” The project will be launched later this year and during which, it is estimated that 4,000 bicycles will be distributed to girls attending secondary school. In similar fashion to the bicycle program in India, the overall aim is to make an appreciable reduction in the gender gap in enrollment between Zambian boys and girls.

Pedaling Empowerment

On this point, Prakash, who sits in his office where his towering 8 feet high bookshelf hugs two corners of the room, remarks, “such a program reduces distance cost, increases safety for the girls, as they ride together, and this allows for empowerment.” Prakash hopes to create a storm of his own, one that changes the landscape of female opportunity, aspiration and empowerment, “as researchers, we are looking at what are ways to change social norms.” Norms that suggest that a woman’s place is in the kitchen and a girl’s position is to help in those chores are costly to society as a whole but even more intimately, detrimental to the psyche of women across the globe. Social scientists, of all stripes, call this phenomenon of regressive social norms, the cult of domesticity.

When questioned why empowerment—why this issue—and what motivated him to be an advocate of such a deeply feminist cause, Prakash spoke in very unmuted terms, “If you change [regressive] social norms, that’s power. I want my work to be read outside of economics.” He continues by toting the importance of measuring a potential policy impact, “you answer questions based on the numbers” and so proving a policy impact, on political grounds, “makes a tiny contribution, one that has a positive impact on girls’ education and simultaneously addresses the gender gap in education” both in India and Zambia, but also across the feminine face of the globe. Prakash’s humble suggestion of a tiny impact belies the real possibility of changing the lives of thousands of girls across two continents.

Girls Not Brides

With arms laying patiently on his chair armrest and head tilted slightly backwards, his voice cracks under the weight of pensive reflection, “This project hopes to change the bargaining power at work [for girls] and to delay the age of marriage.” To illustrate child marriage rates, UNICEF (2016) estimates that 6% of girls are married by age 15 that number jumps to 31% merely 3 years later at age 18. In some regions of the country, marriage rates skyrockets to 60%. Zambia ranks 16thhighest in the world with measurable child marriage rates. Prakash hopes that the familiarity of riding together, as girls, ushers into existence a sea of dogged female will power, where girls begin to develop a collective voice and stand together, as girls not brides.

With arms laying patiently on his chair armrest and head tilted slightly backwards, his voice cracks under the weight of pensive reflection, “This project hopes to change the bargaining power at work [for girls] and to delay the age of marriage.” To illustrate child marriage rates, UNICEF (2016) estimates that 6% of girls are married by age 15 that number jumps to 31% merely 3 years later at age 18. In some regions of the country, marriage rates skyrockets to 60%. Zambia ranks 16thhighest in the world with measurable child marriage rates. Prakash hopes that the familiarity of riding together, as girls, ushers into existence a sea of dogged female will power, where girls begin to develop a collective voice and stand together, as girls not brides.

Cycling Support at UConn

Prakash, along with his co-researchers, acquired significant acclaim for this work in a very vital area. He has been interviewed by a journalist from TIME Magazine and his works has been covered in The Atlantic, The Economist and other nationally recognized publications. Prakash joined the UConn family in 2012 as a member of faculty, “I felt welcomed here and this institution, along with my colleagues, provided aid in the way of financial and non-financial support.” He cites, for example, his joint appointment with the Human Rights Institute at UConn as evidence of that support. Prakash intends to pursue his future work at UConn, one that continues to address issues of great societal and personal importance.