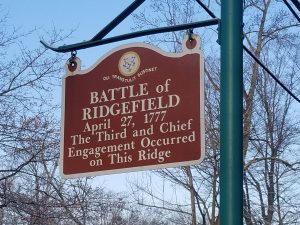

A trip to Ridgefield, nestled along the New York border, is a journey back in time, with its picture-perfect array of historic buildings, homes, and greens. And no historic event is more important to this Fairfield County town than the Battle of Ridgefield during the American Revolution in April of 1777.

The events of that battle are still evident here in town, sometimes quite literally, as with the British cannonball lodged into a corner post of the Keeler Tavern Museum on Main Street. And recently, a team of researchers from UConn assisted in a discovery that could have direct ties to that battle: the discovery of human skeletal remains that might have belonged to participants in the conflict.

Discovered when a construction company was digging into the dirt floor of a home here that dates back to the 1790s, the remains were excavated by a team that includes two UConn doctoral students and adjunct professor of anthropology Nick Bellantoni, who serves as Connecticut state archeologist and who retired from a full-time faculty position at UConn in 2014. Now, the remains will be studied and examined to try and determine whether they were casualties of the Revolutionary battle, and possibly whether they were American or British.

“Fortunately, the contractor recognized these are human and called the Ridgefield police,” says Bellantoni. “They secured the site and contacted the State Medical Examiner. The first concern in a case like this is whether this deals with a modern criminal investigation. When the medical examiners and forensic anthropologists determined these were older bones, I was contacted as the State Archeologist.”

After the discovery of the first skeleton, another was discovered about 15 feet away, and now a total of four have been found.

“The first thing we ask about human remains is if they can be left alone, but that is difficult in this case because of the construction activity,” said Bellantoni. “They would have been crushed. So, our immediate procedure was to do field excavations and have them removed in a professional and respectful way.”

Bellantoni brought UConn anthropology graduate students Megan Willison and Elic Weitzel into the effort to excavate the remains. This work is a very slow and deliberate process, which required a great deal of patience and care.

“Once we got the entire individual exposed, we photographed them and drew maps,” says Weitzel. “We took measurements of them while they were still in the ground and then very slowly began to uncover each bone using wooden and bamboo tools. Metal tools are too sharp, because they will scratch bone. After all this time, bone can be pretty degraded and weathered. We would slowly move the sediment away from the bones before removing them.”

Bellantoni compares the process to a dentist removing tartar from the teeth of a patient.

“These excavations were very difficult, one of the hardest digs I have ever had,” says Bellantoni. “These bones were laid in a very compact loam soil with pockets of clay. We needed to remove the soil in a way that was going to ensure as full a recovery as possible.

“The UConn students were just terrific. It was painstaking and took us over month, but we could not do it any quicker.”

Now that the bones have been fully removed from the ground, a multidisciplinary group of scientists from all over the country, including some at UConn, will attempt to find out as much about them as possible. A diagnostic image that produced a 3-D image will be taken of each bone.

“We would like to figure out who these people were and what their life histories were,” says Bellantoni. “We might even be lucky enough to get to the point to be able to identify some of them in terms of actual family names.”

Another help in the identification process will be the examination of about 30 clothing buttons that were discovered with the bones.

Taking place mostly on April 27, 1777, the Battle of Ridgefield involved a force of about 700 soldiers of the Continental Army and local militias fighting British troops returning from a successful raid on a patriot supply depot in Danbury. Most of the fighting occurred at a barricade in the center of town erected by American troops under the command of Gen. Benedict Arnold, who distinguished himself with his bravery during the battle. Ironically, Arnold would also be a participant in another famous Revolutionary War engagement in Connecticut, the Battle of Groton Heights in 1781 – as the leader of British forces.

During the excavation process in Ridgefield, there was always respect for the people whose bones were discovered, the researchers emphasize.

“You want to keep things as intact as possible to preserve their integrity,” says Willison.

“These are people who died and, in this case, seemingly during the Battle of Ridgefield, so we were always thinking about who they were, where they were coming from and what they were doing,” says Weitzel.

The full scientific study of the bones will take approximately one year, and it is not known exactly how much can be found out about them.

“When I got there, I knew these could be soldiers, either British or American,” says Bellantoni. “As we kept working, we really became aware of the historical significance going on. We still aren’t 100 percent sure, but with the burials being haphazard, there were no coffins, and the discovery of buttons that appear to have come from uniforms, we have a good hypothesis. These were bodies of robust young men, the bones aren’t from women and children like you would see in a family burial ground.”

As in all cases when human remains are excavated in Connecticut, there will be a reburial following the scientific investigation.

Bellantoni said that family members would be contacted if possible and if it is determined that they died in battle, the reburials would include full military honors.

“This was really a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” says Willison. “I hadn’t had any experience excavating skeleton remains before and it was wonderful opportunity to be part of it because of the history.”