Begun in the 1990s as a project to preserve the puppets that Professor Frank Ballard and his students made for UConn Puppet Arts productions, the Institute’s collection has grown to include marionettes, rod puppets, shadow figures, hand puppets, masks, toy theaters and other forms of object performance from a wide array of cultures from around the world. As Connecticut’s State Puppet Museum, the Ballard Institute endeavors to provide the people of Connecticut with a vibrant source of education and entertainment about the past, present and future possibilities of puppetry.

The World of Puppetry

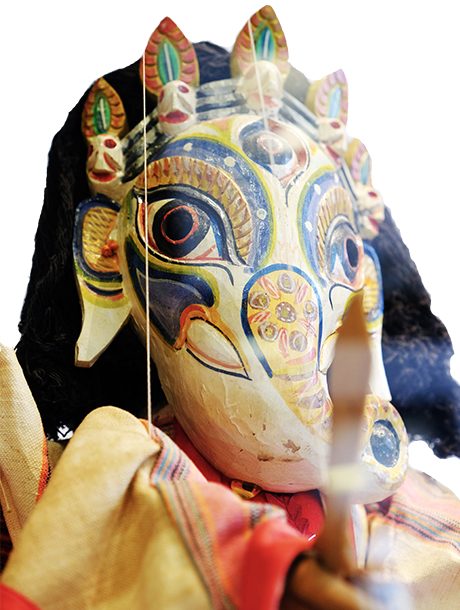

While the Ballard Institute Museum offers a changing roster of exhibitions, drawing on its own collections as well as important historical and contemporary puppets from artists and collectors beyond UConn, a constant presence in the Museum’s lobby is The World of Puppetry, a permanent exhibition of extraordinary puppet practices from around the world. The puppets on display include figures from Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas, and in particular reflect one of the collection’s major strengths: United States puppetry in the 20th century.

While the Ballard Institute Museum offers a changing roster of exhibitions, drawing on its own collections as well as important historical and contemporary puppets from artists and collectors beyond UConn, a constant presence in the Museum’s lobby is The World of Puppetry, a permanent exhibition of extraordinary puppet practices from around the world. The puppets on display include figures from Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas, and in particular reflect one of the collection’s major strengths: United States puppetry in the 20th century.

Part of the education mission of the Ballard Institute is to expand contemporary understandings of puppetry as a television-based form of children’s entertainment. Instead, the Ballard Institute—and The World of Puppetry exhibition in particular—is focused on showing how puppets have been consistent communicators of the most important aspects of societies across the globe, including religion, cultural identity, politics and folklore. In addition, even a modest exhibition such as “The World of Puppetry” suggests how particular characters, stories and puppet techniques have traveled from culture to culture over the centuries as a living link between people everywhere.

Unmasking The Value of Puppetry

Puppet and object performance in the Americas is represented here by masks from Mexico and ritual performing objects from Brazil. Mexican mask culture marks a fascinating combination of indigenous Mayan and Aztec traditions and equally strong Spanish Catholic influences, and the examples in The World of Puppetry reveal how Mexican mask iconography often connects specific animal spirits with the soul of a human character or god. The mask and bird from the Kalapalo people of the Xingù River region of central Brazil also reflect such strong connections between humans and nature.

While puppets, masks, and performing objects are ubiquitous elements of First Nations’ culture, and in particular ritual performance, various forms of marionette, rod, and hand puppet theater arrived with even the earliest European arrivals—first and foremost with the conquistador, Hernán Cortés. Marionettes in particular were perhaps the most popular form of United States puppetry in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as can be seen in the many examples of this technique on display. In the early 20th century, such puppeteers as Tony Sarg, Lou Bunin, the Turnabout Theater, Bil Baird and Connecticut’s own Rufus and Margo Rose used string marionettes in a conscious effort to develop puppetry as a modern American art form. Their high aspirations for puppetry were absorbed by Frank Ballard, who saw their work as a kid in Illinois. It gave him the confidence to establish the Puppet Arts Program at UConn when he arrived here in the late 1950s.

Tony Sarg’s work in particular marks a particular form of American puppet modernism. Although he began his puppet work using the time-tested techniques of 19th century English marionette theater, his graphic design and advertising work with Macy’s department store in New York led him to design something entirely new and unprecedented in the world of puppetry: the giant helium-inflated characters for the store’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. This kind of technological innovation in the United States was matched by an equally strong interest in global puppet culture. Puppet pioneer Paul McPharlin was, among other things, fascinated by Chinese shadow theater, and created his own versions of the Asian form with plastic puppets; and his wife Marjorie Batchelder celebrated (and wrote an influential book about) rod puppetry, paying particular attention to Javanese wayang golek. Batchelder’s stunning rod and shadow puppets for her production “Legend of Lightning” mark a particularly American interest in Asian techniques and new technology. While inspired by Javanese rod puppets, the figures also use sheets of colored plastic to create three-dimensional shadow images.

The hand puppets of celebrated “Queer Theatre” inventor Charles Ludlam mark another particularly modern American form of puppetry. Inspired by 1960s Gay Liberation culture, Ludlam created his ground-breaking Ridiculous Theatrical Company in New York City, but also practiced, as the figures in this exhibition show, the very traditional form of trickster-centered hand puppetry of Punch and Judy. In Ludlam’s hands, Punch thumbs his nose at authority not only to tweak the establishment but also to represent a proud gay identity.

The hand puppets of celebrated “Queer Theatre” inventor Charles Ludlam mark another particularly modern American form of puppetry. Inspired by 1960s Gay Liberation culture, Ludlam created his ground-breaking Ridiculous Theatrical Company in New York City, but also practiced, as the figures in this exhibition show, the very traditional form of trickster-centered hand puppetry of Punch and Judy. In Ludlam’s hands, Punch thumbs his nose at authority not only to tweak the establishment but also to represent a proud gay identity.

Technology offered further opportunities for American puppetry with the advent of television. While many puppeteers experimented with the form in its early years, Jim Henson revolutionized television puppetry in the late 1950s, realizing that the television itself was the puppet stage, and that the malleable cloth and foam rubber faces of his Muppets were perfect for the intimate close-ups of the TV camera.

Finally, Janie Geiser’s puppets for her 2001 production Josiah Meigs and Me are a dynamic representation of New York City’s thriving downtown puppet performance world, which also produced such artists as Julie Taymor and Paul Zaloom. Geiser’s exquisitely wrought characters represent 21st-century experiments in American puppetry, but also, like Batchelder and McPharlin, reflect the strong continuing interest in global puppet traditions and Asian techniques in particular. Geiser’s puppets are manipulated by two or three puppeteers in full view of the audience, a popular technique directly inspired by centuries-old Japanese bunraku puppetry, which is now one of the most popular techniques in contemporary U.S. puppetry. In such ways puppetry today continues to embody practices grown and developed around the world.