Jennifer Papa Kanaan, M.D., is a pulmonary/critical care physician who specializes in child and adolescent sleep disorders at the UConn Health Sleep Disorders Center in Farmington, and an assistant professor of medicine at the UConn School of Medicine.

Students in Connecticut receive a powerful education through the hard work of educators, parents and administrators. They are well-versed in the importance of exercise, nutrition and preventive medicine.

But they are often missing a key component to health, emotional well-being and success in both the workplace and in the home. This key to their success is medically of utmost importance, free from side effects and does not cost any money.

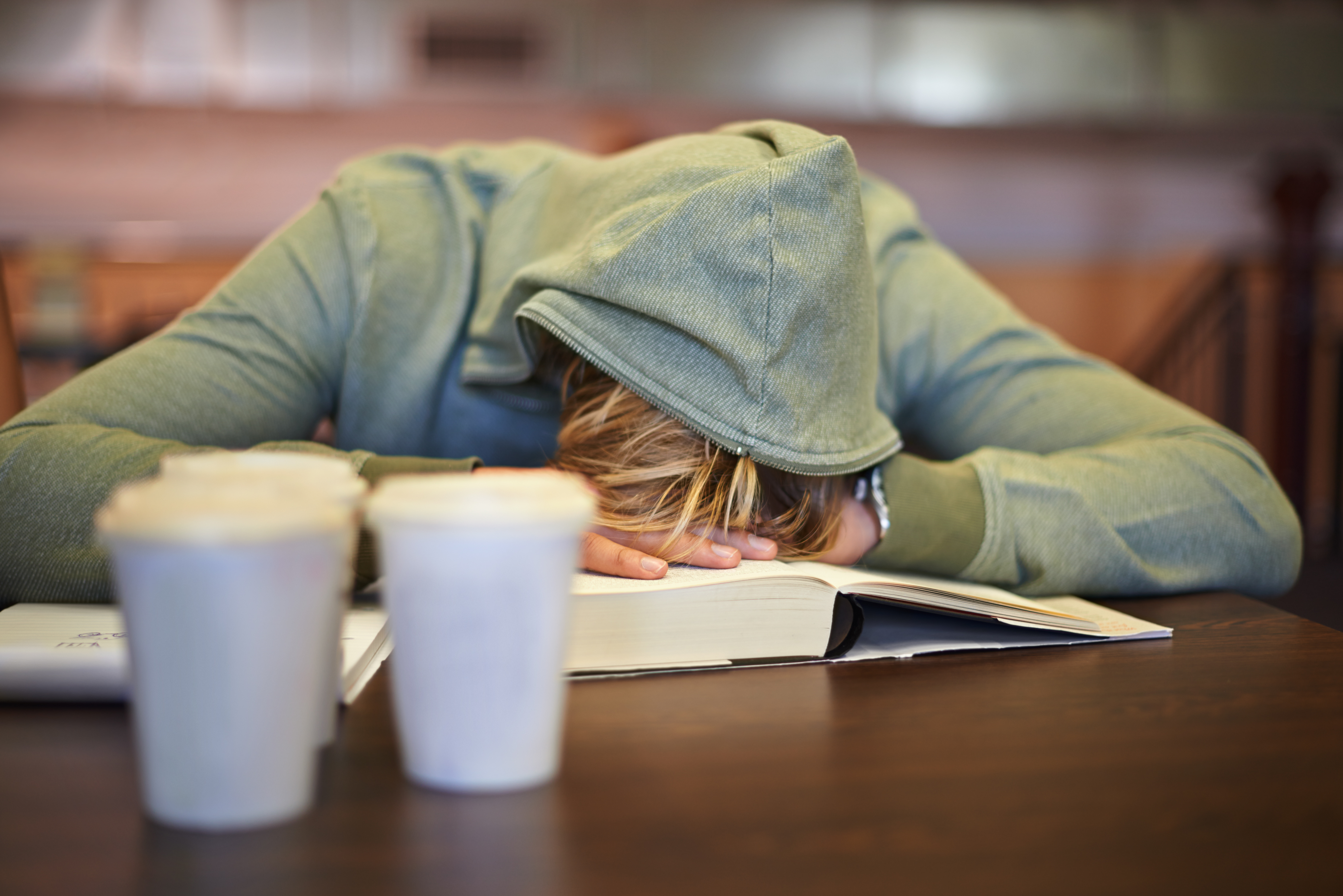

It’s sleep. And its power is astonishing.

As a sleep physician, I have seen patients lose weight, take control of their high blood pressure, improve their response to pain and elevate their emotional well-being. There is no better group to carry the message of the power of sleep than our current students.

Yet we fail them as health educators, parents and doctors. We have such a powerful tool at our disposal, and we fail to use it.

As sleep physicians, we know the science behind the power. There is a curriculum already written by national bodies such as the American Academy of Sleep Physicians. However, for reasons that are unclear to me, we do a poor job teaching our children of the importance of sleep. In a complex time, we overlook easy solutions to good health, and we miss a window of opportunity to teach this formative population about sleep and its crucial role in helping them become their best selves.

Sleep is a cornerstone in the quest for good health, in childhood and adolescence as well as adulthood. The mental and physical health ramifications of sleep deprivation in children, particularly teens, are far-reaching. The science shows a clear connection between sleep deprivation and increased risk of depression, anxiety, suicide, car accidents and behavioral problems, both in school and at home. The American Academy of Pediatrics lists insufficient sleep in adolescents as “an important public health issue that significantly affects the health and safety, as well as the academic success of our nation’s middle and high school students.”

Sleep deprivation is associated with a lack of academic focus. Children who sleep better do better on standardized tests and in the classroom. Most teachers will tell you that students who make sleep a priority are easier to teach. Students consolidate learning and memory during REM sleep.

Curiously, we ask our students to attend school that biologically does not make sense. The American Academy of Pediatrics supports a delayed school start time for middle and high school students. This spring, the town of Rocky Hill decided to push back its school start times. West Hartford schools considered a similar change. These are good steps, and other districts would be wise to look into it. Districts that have changed school start times to be more in line with the adolescent circadian rhythm have been rewarded with better student performance, both in and out of the classroom.

Many districts in other states have adopted this, and the data is no longer controversial. It makes sense to teach students when they are awake. It makes financial sense to employ teachers to teach students who are ready to learn. Yet we ignore the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics and continue to force students to go to school when they are not ready to learn from a sleep perspective.

Numerous studies demonstrate that a delayed school start time is best for students. National organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the CDC support a delayed school start time. What is our primary goal? Isn’t it to educate students? Why do we not fight for our children to have the best learning environment? Isn’t the mental and emotional health of our teens important? In this ever confusing and complex world, don’t they deserve our best effort for a good education?

But it goes beyond test scores. Children who make sleep a priority report better relationships with their parents, friends and teachers. They also make healthier life decisions such as saying no to drugs, alcohol and early sexual encounters. They are safer drivers as well.

“Lights out, time for bed” should be a battle cry of parents, teachers, educators and legislators. Let’s make sleep a bigger part of the health curricula in our schools — particularly leading up to and during adolescence, a most crucial time to influence our children’s habits. Let’s empower the next generation with the scientific knowledge of sleep. Let’s empower them with them with the knowledge to make good choices independent of our parental directives and with the wisdom that sleep brings.

We need to choose the path of sleep education and teach our children that when they deprive themselves of sleep, they’re depriving themselves of their full potential.

Originally published in the Hartford Courant.