UConn Health assistant professor of neuroscience David Martinelli has received a $165,000 grant from the Charles H. Hood Foundation to investigate a potential cause of ADHD.

ADHD (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder) is a condition that makes it hard to concentrate or sit still. ADHD affects 5 to 7 percent of children worldwide.

There is a large need for basic research on the causes of ADHD and I hope to make a critical first step toward a new treatment. — David Martinelli

The current state of ADHD research has many holes, as the causes remain unknown and treatment research is stalled by a lack of adequate animal models.

But one pathway in the brain could provide insight into this disorder. Synaptic protein dysfunction alters how neurons communicate with each other across the synaptic gaps between them and cause diseases known as synaptopathies. ADHD is likely a synaptopathy, but the precise cause of the disorder is not yet known.

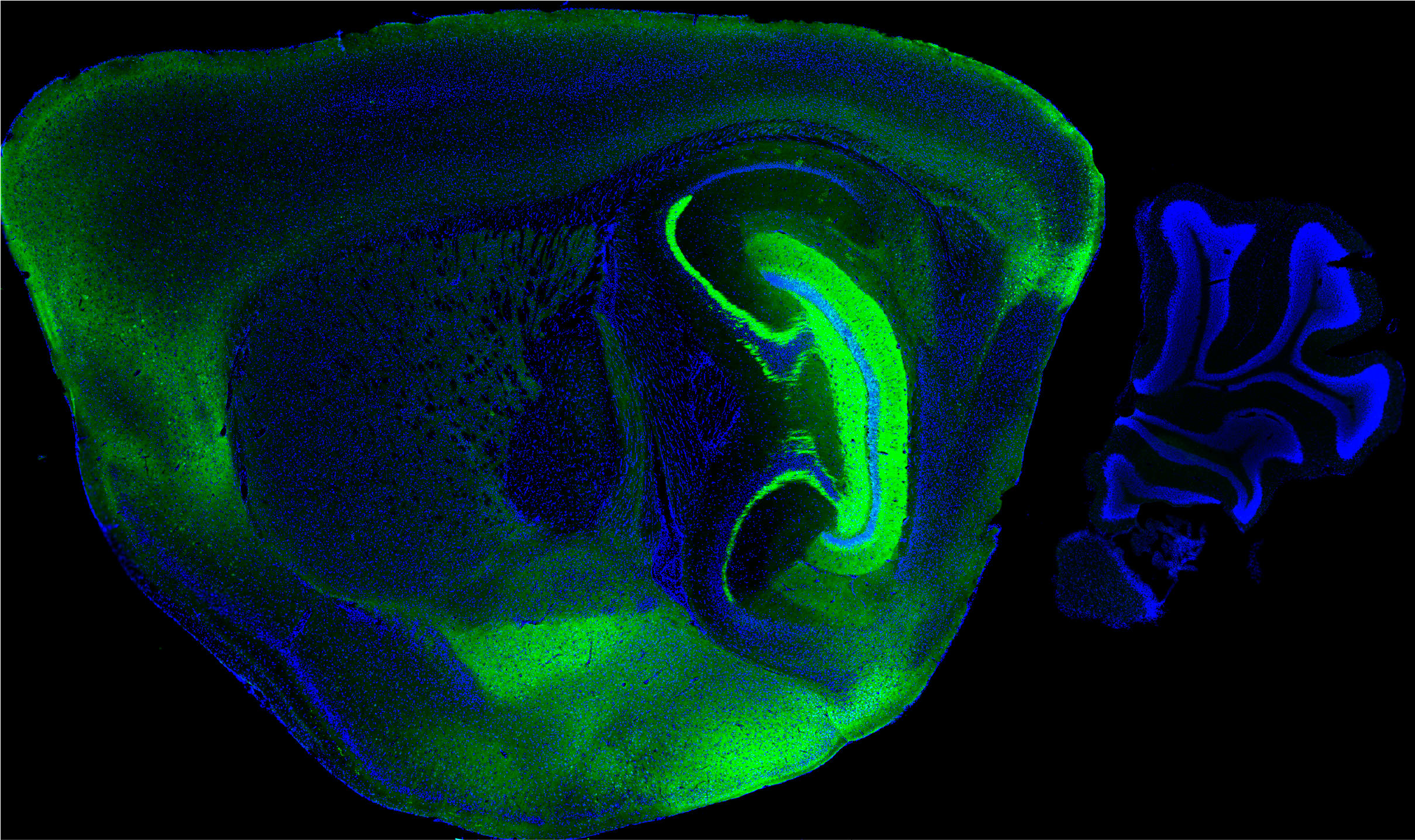

Martinelli recently conducted a genetic analysis on mice in which he knocked out a gene called C1ql3. The result: the mice displayed hyperactivity, sleep disturbances, and a deficit in forming emotional memories, all of which are characteristic of ADHD in humans. This suggests that the gene Martinelli knocked out is somehow involved in causing ADHD.

Through this grant, Martinelli will investigate the hypothesis that the activity of the protein encoded by the C1ql3 gene is mediated by binding to a receptor called BAI3. This means in order for the C1QL3 protein to function properly, it must bind to BAI3 and so, in Martinelli’s experiment, he and his team will create a mutant form of C1QL3 that cannot bind to BAI3. Martinelli thinks this mutant protein will cause the same behavioral deficits he observed in the mice in whom the gene was completely knocked out.

“I am very grateful for this funding from the Hood Foundation,” Martinelli says. “There is a large need for basic research on the causes of ADHD and I hope to make a critical first step toward a new treatment.”

This research will elucidate the cause of the ADHD-like behavioral abnormalities Martinelli observed in the knockout mice. This project will also serve as the basis for future research on ADHD using this pathway which could provide a target for ADHD therapies that treat the neurological root of the problem.

Martinelli received his Ph.D. from the Johns Hopkins University in developmental biology. He completed his postdoctoral training at Stanford University. His research focuses on synapses, synaptic adhesion proteins, and genes related to disorders such as ADHD, schizophrenia, and addiction predisposition.