Hard work and preparation are undoubtedly keys to success in most situations, but it never hurts to be at the right place at the right time, either.

In the case of Professor of Toxicology in Pharmaceutical Sciences David Grant, Emeritus Professor of Pathobiology Dennis Hill, and UConn graduate Dustin Yaworsky ’03 (Ph.D.), ‘good timing’ has led to a mutually beneficial partnership that has developed through the years. And, it has led to some significant benefits for UConn, as well.

To appreciate how this has transpired requires some history.

Hill was hired by the Department of Pathobiology in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (now CAHNR) in 1976, right after he had finished his Ph.D. at Texas A&M. His primary role at UConn was to run the lab that tested the urine of the greyhounds then racing at the State’s two dog tracks – in Plainfield and Bridgeport – for signs of doping. One of the ways he did this was by utilizing mass spectrometers.

David Grant grew up on a farm in Idaho, and he earned his Ph.D. in environmental toxicology and entomology from Michigan State University. His major interest when studying in East Lansing was insecticide resistance in mosquitos.

Grant took his newly minted Ph.D. to a post doc in molecular biology at the University of California at Davis, followed by a tenure track position at the University of Arkansas. When he spotted a position in the School of Pharmacy at UConn, and given his upbringing in a climate every bit as chilly as Connecticut’s in winter, Grant applied for it.

He arrived here in Storrs in 2001 and began teaching in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences. That’s about the time when he first became interested in the developing field of metabolomics.

Meanwhile, while growing up in Glastonbury, Conn., Dustin Yaworsky had decided he wanted to become a forensic scientist – and this was before CSI became a television staple. As an undergraduate at the University of South Florida, he majored in chemistry. He also worked for chief medical examiner Wayne Duer in the Hillsborough County (Fla.) medical examiner’s office. Duer knew Hill via the Greyhound testing fraternity, and he encouraged his young colleague to pursue graduate work at UConn. That’s how Yaworsky ended up back in Connecticut with Hill as his major advisor.

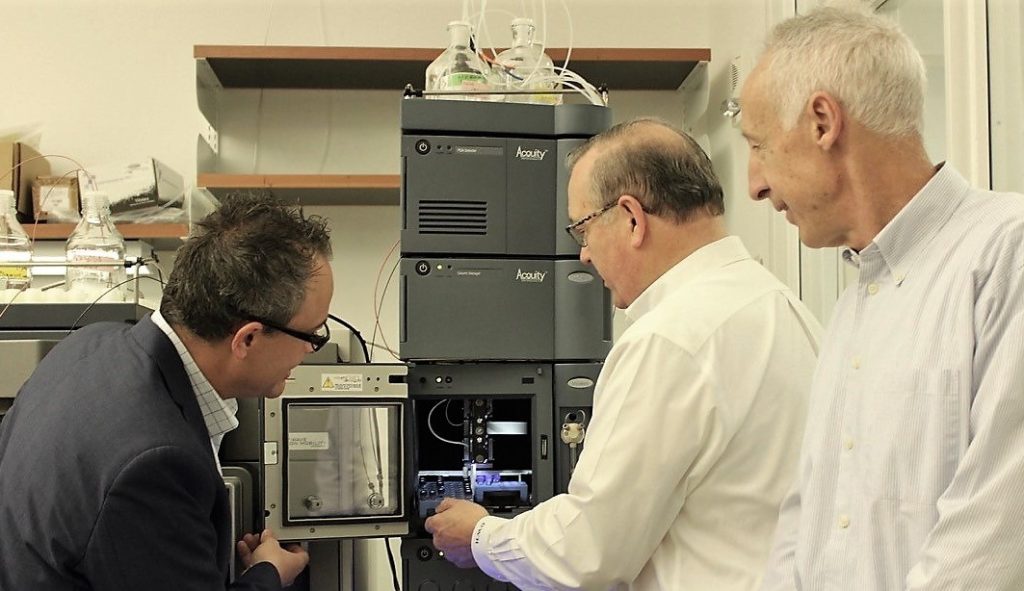

Even though Grant and Yaworsky were at UConn at about the same time in the early 2000s – Grant as a tenure-track professor and Yaworsky as a graduate student – their paths didn’t initially cross. However, they both talk about how Hill was instrumental in guiding their future career paths during that time.

An Emerging Science

“I was becoming increasingly interested in metabolomics – the study of metabolites and the hundreds of thousands of chemicals we make in our bodies – and I discovered that Dennis was the resident expert in using mass spectrometers. It turned out that we had many shared interests and we’ve worked together ever since,” Grant says.

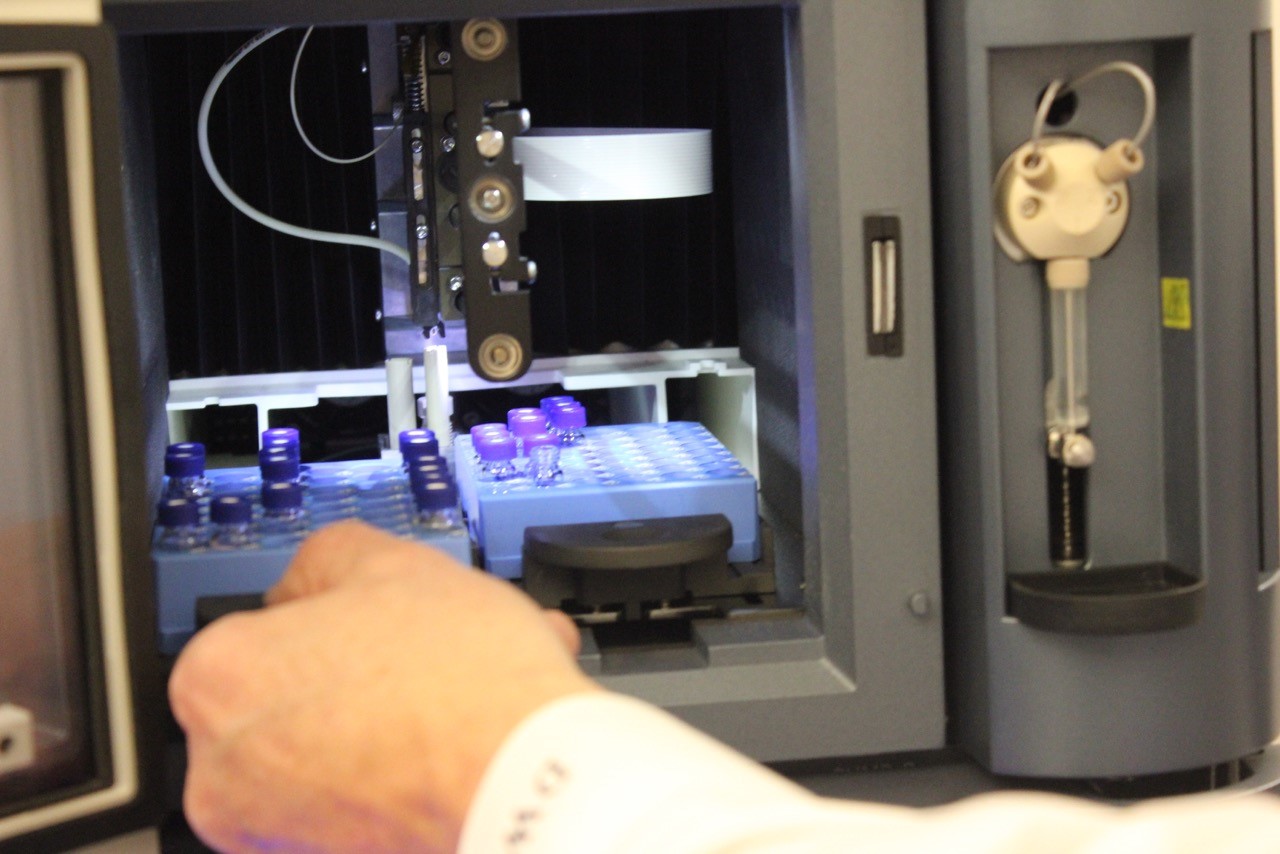

At its most basic definition, mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that identifies compounds based on the atomic sample composition of their molecules and their charge state. This means blind analysis of unknown samples – such as unidentified chemicals sometimes found in the urine of racing greyhounds – is possible since MS doesn’t require detailed prior knowledge of the sample composition.

Grant describes it as sort of like a Google search. “If you are looking for a person named ‘Smith’ in a Google search and you get 5000 hits, that’s like putting a molecular weight in a chemical data base. You may have the same elemental formula but a different structure.

“So you have 5000 Smiths and then you ask yourself how to narrow this down to find the person you are actually looking for. It would be great if you had a first name. An address. An age. Any of those variables you can determine in advance will help narrow down your search. That’s kind of what we do.”

Then, he says, “We can build a model that will allow us to predict the retention time – the amount of time it takes for a compound to pass through a column on a chromatograph – for all those ‘Smiths.’ And if the unknown element we’re testing has a retention time that is similar, then we know we’re close to identifying the compound. The more information we begin to accumulate, the closer we are to having our answer.”

As to why this is important, both Grant and Hill point to things that mass spectrometry can do, such as environmental analysis, isotope dating, tracking trace gas analysis, and the ‘omics’ of proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics – the study of proteins, lipids, and metabolites.

Hill says that the science of metabolomics is increasingly used to diagnose disease, to understand disease mechanisms, and to identify novel drug targets. This is of great interest to the pharmaceutical industry because the science provides a close-up look at gene x environment interactions that can help identify bene biomarkers that can be crucial in the development of drugs.

Grant foresees the day when individuals may be able to go into their physician’s office and after giving a sample of blood, urine, or saliva – or even a tear sample – biomarkers found by mass spectrometry will be used to make definitive diagnoses of a disease before the patient leaves the office. Or, in the case of a traumatic injury, emergency department personnel might take a blood sample, identify a biomarker, and almost immediately know which internal organs have been damaged.

Coming Full Circle

So how does Yaworsky get back in the picture?

He says, “Dennis was an amazing mentor and he was able to help me customize a set of courses that filled all of my areas of interest. These included analytical chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology, and pathobiology. He really prepared me for everything that was to come.”

After earning his Ph.D. in 2003, Yaworsky initially worked in the office of the Connecticut State Medical Examiner, followed by a stint in the toxicology lab at Hartford Hospital. This was followed by a post doc at the University of California-San Francisco where he did mass spectrometry research in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences before beginning a career with a major research and development company focused on laboratory science.

His career path eventually took him full circle, back to New England and a position with the Waters Corporation, headquartered in Milford, Mass. Waters specializes in analytical laboratory instruments and software, and Yaworsky was an Executive Mass Spectrometry Sales Specialist with UConn as one of his clients.

Thanks to Yaworsky’s ongoing interest in the work being done at UConn, and the Waters Corporation’s support of academic research, the University has benefitted from several donations from the company. This includes a donation of $100,000 that resulted in the naming of the Waters Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, and a second donation of an Academic Grant Match that included nearly $50,000 towards the purchase of a Waters Qtof mass spectrometer system now in the laboratory of Professor March Balunas in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Yaworsky says, “When I was at UCSF it was a top five NIH funded center for mass spectrometry research and I was surrounded by people who were Ivy League graduates and others from leading academic institutions from around the world. And I felt I was at least as well-educated and well-prepared as anyone. Maybe more so.”

He adds, “I am forever grateful to Dennis and to UConn for giving me the kind of education I’ve been able to use in my career. Being able to work with Dennis and Dave throughout my career has been continually rewarding, and it has been really important to me to feel like I’m still part of their team.”