When he first entered college, Riqiang Yan wanted to be a doctor. But he soon changed paths when he realized how exciting the research tract was.

“When I had just graduated high school, I was kind of naïve. I didn’t know much about the field until I came to college and became more fascinated by the research,” Yan says. “I wanted to make knowledge in the science part.”

Yan began doing research during his undergraduate thesis project, which was trying to develop a new drug formulation for ulcer treatment at Shanghai Medical University. He was so interested in the project that he continued working on it even after his graduated, which was very unusual at that time for a student who otherwise could have enjoyed time off during the summer break. Yan credits Prof. Yuanming Ma (马远鸣) with providing him that opportunity, and guided him toward the research career path he eventually followed. Following this experience, Yan received his master’s degree in biochemistry at Shanghai Medical University and went on to earn his Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of Kentucky.

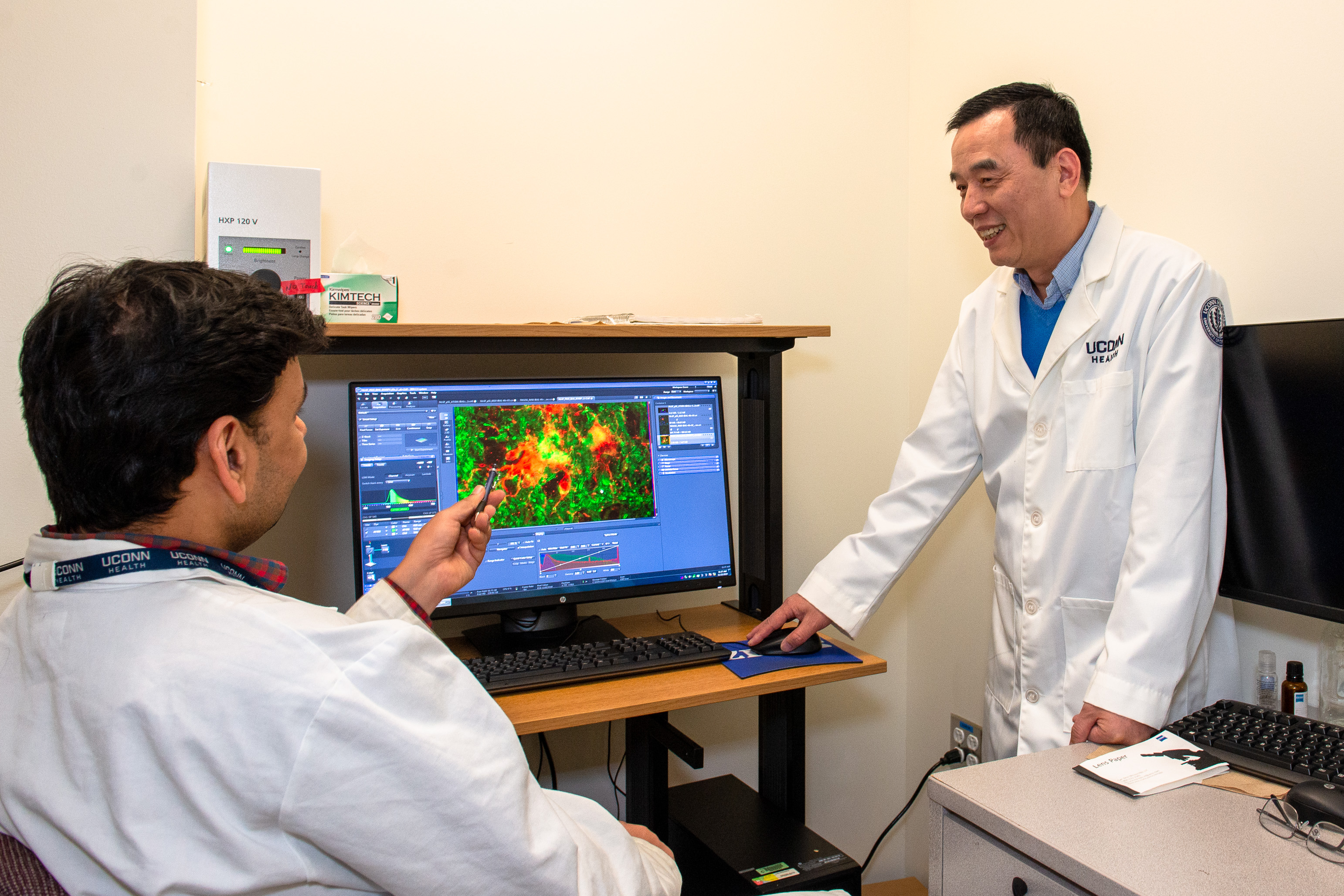

Yan is now one of the world’s leading Alzheimer’s disease researchers. He is a professor and chairman of UConn Health’s Department of Neuroscience, leading discovery efforts at UConn’s School of Medicine. Yan came to UConn from the Cleveland Clinic in 2018. He established the first research program focused on studying Alzheimer’s and other forms of neurodegenerative disease in hopes of potentially discovering effective treatments.

Yan’s arrival at UConn also ushered in a host of research collaboration opportunities across the School of Medicine and its departments of neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry, neurobiology, the Center on Aging, and brain investigators at the University, as well as with the Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine on UConn Health’s campus.

Cutting-Edge Alzheimer’s Research

Now a preeminent scholar in the field, Yan didn’t start out doing Alzheimer’s research. At the beginning of his independent research career, Yan was studying inflammation in lung diseases for global pharmaceutical company Pharmacia & Upjohn. When the company’s priorities changed, Yan shifted over to Alzheimer’s research. The neurodegenerative disease that affects an estimated 5.5 million Americans has no known cure.

“I ended up in Alzheimer’s research by accident,” Yan says. “It was a very exciting time because we had so many unknown questions about Alzheimer’s disease to explore.”

That accident turned out to be extremely productive. One year after making the switch, Yan made a breakthrough discovery.

In 1999, Yan and several other groups of researchers simultaneously discovered that an enzyme known as BACE1 plays a crucial role in the processes that lead to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. BACE1 cleaves amyloid precursor proteins which give rise to beta amyloid. This peptide is the main component of plaques on brain cells, one of the culprits for causing Alzheimer’s disease.

From there, researchers from multiple pharmaceutical and biotech companies began developing trials of BACE1 inhibitors in hopes of stopping the effects of BACE1’s activity. However, all these trials failed. While these failures were frustrating, they taught scientists an important lesson about this key enzyme; not only does BACE1 activity lead to Alzheimer’s disease, it is also responsible for ensuring parts of normal neural activity. By blocking it completely, the treatments did more harm than good.

‘Things Are Not So Simple’

“We still don’t have a drug,” Yan says, 20 years after the original discovery. “These early trials with BACE1 failed because if you simply inhibit it, it interferes with necessary brain functioning. It’s challenging.”

Yan reflects that this is one of the most challenging aspects of his research. The human body is not simple, and neither are the diseases that afflict it. Before we can develop an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, we need to understand how it works at a basic molecular level.

“Many times, you will find out things are not so simple,” Yan says. “We need to understand the biology before we can have an effective drug.”

Most recently, Yan published a paper in the Journal of Experimental Medicine about the role of CX3CL1, a transmembrane protein, on Alzheimer’s disease. Yan found that CX3CL1 is cleaved by BACE1. He also found that an overexpression of the C-terminal fragment of CX3CL1 can reduce amyloid deposition and neuron loss in mice with Alzheimer’s disease. This is the first time it’s been shown that the C-terminal CX3CL1 can aid adult neurogenesis which directly combats the neurodegeneration of Alzheimer’s disease.

This development of knowledge underscores the role of academic researchers in eventual drug discovery, Yan says. Developing knowledge about diseases and the workings of the human body is the foundation for future drugs.

“We’re in academia. Our main focus is to understand the molecule first before we try to develop a compound,” Yan says.

If researchers or pharmaceutical companies go into drug trials without this critical understanding, they could encounter many harmful side effects. With a better understanding of the science behind the disease, such side effects could be better anticipated and even avoided.

Yan says researchers can help pharmaceutical companies develop more effective drugs by working in tandem with industry partners.

“We may not be able to compete with the pharmaceutical companies directly in some cases, but we can do something to help the companies develop better drugs,” Yan says. “And that’s what’s more important to us.”