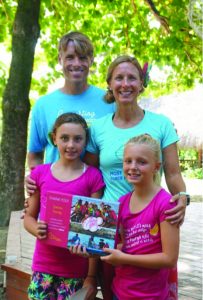

Editor’s note: Tessa L. Getchis, aquaculture extension educator and aquaculture extension specialist for Connecticut Sea Grant and UConn Extension for the last 20 years, spent last August through December in the Dominican Republic with her husband Ryan and their two school-aged daughters. While past trips to this island nation had been vacation-length recreational time, this was an extended stay with a decidedly challenging mission. She would be teaching marine science to middle-school aged girls from impoverished families, taking on some big problems while imparting hope and empowerment. The University of Connecticut and Connecticut Sea Grant supported her project there, and this story was originally published in the Spring-Summer 2020 issue of Wrack Lines, the magazine of the Connecticut Sea Grant College Program, located at UConn Avery Point.

This past fall I had the incredible opportunity to move my family to a Caribbean island, take on a new job as a middle school marine science teacher and be part of an organization that’s cultivating future female leaders in environmental activism.

My family has been traveling to the north shore of the Dominican Republic for more than a decade. This country, which shares the Caribbean island of Hispaniola with its neighbor Haiti, is a place of unimaginable beauty. Palm trees sway over wind-swept beaches, coral reefs span turquoise waters, waterfalls tumble over jagged green mountains and narrow streams meander through grasslands. Its diverse landscapes make it perfect for ecotourism including hiking, diving, surfing, windsurfing, whale watching and more.

Life is also a lot slower. (It’s a stark contrast to living here in the Northeast.) Dominicans are known for their friendly nature, and always greet you with a smile. When they say hello and ask about your day, they really want to know!

We immediately fell in love with the country and its people, but while we were enjoying the sand and sun, we realized they have been dealing with some serious challenges. Most people in this part of the Dominican Republic live in poverty, without sufficient food or clean drinking water.

They lack access to a quality education and some children are forced to sell items on the street or beg for money to support their families. The majority of children attend public schools that are only offered for a half day, and fewer than 20 percent of girls make it past the eighth grade. A rapidly changing climate with extreme flooding followed by drought, and relentlessly rising seas further threaten their personal safety and food and water security.

And then there is the garbage. The country is grappling with the amount of trash, especially plastic, entering its waterways and the looming threat of the microscopic pieces that it will continue to break into for hundreds of years. This plastic problem is so particularly grave here that a documentary Isla de Plastico (Cacique Films, 2019) was recently produced to draw attention to the widespread impacts.

It is still paradise – just paradise threatened.

It was difficult to witness such adversity in the midst of what for us was paradise (and what we considered our second “home”). As my husband and I thought about how difficult it would be if our two young daughters had to grow up in these conditions, our hearts sank. They’ve never had an empty belly. They drink from a faucet, never thinking that there might be a limited supply or that the water could make them sick. Our biggest trash problem is when collection day falls on a holiday and we have to store bags in the garage for one extra day. We felt motivated to do something to contribute, but these were huge problems and we were just visitors.

On a recent family trip we visited the Mariposa DR Foundation Center for Girls (www.mariposadrfoundation. org). We learned about the school’s mission to end generational poverty through education and empowerment. It was then we started on the path to finding our unique way to help.

Mariposa — the Spanish word for butterfly — is located in the small, rural community of Cabarete. Mariposa’s focus is on experiential learning and includes traditional classes like math and reading, as well as arts and culture, health and wellness and environmental education and activism. The center was established 10 years ago, and in addition to these classes, provides two meals a day to nearly 130 girls from ages eight to 18.

Mariposa draws its students from three nearby villages, and the girls chosen to attend for free come from families that are most in need. The neighborhoods they come from are lively with people laughing, dancing to Bachata — the country’s unique style of music — and playing dominoes. At a quick glance all might appear well, but behind the cinderblock walls the scene is much different. Many live in extremely crowded conditions, often with no bathroom or running water. They live in sweltering heat. Their homes are often exposed to flooding from land and sea, and are surrounded by litter.

We learned that the school was expanding its environmental education program. The staff wanted the students to better understand the connection between land and sea and help to inspire environmental activism. As we sat together discussing the subject, a light bulb went off. We all saw an opportunity to build a new program that would allow the Mariposas to explore, learn and love the ocean — an experience-based marine science course.

I spent months seeking out advice from science teacher friends and other experts including my colleague Diana Payne, who was a member of the team that created the first marine science education standards for the United States. They helped me to construct lesson plans and hands-on activities for each grade level that I would be teaching. A year later, after brainstorming the entire idea with family, friends and colleagues, I received approval to move forward with the program, and our family started contemplating the reality of packing all our belongings and moving to the island.

Of course there were countless nights that I sat up worrying about what I was dragging myself and my family into. We were going to spend five months in a country that we had only visited as tourists. A colleague wished me luck on our “vacation.” I knew better. I would be teaching middle school students — in another language. I would be challenging them to solve complex environmental problems. I would be asking my husband to take a pay cut from his job and to homeschool our daughters, and asking them to leave their friends, their gymnastics team and the comfort of macaroni and cheese. Would we have enough food and water, would we be safe, would my kids keep up with their education? Was I crazy for even thinking we could pull this off?

It wasn’t a small thing to pick up and leave our “normal,” but after finding a place to live, preparing our house to be rented, being trained as lifeguards and brushing up on our Spanish skills, we knew we were on the right path. I made many lists of things to do, things to buy, things to bring. Eventually I had to let go of my need to control everything and be confident that the rest of the details would fall into place. It might not be our usual brands, but my husband assured me that there would be plenty of toothpaste, deodorant and soap in the DR. Besides, it was not going to fit in our suitcases!

After saying goodbye to family, friends and neighbors, we packed our luggage full of clothes, school supplies and the one essential — sunscreen — into the van and headed to the airport. In less than four hours the plane touched down in the city of Puerta Plata with all on board cheering our arrival. As the flight attendant opened the door a wave of warm humid air rushed in and immediately calmed my nerves. Step one — arrival — complete.

Step two was orientation for my new job. I was introduced to my teaching colleagues, my classroom (a large grass covered hut called the “bohio”), my students (45 girls ranging from ages 10 to 14) and my schedule (four theory classes, four field classes and lunch duty). The theory classes would focus on the basics of marine science – water, wind, waves, weather, plants and animals. The field classes would be where the action was, involving beachcombing and watersports such as swimming, snorkeling and stand-up paddle boarding.

Though we had originally planned to enroll our daughters in an international school, we ultimately decided to keep them with us during the school day. Their teachers and principals were confident that as long as they kept up on their reading and math skills, the benefits of this trip would clearly outweigh any catching up they needed to do upon their return. So, on the first day of school all four of us headed out the door and into the unknown.

School began at 8 a.m. with breakfast and opening circle, where we received our welcome and daily news. Immediately after, everyone made their way to their separate classes. Our daughters joined classes with other girls their age learning math, reading, sewing, singing and swimming – all in Spanish. Each day after my theory classes, I jumped in the guagua (the local bus) with Diego (a Spanish teacher from Colorado), Tony and Alex (two local surfers who knew a lot about the local ocean conditions), my husband Ryan (who served as our lifeguard and Mariposa’s handyman) and our class of Mariposas to explore a new part of the coast.

We had the extraordinary opportunity to share a lot of “firsts” with our students, many of whom had little or no experience on the water. We swam and snorkeled in the open ocean, paddled in beautiful rivers and lagoons, and took long hikes to caves. Before the “fun” began, we spent time on the mandatory garbage collection that was part of our class. And we collected lots and lots of garbage. We scoured rivers, beaches and neighborhoods, making note of the type of trash — soda bottles, lollipop sticks, plastic utensils, flip flops, shopping bags, cigarette butts, rope, tiny bits of foam containers — and estimated the weight of what we had collected.

Each trip, we reminded our students that they were examples for their friends, siblings, parents and their community. Our message seemed to fall on deaf ears. But then came one miraculous day at the end of the semester. — Tessa L. Getchis

I thought about the amount of time I had spent writing lesson plans about the diversity of life, and the excitement I felt about sharing my knowledge with those girls. It was one of the greatest joys of my life when we took them snorkeling and they saw for the first time the beauty of the underwater world. But I felt that we could never escape the reach of the trash. Instead of focusing on the myriad of fish, invertebrates, mammals and birds, our attention was drawn to the contamination and damage caused by the garbage.

We weren’t deluded into thinking we could solve the problem. In fact, “hopeless” described our feelings at the time. Garbage disregarded boundaries. The trash swept aimlessly over the land, poured out of the rivers and crept in on the rising tide. No place seemed untouched. We were just a small group of teachers with middle school girls who didn’t want to get dirty — and we had a few short months. The problem was too big, and we were too late. Or so it seemed…

Each trip, we reminded our students that they were examples for their friends, siblings, parents and their community. Our message seemed to fall on deaf ears. But then came one miraculous day at the end of the semester. From my seat in the front of the bus on the way to a field site, all I could hear was shouting. Thinking there was a problem, I hurried to the back of the bus to find one of the girls jumping and pointing out the window.

She was talking so fast, shouting, “El hombre! La basura! La basura!…” that I couldn’t keep up with the translation in my head. Eventually I calmed her to the point that I could understand. She noticed a man collecting trash on the side of the road. But he wasn’t just any man. He was the same man that weeks ago had seen her collecting trash and questioned why she would ever bother. She had repeated to him the words that we had said to her each week, “I am an example for my community — I’m trying to make a difference.”

And just like that, she had lived up to the school’s motto “I am the world’s most powerful force for change.”

Now, back at home in Connecticut, inspired by our time with the Mariposas, my family and I have a new perspective on life. We are more conscientious about our choices. We are conserving water and reducing food waste, we are walking more and driving less. We have a new relationship with plastic. Even more important, we’re now having family conversations, school conversations and community conversations about how we reduce our impact on this planet. That feels good. We are still speaking Spanish, and learning how valuable knowing another language is in this increasingly diverse place we call home.

The Mariposas didn’t solve any big environmental problems by collecting garbage. Picking it up was just the conversation-starter. They grappled with all of the typical questions: “Why should I clean up someone else’s trash?” “Why isn’t anyone else helping us?” “How will we ever make a difference?” They, like us, needed to understand the complexity of the problem.

Ultimately, some good came from having been frustrated, tired, and hopeless. Because then we had to find hope, by making it ourselves. Why give up, when we have the power to make changes, see changes — even small ones — in the communities we love?

Excerpts from the Getchis Family Blog

Tessa Getchis and her family shared their experiences in a weekly blog over their five-month stay. Below are some samples:

Sept. 11: “We have been given this amazing opportunity…For some of the (students) it will be their first opportunity to step foot in salt water.”

Sept. 18: “This week we took the girls on their first field trip to the Yasica, a freshwater river that leads to the Atlantic Ocean…This first week was all about exploring nature and getting comfortable in the water. It wasn’t without challenges, but there were many smiles and memories made.”

Oct. 2: “Estoy emocionada por…” (I’m excited for) was the prompt for our first class this week…they were excited to get out on the water, and also to learn about marine biology. They were also fearful of sharks, eels, crocodiles and urchins.”

Oct. 9: “This week the Mariposas learned how to use a standup paddle board…Diego and Ryan gave the girls some tips and then we were off to explore the reef. The girls were met by a myriad of fish and invertebrates in every color of the rainbow.”

Nov. 17: “While I’m concerned about the future that lies ahead for these girls, I still have a great deal of hope. They are paying attention, asking questions and challenging the status quo. They are thoughtful and creative and we just need to give them the tools and resources they need to succeed.”

Nov. 20: “We walked along trails through the lush green forest, along lagoons and to hidden caves. The girls shied away from the ice-cold waters but the air thick with mosquitoes was enough to make them jump in. They laughed and played and splashed, and yelled each time they saw a fish… It was a pleasure to see kids just enjoying being kids.”

Nov. 27: “Last week in class we learned about marine mammals, and so the girls were thrilled when we came across a small pod of dolphins on our open water (snorkeling) excursions this week.”

Dec. 16: “I am feeling so very grateful for this adventure. So many dreams have been fulfilled. We experienced more depth in the beauty, diversity and culture of this country and its people. I started a new job as a marine biology teacher. I was lucky enough to have lots of help from Ryan Getchis…”