The internet has been a right in Mexico since the nation’s constitution was amended in 2013 to guarantee universal online access.

Yet just 47 percent of households there reported having internet in 2016, the most recent data available.

To get more citizens online, the government of President Enrique Peña Nieto has invested nearly $1 billion in its “Mexico Conectado” initiative since 2013, adding broadband connections to libraries, schools, hospitals, and other public facilities nationwide, particularly in poor and rural areas.

Ensuring that all Mexicans have access to the internet would do more than just making good on the Constitution’s unfulfilled promise – it would also give the country’s economy a boost, my research shows.

Internet access helps people escape poverty

Forty-three percent of Mexicans lived in poverty in 2016, according to the most recent data from the Mexican Institute of Statistics and Geography. That’s down just 3 percentage points from 2010.

Poverty rates have changed relatively little in Mexico over the past 20 years, despite ambitious anti-poverty programs offering cash assistance, food, health care, and educational opportunities to the poorest families.

With its digital inclusion strategy, Mexico hopes to nudge social mobility upward. That’s because internet access and poverty reduction are strongly connected, as my study of 92 developing countries, including Mexico, confirms.

The internet is now all but essential to economic mobility in a digital world.

Students study and learn online. Unemployed people need the internet to find and apply for jobs. Factory workers use it to organize for better labor rights. Online training teaches corporate employees new skills, helping them get promoted or change fields. Online resources can help farmers plan for weather changes.

Internet access makes it easier to move up in life for other reasons, too. Social media connects people to others outside their immediate circle, for example, and gives them information about their rights as citizens.

Acknowledging the link between technology and poverty reduction, the United Nations made one of its global development goals for 2030 to “significantly increase access to information and communications technology and strive to provide universal and affordable access to the internet.”

Digital divide between rich and poor

In the United States, about 95 percent of people have access to the internet. Rates are similar in Germany, Sweden, Argentina, and other wealthy countries.

Yet billions of people worldwide – the vast majority of them poor, many of them in India and China – still lack internet access. Last year was the first time that more than half the global population had access to the internet, according to Internet World Statistics.

In Mexico, 63 percent are considered internet users. The roughly 50 million people who remain offline are also generally the country’s poorest residents.

In Baja California Sur, one of Mexico’s richest states, for example, 75 percent of households had internet connections in 2016. But just 13 percent of households in Chiapas, a southern state where three-quarters of the people live in poverty, were connected to the internet. In neighboring Oaxaca state, where poverty is also very high, only 20 percent of households are online.

Mexico’s government understands that the digital divide between rich and poor is a problem for the country’s social and economic development. In 2013, it became the first country in the world to make internet access a constitutional right, with government deemed the provider of access.

Recent court rulings in France and Costa Rica have determined that the government cannot restrict internet access. But Mexico is unique in holding its government responsible for providing that service, as it would water service or public education.

Two independent regulatory bodies, the Federal Economic Competition Commission and the Federal Telecommunications Institute, were created to enforce the 2013 law.

Getting Mexico online

A reform that broke up business magnate Carlos Slim’s communications monopoly in 2013 aided in this effort by reducing prices for data plans on mobile phones and wireless connections at home. This helped more lower- and middle-class Mexicans get online.

But internet penetration is still scarce in the country’s poor rural south.

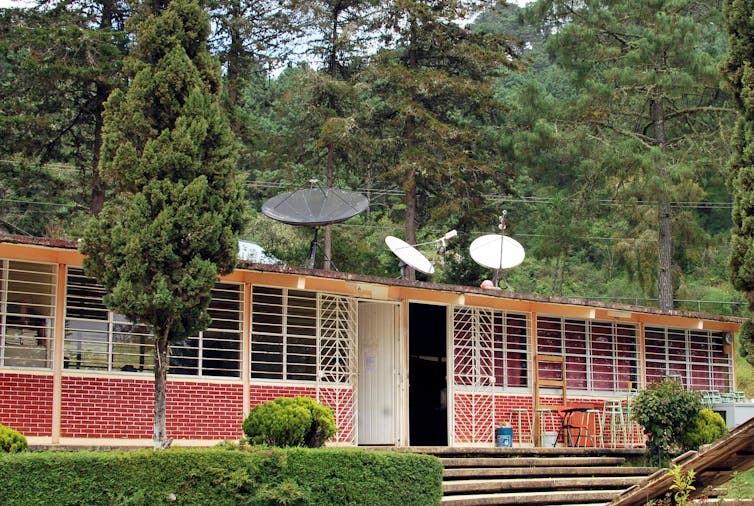

To help those communities, the government has created some 7,200 computing hubs offering free internet access and instructors to help visitors with basic skills like navigating the web, making resumes, and the like.

The focus on computer literacy acknowledges that first-time internet users and older Mexicans may need hands-on help to benefit from the economic opportunities available online.

In heavily indigenous parts of Mexico, the teachers’ challenge is greater.

I interviewed staff and visitors at a public computer learning center in the Oaxacan mountain village of Tlahuitoltepec, where locals speak Mixe. This Mesoamerican language is used by some 100,000 people across the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco, and Veracruz, yet there are few websites in Mixe and it is not among the languages Google translates.

Instructors in such places struggle simply finding enough indigenous-language content online to make surfing the web rewarding and fun.

An estimated 35 percent of Oaxaca residents speak indigenous languages. The proportion is similar in neighboring Chiapas. For many of the Mexicans who live in the areas with lowest internet penetration, then, Spanish is a second language. Others don’t speak it at all.

My findings suggests that language remains a barrier to the country’s digital inclusion strategy.

Getting students online

Mexico also has work to do when it comes to students.

Since 2013, over 5,000 rural public schools have gotten internet connections, and 710,000 tablets were distributed to classrooms as part of the government’s Mexico Conectado program.

Students are also big users of the new government-funded computing hubs.

Even so, only half of all Mexican public elementary schools have internet connections, according to a recent government report.

Getting all citizens online in this sprawling developing country, as Mexico’s government is constitutionally required to do, will be a massive challenge.

But my research indicates that bridging the digital divide will pay off economically in the long run. Giving the poorest Mexicans internet access provides them more opportunity to move out of poverty. And that’s good for the entire country.

Originally published in The Conversation.