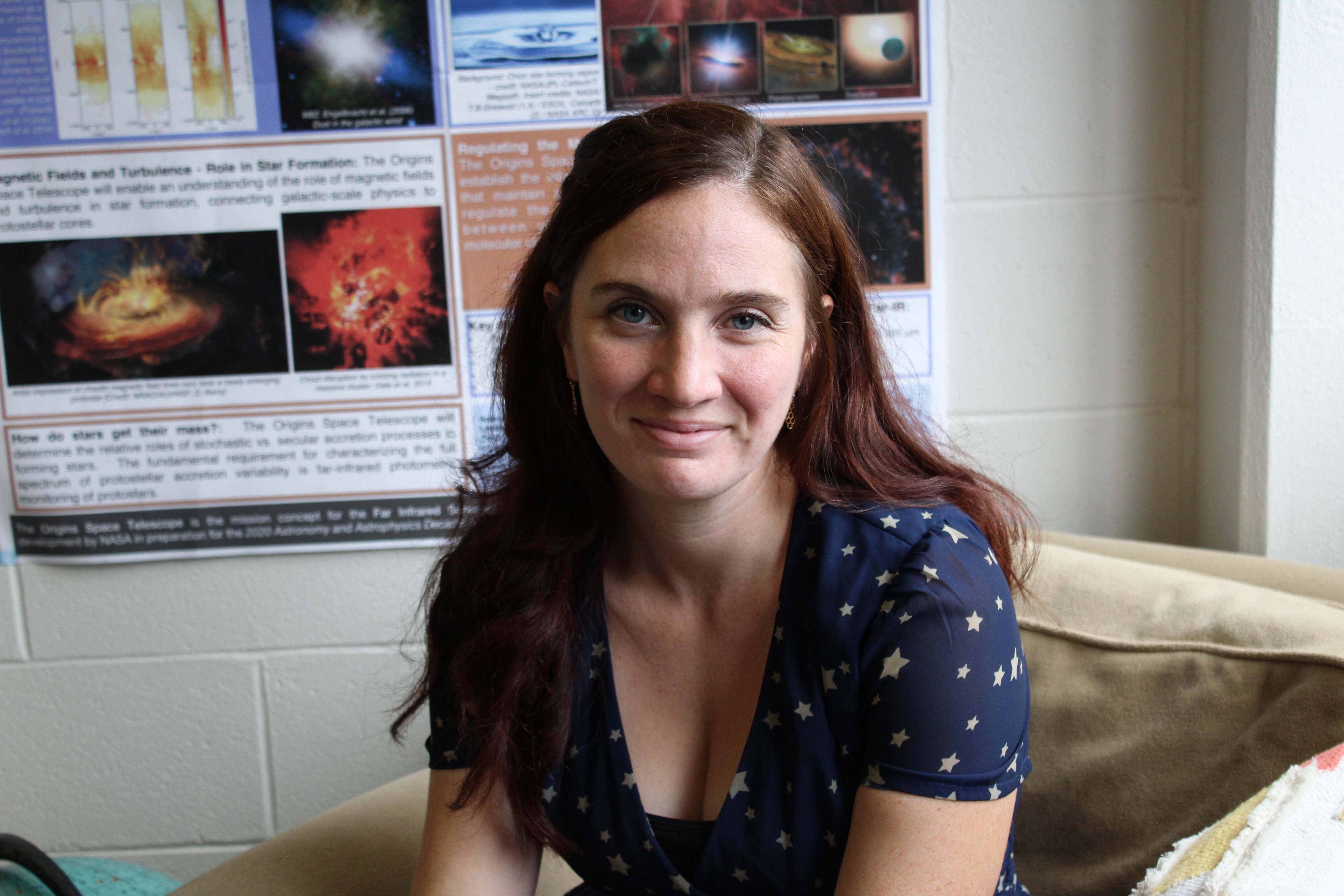

A young Cara Battersby once scrawled out the phrase “Science is curious” in a school project about what she wanted to do when she grew up.

This simple phrase still captures Battersby’s outlook on her research about our universe.

Recently shortlisted for the 2018 Nature Research Inspiring Science Award, Battersby has been working on several projects aimed at unfolding some of the most compelling mysteries of galaxies near and far.

“I’m really interested in how stars are born,” Battersby says. “They’re the source of all life on Earth.”

Many of the “laws” we know about how stars are formed are based exclusively on observations of our own galaxy. Because we don’t have as much information about how stars form in other galaxies with different conditions, these laws likely don’t apply as well as we think they should.

Battersby is leading an international team of over 20 scientists to map the center of the Milky Way Galaxy using the Submillimeter Array in Hawaii, in a large survey called CMZoom. She was recently awarded a National Science Foundation grant to follow-up on this survey and create a 3D computer modeled map of the center of the Milky Way Galaxy.

The center of our galaxy has extreme conditions similar to those in other far-off galaxies that are less easily studied, so the Milky Way is an important laboratory for understanding the physics of star formation in extreme conditions.

By mapping out this region in our own galactic backyard, Battersby will be able to form a better idea of how stars form in more remote areas of the universe.

“I love that astrophysics is one of the fields where I can get my hands into everything,” Battersby says. “Stars are something real that you can actually see and study the physics of.”

Battersby is also investigating the “bones” of the Milky Way. Working with researchers from Harvard University, she is looking at how some unusually long clouds could be clues to constructing a more accurate picture of our galaxy.

“Because of the size of our galaxy, it’s infeasible to send a satellite up there to take a picture,” she says.

Since we are living within the Milky Way it is much harder for us to get a clear idea of what it looks like. We know that the Milky Way is a spiral galaxy, but we don’t yet know how many “arms” the spiral has and if it’s even a well-defined spiral.

These kinds of celestial mysteries have long fascinated Battersby.

Battersby says she would “devour” astronomy books and magazines her parents gave her, but it wasn’t until college that her passion truly developed.

She did her Ph.D. thesis at the University of Colorado on high-mass stars being formed on the disk of our galaxy. During this research she made an astounding discovery that every high-density cloud in space is already in some phase of forming a star, a process that takes millions of years.

This led her to conclude that star formation starts as the cloud is collapsing bit by bit, modifying previous ideas of the timeline of this process.

“If you look at something new in a way no one’s looked at it before, the universe has a great way of surprising us,” Battersby says.

Battersby is a co-founder of the BiteScis outreach program which brings modern science research into K-12 classrooms through partnerships between early-career researchers and practicing K–12 STEM teachers.

She also founded the CU-STARs program to recruit students to STEM disciplines who come from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds.

“It is my belief that equal access to education is the path to a better world,” says Battersby. “I want to widen access to science for all, particularly those who have historically been most unwelcome.”

While astronomy often doesn’t have clear or simple explanations, the process of discovery inspires Battersby to continue her work.

“Sometimes it’s tiring to be your own boss or to feel like the questions you’re asking don’t have a well-defined answer or that the answer is really far off, but when you do make that discovery it’s really rewarding,” she says.

Battersby says it’s important for society to have the kind of curious people her childhood self envisioned scientists as.

“I think that astronomy contributes to society in some of the same ways that art does,” Battersby says. “It may not save your life, but it does make life worth living.”