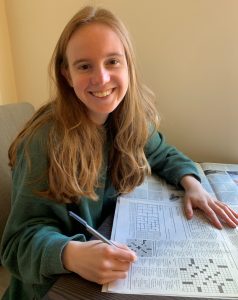

The end of August was quite eventful for Anne Marie Crinnion: she started her doctoral studies in psychological sciences at UConn, and a crossword puzzle she wrote appeared in The New York Times for the first time.

Crinnion, who is studying remotely this semester from her home in Villanova, Pa., started solving crossword puzzles towards the end of high school and began doing the famously challenging Times crossword on daily basis as undergraduate at Harvard.

“A few years ago, I had the idea of making a little puzzle for my boyfriend as a gift,” says Crinnion. “It wasn’t really a true crossword puzzle, as it wasn’t formatted nicely or have the rules in place for a New York Times puzzle. Making that got both of us interested, and we found out it is actually something fun to do. From there, we created a good word list and ranked words and got a computer program that makes the formatting a lot easier. I started to think about fun ways that words connect and that leads to a fun theme idea, which leads to an interesting puzzle.”

The Times crossword puzzle is the gold standard in the intensively competitive crossword world and receives hundreds of submissions a week, for only seven spots.

“The odds are against you,” says Crinnion, who has also had a puzzle appear in The Wall Street Journal and is currently working on one for The Atlantic. From the time Crinnion submitted the puzzle to the time it was published took about nine months, although she found out three months ago it had been accepted.

Crinnion’s puzzle appeared on Monday, Aug. 31 and had the revealer answer of “CHANGING LANES.”

“Monday through Thursday puzzles generally have a theme, which is typically the style that I construct,” says Crinnion. “A theme usually consists of four to five answers in the grid that are longer words and phrases that somehow are connected in an interesting way. In recent years, the themes have gotten incredibly creative.”

Crinnion’s theme words all had homophones to streets and roads, such as Olympic gymnast “Aly” Raisman, and “rode” horseback.

The puzzles can take Crinnion anywhere from ten to 40 hours to complete.

“I often work on it in small chunks over multiple days, but sometimes I get super excited and have a very clear idea and it does not take that long,” says Crinnion.

The art of putting a puzzle together starts with a 15-by-15 blank grid for Crinnion, and creating the long answers.

“If you have long answers overlapping each other, it is very difficult to fill in with actual words,” says Crinnion. “You have to create space between them and put black squares in to break them up. You want to create enough space to separate the theme answers and leave some room for fun, bonus long answers. I have a word list that is ranked and that helps fill in the other various spots. The software will suggest what word can actually fit in the puzzle. You need a word with an ‘e’ in the second slot and a ‘w’ in the sixth spot, or something like that, and it will tell you all the possibilities.”

The clues are not written until all the words in the puzzle are done, and they are often edited by the publication.

“The clues are not something I feel too married to,” says Crinnion. “I know a lot of them will probably be changed based on what day the puzzle is going to run and the audience. It’s fun when you write a creative one and it makes it through. It is more about the grid, the theme, and how clean it is. That is what makes the puzzle stand out and eventually get published.”

Her academic program at UConn will take about five years and focuses on language and cognition. It has started with classroom work, but will be research-centered.

“I am interested in how people communicate, and how we communicate so easily even when we are listening to lots of different people talk,” she says. “There’s really so much variability that is present in spoken language, yet for the most part people generally have a pretty easy time using language, and I am interested most deeply in underlying properties that allow people to recognize a word in a variety of contexts. I am interested in properties of speech perception, and what is making up the acoustic signal we are processing. I am also interested in understanding how spoken words are actually recognized as a word that has meaning and connects to other words in a given context.”

Crinnion plans to continue to construct more crossword puzzles as her schedule allows.

“I love language, love words, and love thinking about how different words connect in interesting ways,” she says. “I think it’s related to my research. I’ve always been fascinated by language and communication.”